Local police all over the country are using highly sophisticated, very expensive surveillance tools to capture information from cell tower traffic from the innocent and the guilty alike. The devices they use were originally touted as “tools for combating terrorism.” Now they are being used as the shortest path in solving even the most petty crimes.

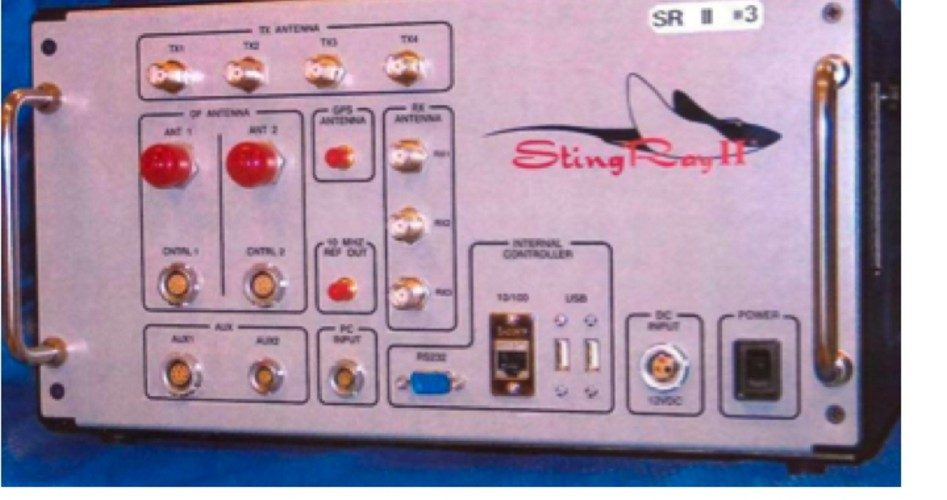

USA Today is reporting that cell-site simulators, known as “Stingrays” are being used at an increasingly alarming rate to capture information about all mobile phones within the area where the device is being used. There are obvious issues with the use of these devices as it relates to privacy. The Stingray does not target particular phones, but instead vacuums up all data from all phones in the radius of the coverage of the device. That means that even if police were using it in the most extreme situations — say to track a kidnapper or known terrorist — there would still be legitimate privacy concerns.

Those concerns are amplified by the fact that police use Stingrays for everything from serious crimes, such as those mentioned above, to petty crimes such as simple burglary and prank phone calls. Police are using these devices as the shortest path because it is easier than conducting an old-fashioned investigation. The result is that police are becoming accustomed to the ease and convenience of these tools and are using them more and more. The city of Baltimore alone has used its Stingray 4,300 times since 2007. That is at least 11 times per week. The majority of those cases were for petty crimes.

If Baltimore is any indication of the frequency with which police across the country are using these tools, the problem is gargantuan. More than 50 police departments have and use Stingrays. It is certain that other departments are overusing these surveillance tools. Often there is no search warrant obtained for their use — a direct violation of the Fourth Amendment’s guarantee of freedom from “unreasonable searches and seizures” and the requirement that police have “probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation” to obtain a warrant which must “particularly [describe] the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Joel Hruska wrote in his piece for extremetech.com:

Police often fail to submit a warrant request — one police department in Florida has admitted to using a stingray more than 200 times since 2010 without ever getting a warrant for its use. These devices are indiscriminate — in rare cases, such as a stolen cell phone, police may know in advance precisely which device to target, but in the majority of scenarios they’re fishing for bait to see what they can find.

The Stingray — which is about the size of a large suitcase — is transported in either a surveillance van or a police car. It acts as a “man-in-the-middle” by mimicking a cell tower and fooling any mobile phone in the area into connecting to it. It then harvests info from the phone including the number of the phone, the number the phone is calling or texting, the location of the phone, and information about the phone itself. Once the Stingray has that information, it relays the connection to the nearest real tower in the area. The only things that might alert a mobile phone user to the “man-in-middle” attack by a Stingray would be a sudden dip in battery power or a slight delay in network speeds. The Stingray sends a command to the phone to increase antennae power to maximum, and it takes an extra bit of time to grab what it wants and forward the connection to a real tower.

USA Today interviewed one officer in Baltimore about the use of these devices and their effectiveness. He said the Stingrays help solve cases. “We’re out riding around every day,” said one officer assigned to the surveillance unit, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the department’s non-disclosure agreement with the FBI. “We grab a lot of people, and we close a lot of cases.”

But the reality is that there is more to the story than that.

While the use of Stingrays does bring about arrests, many of the cases are dropped or reduced to get a conviction on lesser charges in exchange for a confession. Why is that? Because police departments have to sign non-disclosure agreements with the FBI to even obtain or use Stingrays. As a result, police often do not — cannot — disclose (even to prosecutors) that they used the device. This means that police are caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to testifying in court. If the officer discloses the fact that the reason he knew where to find the suspect was that he used a Stingray to sniff out his phone, the officer could be liable for violating the non-disclosure agreement. If he testifies falsely, he would be guilty of perjury. So the case is either dropped or the charges are reduced.

One example of this was highlighted in the article and shows the futility of relying on these devices.

Prosecutors have certainly agreed to forgo evidence officers gathered after using a stingray. At a court hearing in November, a lawyer for a robbery suspect pressed one of the detectives assigned to the surveillance team, for information about how the police had found a phone and gun prosecutors wanted to use as evidence against his client. Haley refused to explain, citing the non-disclosure agreement. “You don’t have a non-disclosure agreement with the court,” Judge replied and threatened to hold the detective in contempt if he did not answer.

Prosecutors quickly agreed to forgo the evidence rather than let the questioning continue. “I don’t think Det. Haley wants to see a cell today,” Assistant State’s Attorney Patrick Seidel said.

The lesson many defendants and lawyers will take away from this is to press that same question in their cases. The likelihood is great that if such a device was used at all, the case will disintegrate.

The electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) — an organization dedicated to preserving digital liberty — has been working for years to expose the use of these surveillance tools. EFF lawyer Hanni Fakhoury said, “The problem is you can’t have it both ways. You can’t have it be some super-secret national security terrorist finder and then use it to solve petty crimes.”

EFF has launched a fairly aggressive campaign against all “street-level surveillance.” The Street-Level Surveillance Project (SLS) encourages citizens to hold police accountable and provides tools to do just that. EFF lists Stingrays, automatic license plate readers, biometrics, and other technologies used by police which threaten privacy and liberty.

Their website says:

The SLS Project addresses an information gap that has developed as law enforcement agencies deploy sophisticated technology products that are supposed to target criminals but that in fact scoop up private information about millions of ordinary, law-abiding citizens who aren’t suspected of committing crimes. Government agencies are less than forthcoming about how they use these tools, which are becoming more and more sophisticated every year, and often hide the facts about their use from the public.

Hopefully, as more cases fall apart because of questions about the use of Stingrays, and as the public becomes more aware, their use will fall out of favor, and police will get back to conducting investigations the way they used to. Citizens need to demand it.