The Birth of Western Christendom

On a fine spring day in April in the year 799, a colorful procession wound its way through the streets of Rome in honor of the Greater Litanies, the major rogation day in honor of all the saints. The procession included many dignitaries of the Holy See, including the pope himself, Leo III, who had risen from humble origins to become pope less than four years earlier, succeeding the aristocratic Adrian I. In his short pontificate, Leo had already made a powerful friend in the Frankish king Charlemagne, who had sent him a large trove of gold and a number of envoys, or missi dominici, who functioned as a papal protection detail. Besides his powerful Frankish ally, however, Leo also had powerful enemies. Most of them were supporters and relatives of his late predecessor, who regarded Leo as too common a man for the job, and wanted him replaced with one of their own.

And on April 25, 799, as Leo III and the joyous procession neared Rome’s Flaminian Gate, the pope’s enemies struck. A large group of armed men attacked the pontiff, intending to blind him and rip out his tongue; a man so incapacitated would not be eligible any longer for the office. In the fracas, the assailants nearly succeeded, possibly managing to partly blind the 49-year-old pope, and certainly injuring him severely. But before they could finish the task, two of Charlemagne’s envoys charged into the fray and managed to rescue Leo from further injury. One of the envoys, Duke Winigis of Spoleto, spirited the pope out of Rome for protection, and later ensured his safe passage to the German town of Paderborn, where Charlemagne himself was encamped. The Frankish ruler received the pope into his camp with great honor, and the already powerful friendship between the two men was further reinforced. No one at the time could have foreseen that this incident would lead to an event on a long-ago Christmas Day that is now regarded as the birth of Western Christian civilization, and would ensure that Charlemagne would be remembered as the “father of Europe.”

The Rise of the Franks

The rise of Charlemagne, and his alliance with the pope, represented a concentration of power not seen in Western Europe for more than three centuries. The failing Western Roman Empire had crumbled in the years after the titanic Battle of the Catalaunian Fields of 451 (in what is now northeastern France), where the disciplined valor of the Roman general Aetius had saved the West from annihilation by a vast barbarian alliance led by Attila and his army of Huns. In that battle, the leader of Rome’s chief ally, the Gothic king Theodoric, had fallen along with hundreds of thousands of others, a final debilitating event that left the remnant Western Empire nearly bereft of military and political leadership. Aetius himself was murdered two years later by a feckless and ungrateful emperor Valentinian III, the last Western Roman emperor of any consequence. One of the men enlisted by Valentinian to carry out the murder, Petronius Maximus, then turned on the emperor himself, killing him and earning a couple of months as emperor over a pathetic and moribund dominion. By the time the last Roman emperor of the West, Romulus Augustulus, was removed by the Germanic opportunist Odoacer, the glories of Rome were only a dim memory, and her capital city mostly deserted.

These events in the second half of the fifth century had ushered in an era of relative barbarism in Western Christendom, in which the security of centuries of Roman rule was replaced by warring states controlled by Franks, Visigoths, Lombards, and other successor peoples. The most consequential of these early post-Roman states, the kingdom of the Franks, was ruled over by Clovis I, who took the throne in 481, only five years after the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Clovis, usually reckoned the first ruler of what would become France, was the founder of the Merovingian Dynasty and the first to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one rule. Moreover, Clovis, under the encouragement of his wife, Clotilde, eventually embraced Nicene Christianity and was baptized on Christmas Day 508. This act led to the mass conversion to Catholicism across France, the Low Countries, and Germany, creating a new religious unity among the fledgling nations of continental Western Europe, and laying the foundation for the close relationship between Charlemagne and the Holy See centuries later.

The Merovingian Dynasty, the first French royal line, weakened with the passage of time, and proved wholly inadequate, in the early eighth century, to the defense of France against a bold and terrifying new power, Islamic conquerors from Africa. By that time, the office of king had become largely ceremonial for the Merovingians, with most of the real power wielded by administrators known as mayors of the palace (maior domus). One of these, the energetic Charles Martel (whose surname meant “hammer”), acted as regent for years after the death of king Theuderic IV in 737.

Like many other Germanic peoples, the Franks under the Merovingians had an instinctive aversion to centralized government power, a reaction in part, perhaps, to centuries of Roman centralized oppression. But in the crisis of the Islamic conquest, the French were in need of resolute leadership and unity, and Martel furnished both. As with most of Western Europe during the early Dark Ages, the Franks had no professional military, so Martel, having warned the pope of the existential threat posed by the Moors, managed to secure a large loan from the papacy, which he used to recruit, equip, and train a large professional fighting force. In October of 732, the seemingly irresistible hosts of the Ummayad Caliphate, which had already subdued most of Visigothic Spain, met Martel’s seasoned Frankish army at the Battle of Tours in central France. Despite lacking a heavy cavalry force and being significantly outnumbered, the Franks, under the leadership of the canny military tactician Martel and his ally Odo, the duke of Aquitaine, routed the Moorish army, inflicting at least 12 times as many Moorish deaths as Frankish, including the enemy commander Al-Ghafiki, the governor of Moorish Spain. The Battle of Tours prevented the Moorish host from reaching Tours, Paris, or elsewhere in northwestern Europe. The decisive victory turned back the tide of Islamic expansion in Western Europe and established Martel as a national hero, preparing the conditions for him and his descendants to claim the French throne.

Turning back the tide: At the Battle of Tours, which represented the high-water mark of Muslim incursions into France, Charles Martel’s outnumbered and underequipped army inflicted a crippling defeat on the Moors, killing their leaders and routing their formidable cavalry. This defeat insured that France and northwestern Europe would remain Christian. (Wikimedia Commons/Charles de Steuben)

Martel’s son Pepin the Short ultimately deposed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, after securing papal approval. Childeric was removed without violence and consigned to a monastery, while Pepin was elected the new king of the Franks by the Frankish nobles, and was later anointed by Pope Stephen II, who traveled all the way to Paris in 754 and also proclaimed Pepin patrician of the Romans. This new title made Pepin and his heirs official defenders of the church at Rome, a role that both Pepin and his pious descendants, including his son Charlemagne, took seriously.

The man who became Charlemagne was Pepin’s older son Charles, who was 12 when the pope anointed his father king and protector of the church. Because of the uncertainty of human lifespans in those days, the pope took the opportunity of anointing both Charles and his three-year-old brother, Carloman, in the expectation that one of them would eventually inherit Pepin’s scepter.

That occasion came in 768 with the death of Pepin. In a general assembly, the Franks elected Charlemagne and Carloman joint monarchs over Pepin’s dominions, and partitioned the realm between them. By this time, Charlemagne was in his mid-20s and had been involved in military campaigns with his father for years, whereas Carloman was still a callow youth of 17. The two did not get along, and before long, the animosity led to open conflict. The Aquitaine revolted against Carolingian rule upon Pepin’s death, and his two heirs, whose inheritances both included parts of the rebellious region, could not agree on how to suppress the uprising. Over the next three years, relations between the two continued to deteriorate until, suddenly and conveniently, Carloman died in 771 of unknown causes. Whether Charlemagne himself was involved in his rival sibling’s untimely death has never been established, and does not seem to have been alleged at the time. Whatever the cause of Carloman’s demise, it cleared the way for Charlemagne to become, like his father, the undisputed ruler of all Franks.

Imperial Expansion

One of Charlemagne’s first challenges as sole ruler of the Franks involved Desiderius, king of the Lombards and Charlemagne’s former father-in-law. Charlemagne had married Desiderata, the first of his four wives, in 770, only to annul the marriage the following year. The annulment enraged Desiderius, who began scheming with Carloman to depose Charlemagne, but before any plans could come to fruition, Carloman died. Still seething, Desiderius, knowing of Charlemagne’s piety and close ties with the papacy, vented his anger on the new pope, Adrian I, beginning in 772. The Lombard king invaded and annexed certain papal dominions and made it clear he intended eventually to march on Rome itself. The pope sent an urgent request for help to Charlemagne, who promptly marched down to Italy, defeated the Lombards, and removed Desiderius from power, consigning him to a monastery. With the defeat and deposition of the last Lombard king, Charlemagne became master of most of northern Italy — excluding, of course, the papal domains, which he duly restored to Adrian I. The latter, in turn, granted Charlemagne the title of patrician over his new Italian territories.

Next, Charlemagne turned his attention to the Muslim power that ruled Spain. Although Charlemagne’s father and grandfather had turned back the tide of Islamic conquest in France and driven the Moors south of the Pyrenees, the threat continued, especially considering the potential for an alliance between the Moors and Aquitaine, the domain of the people known as Basques, who still ached to throw off the Carolingian yoke. As a result, when Charlemagne, along with a coalition of Lombards, Burgundians, and others, launched a massive invasion of northern Spain in 778, he did so with a wary eye for Aquitanian treachery. Despite a lengthy battle and siege, Charlemagne was unable to take the key northern Spanish city of Zaragoza, and ultimately decided to return north of the Pyrenees rather than risk an Aquitanian uprising on his rear. But as his forces marched back across the Pyrenees, through cold, windswept Roncesvalles Pass, Charlemagne’s worst fears were realized. They were ambushed by a large Aquitanian force and much of the flower of Charlemagne’s military leadership was killed in the rout. Among the dead was the celebrated warden Roland, whose heroism inspired The Song of Roland, the first major piece of literature in the French language.

Despite the setback, Charlemagne’s forces continued the campaign to establish a more extensive buffer zone, called the Spanish March, in northern Spain. By the late 790s, they had captured Barcelona, and by the early 800s had extended their conquests past Tarragona and all the way to the mouth of the Ebro River. In this way, much of Catalonia and part of Aragon were permanently reunited with the Christian West.

Charlemagne also engaged in almost continuous expansion eastward into various German states, destroying pagan shrines and imposing Christianity wherever he went. Over the two decades from 777 to 797, he brought Saxony under Frankish rule, while during the 780s, his forces also subjugated Bavaria and Carinthia. The final submission of these regions involved the total renunciation of paganism and the unconditional acceptance of Christian sacraments and doctrines. Even many Slavic nations and the once-formidable Avars of Eastern Europe became tributaries and allies of Charlemagne’s Frankish empire.

In the space of three decades, Charlemagne had built the already-formidable Frankish state into a bona fide Christian empire that spanned most of Western and central Europe, at least the peer of the Byzantine Empire and its glittering capital, Constantinople, in Eastern Europe and Asia Minor. Not only that, the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman, Empire, while itself a bastion of post-Roman Christian civilization, had fallen out of favor in Western Europe, owing in large measure to Constantinople’s fraught relationship with the papacy. While the great schism between Western Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity still lay in the future, the theological and cultural differences between Eastern and Western Christendom had already become pronounced. For one thing, the Byzantines, while claiming to be the legitimate successors of the Roman empire, had developed a completely different culture from that of Rome and of Western Europe, one that was more conspicuously Greek than Italian and that often looked eastward for its inspiration. Having to contend with a more or less constant existential threat from eastern invaders such as the Avars, Pechenegs, Bulgars, and various Muslim powers, Byzantium had developed a predilection for negotiation and appeasement of aggressive enemies rather than precipitous military confrontation, a posture that has prompted historians over the centuries, including Gibbon, to accuse them of oriental pusillanimity.

Moreover, among Eastern Christians the use of religious icons was controversial, along with numerous other points of doctrinal dispute. So-called iconoclasts, who sought to destroy all statues of saints, lest those praying before them be guilty of idolatry, caused consternation in Rome, as did the bitter debate over the “filioque” clause, a Latin term meaning “and the Son,” which supposedly implied that the Holy Ghost came of both Father and Son, rather than just the Father. The Byzantines opposed the former view, holding it to be a departure from the original Nicene Creed, but by Charlemagne’s time, it was widely incorporated into many Western versions of the liturgy. These and many other points of disagreement might seem trivial from a modern vantage point, but in those early centuries of Christianity, scrupulous emphasis was laid on getting the doctrine correct.

Besides all of these other differences, the Byzantine ruler at the time of the great papal crisis of 799 was a woman. Irene of Athens, wife of Emperor Leo IV, had been de facto ruler of the empire since Leo’s death in 780, and became sole de jure ruler in 797 after a power struggle with her son Constantine VI ended with the latter being taken prisoner and blinded. Irene understood well the ruthlessness of Byzantine court politics, and did not intend to be maimed, immured in a convent, or worse, by her innumerable enemies. And although Irene earned some respect in Rome for her principled opposition to the iconoclasm of her husband and others (it was reported that Leo, after finding two icons hidden under her pillow, refused to ever have marital relations with her again), her rule was largely viewed in the West as illegitimate. She was, after all, the first woman ever to lay claim to Caesar’s seat, and had strong-armed her way into power at the expense of her son, the legitimate heir. Inevitably, then, when Pope Leo III found himself on the run from a powerful and murderous conspiracy, it was not to Irene and Constantinople that he turned; it was to their equally powerful Western rivals and proven champions of the papacy, the Carolingians.

Father of Europe: As the first emperor of what came to be called the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne, thanks to his campaign of unification, Christianization, and revival of culture and learning, is rightly regarded as the originator of Western Europe’s identity as the locus of Western Christian civilization. (http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public)

Christmas Coronation

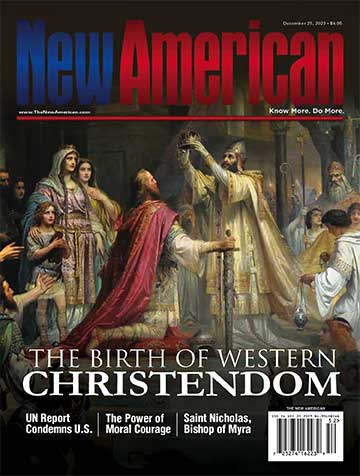

Accounts differ on what led to the momentous events of Christmas Day in the year of our Lord 800, but this much is certain: After Charlemagne and his army accompanied the wounded pope back to Rome in late 799, he set about restoring order in the church. He held a synod in November at which grievances were aired, and Pope Leo on December 23 swore an oath of innocence to the Carolingian emperor. Two days later, Charlemagne attended Christmas Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica. As he knelt at the altar to pray, the pope placed a crown upon his head and declared him emperor of the Romans — which included, of course, the Eastern Romans in Constantinople. Still debated by scholars is whether Charlemagne knew of the coronation beforehand. His biographer and longtime privy councilor Einhard insisted that the coronation was a complete surprise. Charlemagne, Einhard wrote, “so disliked [the title of emperor] at first that he affirmed that he would not have entered the church on that day — though it was the chief festival of the church — if he could have foreseen the design of the pope.”

Whether or not he had foreknowledge, Charlemagne did not refuse the crown or the title. Everyone who witnessed the event understood the far-reaching political ramifications: Leo was not only coronating his most powerful and reliable supporter, he was also repudiating the imperial pretensions of Irene and proclaiming a Christian Roman Empire reborn in the West. The coronation of Charlemagne is reckoned the starting point of the Holy Roman Empire, a unifying power in Western Europe for the next thousand years. It also marked the starting point of a unified post-Roman Christian Western European culture.

Like many ambitious, powerful people, Charlemagne was a man of mixed character traits. On the one hand, his military and political aptitude were unsurpassed in his time, and his religious faith and loyalty to the papacy were unquestionably genuine. On the other hand, his piety did not extend as consistently to matters of concupiscence; in addition to four wives, Charlemagne had numerous concubines and sired 18 children in all from seven different women, only two of whom were his spouses. He also spent much of his long reign waging wars of conquest and forced conversion to Western Christianity.

The Carolingian Renaissance

Despite being an enthusiastic patron of the arts and sciences, Charlemagne never learned to write (despite making considerable effort in his old age), and it is doubtful that he could read very well, if at all. In this last respect, he was very much a monarch of his times, when literacy was a rare and specialized skill. But Charlemagne did understand the value of culture and learning, and became medieval Western Europe’s first outstanding patron of the arts and sciences.

The roughly century-long period during and after his reign, from the late eighth century through the late ninth century, is known as the Carolingian Renaissance, the first — but not the last — attempt by Europeans to recreate the splendor of Rome in its apogee. Charlemagne himself sought out the most talented scholars available and invited them to his court. The most outstanding was the polymath Alcuin of York — “the most learned man anywhere to be found,” according to Einhard — who, along with other scholars drawn not only from Charlemagne’s realm but also from the British Isles, labored to build up a palace school and a broader system of church schools tasked with instructing generations of pupils in the trivium (logic, grammar, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium (astronomy, music, arithmetic, and geometry) lifted from classical Greco-Roman curricula.

For the first time since the demise of the Classical civilization, art flourished in the West, mostly using styles inspired by Rome. The surviving sculpture, frescoes, metalwork, and mosaics of the period are few, but they clearly inspired the great Romanesque and Gothic aesthetic modes of later centuries.

Mired for centuries at the subsistence level, the economy of Western and central Europe also increased dramatically during this period, with surpluses of grain and other commodities being produced for the first time in many generations. Larger commercial towns and sophisticated trading networks appeared, and the construction of new buildings (especially churches), bridges, and roads proliferated. It has been estimated that between the late 700s and the mid 800s alone, 27 new cathedrals, 100 royal residences, and more than 400 new monasteries were constructed, in the imitative Classical or proto-Romanesque style favored by the Carolingians.

It was demonstrably during this same period that the notion of Europe as a distinct and more or less unified cultural area, in addition to a geographical region, first gained currency. Although significant portions of Europe had fallen, and would yet fall, under the sway of Islam, and although many regions, especially in the remote north, remained pagan, the unifying idea of Europe as the continent of Christendom appears to have been a product of the Carolingian era, and has persisted down to the present day.

Perhaps the two greatest contributions of the Carolingian Renaissance were the creation of a convenient and easily readable new form of writing, the Carolingian minuscule, and the establishment of Medieval Latin as a language of scholarship and record-keeping. The Carolingian minuscule was a form of Roman writing that employed spaces to separate words and made use of lower-case letters, both features of which made writing and reading much easier and encouraged the spread of literacy. According to historian Philippe Wolff, “it would be no exaggeration to link [the development of the Carolingian minuscule] with that of printing itself as the two decisive steps in the growth of a civilization based on the written word.” Using this critical new scribal tool, Carolingian scholars produced at least 100,000 manuscripts during the ninth century, most of them priceless copies of works from Classical antiquity, such as the works of Cicero, Horace, and Caesar. Somewhere between 6,000 and 7,000 of these laboriously copied tomes still survive, and are generally the earliest extant versions of these works. Moreover, the Carolingian Renaissance marked the starting point for the long medieval enterprise of copying and re-copying these precious works; absent the Carolingians and their influence, the writings of the Classical world might have perished entirely, and names such as Cicero might be unknown to the world today.

With the establishment by the Carolingians of Medieval Latin, a flexible version of the Roman tongue with specific rules for adopting new vocabulary in a changing world, the Middle Ages had a scholarly, cultural, and civic lingua franca in which laws could be promulgated, records kept, and new works of theology, science, philosophy, and literature produced and circulated internationally.

High honor: The gold and silver sarcophagus of Charlemagne, known as the Karlsschrein, or “Shrine of Charles,” at Aachen Cathedral. (Wikimedia Commons/ACBahn)

It is thus not hyperbole to assign to the Carolingian Renaissance the origin of Western Christian civilization as a coherent force, one that both sought to revive the glories of the Classical past and aspired to greater heights as a result of the amplifying power of Christian civilization, which the Greco-Romans had lacked. Wrote the far-seeing Alcuin to Charlemagne:

If many are infected by your aims, a new Athens will be created in France, nay, an Athens finer than the old, for ours, ennobled by the teachings of Christ, will surpass all the wisdom of the Academy. The old had only the disciplines of Plato for teacher and yet inspired by the seven liberal arts it still shone with splendor; but ours will be endowed besides with the seven-fold plenitude of the Holy Ghost and will outshine all the dignity of secular wisdom.

In late 813 Charlemagne, feeling his age, summoned his sole surviving legitimate son, Louis (nicknamed “the Pious”), from his court in Aquitaine and had him crowned co-emperor. He fell ill shortly thereafter, and died in January 814. The Carolingian Renaissance continued under the rule of his son, and although it was overwhelmed by new waves of barbarian invaders — Vikings, Magyars, and others — by the end of that century, the crucial reforms achieved by the Carolingians persisted. While the young civilization was forced, under the withering assault of new waves of barbarians, to retreat into the monasteries for a time, the educational programs, writing, and production and illumination of manuscripts continued. Today Charlemagne is often known as the father of Europe, and his Christmas coronation as the first day of a unified Christian West, the first great illuminating event to pierce the darkness of the fallen and benighted realms of the former Roman Empire, and the precursor of later renaissances and awakenings that, over the many centuries since, have conferred upon us Western Christian civilization in its fulness.