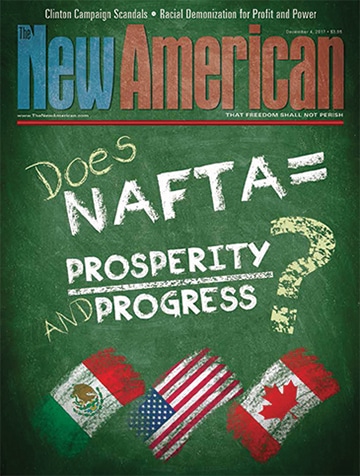

Does NAFTA Equal Prosperity and Progress?

NAFTA: Bill Clinton promised “jobs, American jobs, and good-paying American jobs.” Ross Perot warned of a “giant sucking sound” as those American jobs would head south of the border in search of lower wages. Donald Trump campaigned on the claim that NAFTA was a “disaster” and that Mexico was “ripping us off.” So what’s the truth, nearly 24 years after the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect?

Some say NAFTA has been good for our economy. But tell that to automotive-industry workers who saw their plants move to Mexico. Mexico, since the implementation of NAFTA, has become an auto-manufacturing hub. The “Big Three” Detroit automakers (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) have all moved production facilities to Mexico, where they pay workers less than a tenth (typically $1-$3 per hour, with no benefits) of what they’d be paid in America.

Or how about those Hershey’s chocolate bars that tempt you in the grocery store? Those are made in Mexico now, too, after Hershey’s closed plants in California and Pennsylvania and moved jobs to a new 1,500-worker plant in Monterrey, Mexico. It’s not just Hershey’s. Other U.S. candymakers, such as Brach’s and Nestle, have moved production to Mexico. Why? Cheap labor: At a Nestle plant in Toluca, a skilled machinery operator earns less than $20 per day (and we’re talking 12-hour days here, with no overtime pay), while the same job in America would pay more than $20 per hour. Since 1997, the United States has lost more than 10,000 candy-making jobs because of cheap labor and lower raw-materials prices.

Overall, NAFTA led to the loss of hundreds of thousands of U.S. jobs (economists disagree on the numbers, and some say the number was closer to one million jobs lost). Most were in the manufacturing industry in California, New York, Michigan, and Texas. Companies in the automotive, textile, computer, and electrical appliance industries (and candy-making) moved factories to Mexico seeking cheap labor. Even U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, who has praised certain aspects of NAFTA, noted in July that “NAFTA also created new problems for many American workers. Since the deal came into force in 1994, trade deficits have exploded, thousands of factories have closed, and millions of Americans have found themselves stranded, no longer able to utilize the skills for which they had been trained.”

But NAFTA can’t be all bad, right? After all, getting rid of tariffs allows the United States to import Mexican oil cheaper than before, reducing our reliance on Middle Eastern oil. We export a lot of agricultural products to Mexico, increasing business here. In fact, some studies say increased U.S. exports led to the creation of many new U.S. jobs. While some of these are good-paying high-tech jobs such as automotive design, many are lower-wage service-oriented jobs such as baristas, since quite a few good-paying manufacturing jobs moved to Mexico. At the end of the day, NAFTA most likely has hurt blue-collar workers more than white-collar workers. Also, consider the fact that right before NAFTA (1993), we had a $1.6 billion trade surplus with Mexico. Now, we have a trade deficit with Mexico of more than $60 billion. In other words, we used to sell more stuff to Mexico than we bought from them; now we buy way more stuff from them than we sell.

So is NAFTA good or bad for the United States from an economic standpoint? Yes, no, or maybe so, depending on whom you ask. Did jobs move to Mexico? For some industries, yes. But we are exporting to Mexico, increasing employment here, and, some would argue, U.S. industries became more competitive with China and other low-wage Asian countries, something they could not have done if the entire manufacturing chain stayed in high-wage America. And not all the business went to Mexico. The U.S. garment industry, for example, saw an 85-percent decline since NAFTA, but most of those jobs went to Asian countries, especially China and Vietnam.

In truth, losing jobs to Mexico should not be the main concern Americans have about NAFTA. What they should worry about is the fact that we aren’t in charge of our own economy anymore. That’s right: When a country enters into a “free trade” agreement with another country, the new supranational trade regime is the boss, not the industries in the country or even the country’s government.

You see, NAFTA isn’t just about trade and jobs. It’s about a very important but little-mentioned thing called sovereignty. NAFTA is breaking down the barriers that make America an independent country: labor laws, industry standards, tariffs, borders, immigration, etc.

Just look at what happened to Europe. What started as a small “free trade” agreement between a few countries eventually became the European Union, a monster that tells all the European countries what they can and can’t do with their food standards, businesses, economies, immigration policies, borders, and so on — the “will of the people” be damned.

And that’s just it: “Free trade” agreements aren’t written by and for the people, they’re written by and for large corporations and the politicians who seek greater political union via greater economic union.

Photo of workers at a GM plant in Silao, Mexico: AP Images