The U.S. Army has manufactured a bullet that can change direction mid-flight, according to a story reported in the Independent (U.K.).

Known as the Extreme Accuracy Tasked Ordnance (EXACTO), the technologically advanced rounds are manufactured by Teledyne Technologies and paid for by DARPA, the research and development arm of the Defense Department.

A video of a demonstration of the bullet is found on the Independent website and shows the round being fired twice, the second time the target is intentionally missed, but the bullet compensates for the error and finds the mark.

While the interested parties have revealed very little about the science behind the bullet, The New American reported in August 2012 that most of the tests were being performed at Sandia National Laboratories. A report released earlier in 2012 revealed that the scientists had engineered a prototype that was effective at a distance of up to two kilometers.

According to a story about the bullet in Wired:

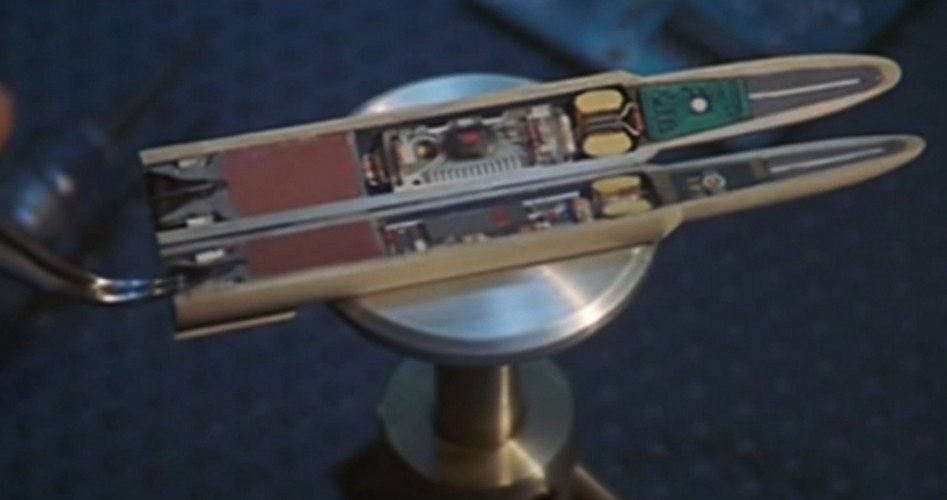

Each self-guided bullet is around 4 inches in length. At the tip is an optical sensor, that can detect a laser beam being shone on a far-off target. Actuators inside the bullet get intel from the bullet’s sensor, and then “steer tiny fins that guide the bullet to the target.” The bullet can self-correct its navigational path 30 times a second, all while flying more than twice the speed of sound.

The story published by the Independent on December 17, 2014, reported on the likely mechanism that makes the EXACTO magical:

The companies involved have not disclosed how the bullet works, but it is thought to have small fins that re-direct its path. The sniper shines a laser at the target, which the bullet then follows as it moves through the air.

That stops the complicated adjustments that snipers have to make for wind, weather, the dip of the bullet as it flies through the air and any movement by the target, and could mean that snipers’ targets could be hit from much further away.

Tech Times zeroed in closer on the precise workings of the technology:

With accuracy standards that it was able to achieve even at a distance of 1.2 miles, the self-guiding bullet works by using optical sensors that are found on the surface of its nose. These sensors are capable of gathering in-flight information which is then transmitted to the bullet’s internal electronic systems. After the data is interpreted by the latter, it is then used to adjust a number of fins that are nestled along the exterior of the bullet, making the bullet change its direction.

As the technology facilitating the expansion of the surveillance state becomes more advanced, the need for proximity to the target of the surveillance diminishes. For example, very soon drones will be equipped with lasers that can penetrate walls, map the interior of a home or other building, and scan a targeted individual’s genetic code from 50 yards with dizzying speed and accuracy. Additionally, the ability to keep drones perpetually airborne is being engineered, thanks to multi-million dollar research and development grants offered by the Pentagon to companies on the edge of technological advancement.

One such grant was awarded by DARPA to a company tasked with reducing the size and increasing the power of laser-based optics used by snipers. In 2012, DARPA awarded Cubic Corporation $6 million to develop a “laser-emitting targeting computer” for American military snipers. According to a story in Wired, the “goal is to reduce the number of calculations the sniper and his teammate — a spotter — have to do before they can make an accurate shot.”

The government wants the device not only to have pinpoint accuracy, but to be small enough to fit on the sniper’s weapon, eliminating the need for the spotter altogether and enabling the shooter to identify and kill the target from heretofore impossible distances.

Cubic Corporation is accustomed to making historic strides in distance-measuring devices. The company’s website boasts that in the 1960s its engineers created “Electrotape Distance Measuring Instrument — the world’s first commercial distance surveying system to provide centimeter accuracy from 100 meters to 50 kilometers.”

As laudable as that is, the company has allegedly delivered something much more impressive. This über-powerful scope is called appropriately the One Shot XG. Although Cubic Corporation has not specifically described their product, DARPA’s request for proposals mandates that the instrument be a “compact observation, measurement, and ballistic calculation system” that will allow the sniper to make kill shots “under crosswind conditions, at the maximum effective range of current and future weapons.”

If their contracts were fulfilled on time, DARPA likely recently took delivery of a scope capable of calculating “crosswind profile, direction, range, temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, cant and pointing angles, etc.” as close to real time as possible and then instantly delivering that data to the sights of the gun and a display screen viewed by the sniper. And, it must be capable of doing all of this in the dark. The device must also have a range of two kilometers (1.24 miles) and must have a first round hit probability of 60-90 percent at that range.

In previous phases of the One Shot XG program, the lasers used by the scope were overheating and the effective first round kill range was reduced to 300 meters “under starlight conditions.” Also, battery life was unacceptably short (less than 20 minutes), the instrument was too heavy (4 kg, as opposed to the .66 kg required by the Pentagon), and the readings were washed out in direct sunlight.

Self-guided bullets that hit a target over a mile away and scopes that can home in on a target from that same distance are just the type of small, light, and lethal weaponry that are perfectly suited to be attached to drones deployed for the purpose of finding and destroying anyone suspected of posing a threat to the homeland.

Perhaps the most frightening implication of this is that all of this remote delivery of death can be done with very limited human participation. It is this “video game” culture of long-distance, impersonal killing that has reportedly led to the mental trauma suffered by so many of those whose hands pull the trigger on the drone joystick or the long-range rifles. This may be the reasons a study published in 2013 and reported in the New York Times found that “pilots of drone aircraft experience mental health problems like depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress at the same rate as pilots of manned aircraft.”

What is indisputable, though, is that too much of this technology is being used to dispense with due process and surrender to the president and his cabal the power to kill their enemies, foment popular support for never-ending wars, and accumulate unbounded control over life and death that would make even Caligula blush.

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American. Follow him on Twitter @TNAJoeWolverton.