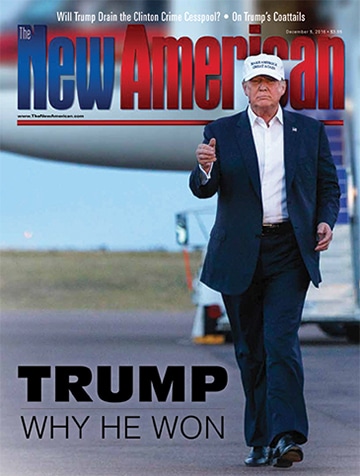

Trump: Why He Won

“They hear the shouts of the peasants from over the hill. All the knights and barons will be riding into the castle pulling up the drawbridge in a minute. All the peasants are coming with pitchforks!” said Pat Buchanan in Nashua, New Hampshire, while waging his insurgent 1992 campaign for the White House. Today, almost a quarter century after pugnacious Pat’s first presidential run, the castle walls have finally been breached by a peasant army that has made Donald Trump the 45th president of these United States.

Love him or hate him, fancy him snake-oil salesman or sincere, there is no question Trump has ridden the anti-establishment wave that in a generation has gone from ripple to tsunami. It’s also plain that he has said many of the correct things, inveighing illegal migration, raw-deal trade deals such as the TTP, internationalism, the media, and the rest of the establishment and its favored social code, political correctness. Lastly, there’s no doubt the establishment resolutely arrayed its forces against Trump, with even many members of his own party disavowing him.

As The New American’s William F. Jasper wrote in August, “Hedge fund billionaires, Wall Street mega-bankers, Hollywood movie moguls, RINOs (Republicans In Name Only), ultra-Left ‘Progressive’ Democrats, and Big Media journalistas have all ganged up on one man. Together with an AstroTurf army of neocon pundits, radical academics, student activists, and street agitators funded by the Big Foundations and Big Government, they have united to stop that one man: Donald J. Trump.” And as TNA’s Alex Newman pointed out online November 10, the mood at the United Nations is “souring” because that man could not be stopped. He wrote, “Some foreign dictatorships, including the Chinese Communist regime, are also fretting, as are globalist UN subsidiary organizations such as NATO.” Trump “has all the right enemies,” TNA editor Gary Benoit told me recently — and, we may add, many of the right friends.

One of the enemies, French ambassador to the United States Gerard Araud, plaintively tweeted that with Brexit and November’s election, “A world is collapsing before our eyes.”

Upsetting the Status Quo

A scheme is collapsing, is more like it. For Araud meant his world. As Trump friend Nigel Farage, interim leader of the U.K. Independence Party, told Time on November 9, the previous day’s earth-shaking results were “Brexit times three.” He elaborated, “It is a bigger country, it is a bigger position, it is a bigger event.... Brexit was the first brick that was knocked out of the establishment wall. A lot more were knocked out last night.” Other bricks lie in the cross hairs, too. Not only has this anti-establishment movement been percolating for decades, but it’s now a roiling-boil, Europe-wide phenomenon, manifesting itself also in Italy’s Five Star Movement, Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France, Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, Poland’s ruling Law and Justice Party, and Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

And triumphant, the most optimistic observers may echo Orbán, who said November 10 that Trump’s victory marks an end of a two-decade period of Western “liberal non-democracy.” The more pessimistic warn that he’s too much of a deal-maker to be an establishment-breaker. Regardless, however, his election is seismically historic. The New York Times noted November 9 that for “the first time since before World War II, Americans chose a president who promised to reverse the internationalism practiced by predecessors of both parties and to build walls both physical and metaphorical. Mr. Trump’s win foreshadowed an America more focused on its own affairs while leaving the world to take care of itself.”

Yet even this doesn’t fully tell the tale. The election season also saw the rise of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a wizened old socialist who’d long wallowed in relative obscurity (by senators’ standards), and between his legions and Trump’s supporters, a majority of the electorate signaled they wanted fundamental change — just not the type Barack Obama has been dishing out. Moreover, where conventional wisdom was that only those who’d been governors and senators (and perhaps highly successful generals) could become president, Trump became the first to win the White House without ever having been in office or the military. Striking.

It cannot be overemphasized that what Trump represents is more important than what he is. As Democrat pollster Patrick Caddell put it in an election-eve November 7 piece entitled “The real election surprise? The uprising of the American people”:

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, sucked from the same trough even if it was from opposite ends. But the critical point that is missed, by almost everyone, was that neither Sanders nor Trump created this uprising. They were chosen vehicles — they did not create these movements, these movements created them.

In less than a day we will know how far this revolt has come. But, make no mistake, whatever the outcome, this revolt is not ending, it is merely beginning.

Trump tapped into this phenomenon masterfully. Note that any of the other primary-season GOP candidates could have done so. But they either didn’t believe in the movement (paging Governor John Kasich) or, and this is most significant, were afraid of the poltroonish patroons of political correctness; they lost sight of what Ronald Reagan called the difference “between critics and box office.” After all, one of the characteristics of the establishment is that it’s a rarefied realm in which political correctness reigns; consequently, even the good people within it can mistake pseudo-elite swill for popular will. Oh, this doesn’t mean political correctness has no sting, as it can and does destroy careers. But this is only because of establishment power — the very thing against which many Trump voters rebelled.

The average person is not politically correct (PC) in a doctrinaire fashion; in other words, he might, regrettably, have been instilled with the false PC suppositions woven seamlessly into our culture, but he doesn’t subscribe to “cutting edge” PC notions, such as that a man is a woman merely because he claims he is. To provide another example, agree with the idea or not, relatively few Americans are actually “offended” by a proposal to halt Muslim immigration.

People also instinctively recoil at Orwellian lexical tyranny. When Trump said that Mexico was sending rapists and drug couriers across our border, that it’s “freezing and snowing in New York — we need global warming!” and that our “great African American President hasn’t exactly had a positive impact on the thugs … destroying Baltimore,” those weren’t the measured words of a Machiavellian politician.

But that is how, when he lets his hair down, the average person speaks.

Most Americans are sick and tired of an oppressive, lie-based social code telling them how to walk and talk and act and think. And November 8 was not just a rebellion against establishment lies, but also its language.

Yet there’s far more to Trump’s anti-establishment victory. In his September Politico piece, “Trump Is Pat Buchanan With Better Timing,” journalist Jeff Greenfield writes, “To a remarkable extent, just about all of the themes of Trump’s campaign can be found in Buchanan’s insurgent primary run a quarter-century ago: the grievances … the dark portrait of a nation whose culture and sovereignty are threatened from without and within; the sense that the elites of both parties have turned their backs on hard-working[,] loyal, traditional Americans.” Pundit and former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan has called this the rebellion of the “unprotected” against the “protected,” the former of whom actually have to live with the problems the latter create, such as illegal-alien invasions.

But why did Trump succeed where Buchanan failed? Of course, we have to mention Trump’s deep pockets and celebrity status, which gave him media exposure, both offered and bought, that almost no one else could match. Yet as Greenfield pointed out, an

overriding reason is that the times have indeed changed. When Buchanan warned of globalism and intervention, the successful Gulf War and the Christmas Day 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union weakened that argument. If there really was a “new world order,” America was unquestionably in charge. Today, with memories of the disastrous second Iraq War, China rising and Russia asserting itself again, anti-interventionism is a lot stronger argument. Immigration, too, is an issue far more powerful today. “Back then, there were maybe 3-4 million illegal immigrants,” Buchanan says. “Today, there are maybe 12 million.” [Note, there could be far more.]

… [Moreover,] the central American promise — that our children would live better than we live — has been thrown into grave doubt, at least for those who are part of “the white working class.” Some 5 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since the start of the millennium; incomes for the average factory worker have been stagnant for just about all of the 21st century.

“Those issues started maturing,” Buchanan now says. “Now we’ve lost 55,000 factories.... When those consequences came rolling in, all of a sudden you’ve got an angry country. We were out there warning what was coming. Now, on trade and intervention, America sees what’s come.”

And what’s gone.

Greenfield also makes the point that widespread Internet and social media allow us to reach countless millions, continually, at a button’s touch. This enables the more rapid spread of bad movements, such as the disastrous “Arab Spring,” and of good ones, such as what many are hoping will be a Western Spring. And it’s just common sense: If people’s only conduit of information is the establishment media — as once was the case — it’s no surprise when they vote for establishment candidates. As with a computer, it’s garbage in, garbage out.

Fundamental Beliefs

Yet the change in civilization is far more fundamental than even the above indicates. Beating around the edges of this phenomenon but blinded by his own biases, New Republic senior editor Jeet Heer addressed the matter in June, taking a few swipes at The John Birch Society in the process. Said he, “Conspiracy theories were long relegated to the fringes of American history, but … with Trump triumphant, we have to see the Birch Society and its style of conspiracy-mongering in a new light. Far from belonging merely to the lunatic fringe, the Birchers were important precursors to what is now the governing ideology of the Republican Party: Trumpism. Bircherism is now, with Trump, flourishing in an entirely new way. Far from being drummed out of conservatism, it has become the dominant strain.”

Of course, Heer ignores that what defines the JBS more than anything else is constitutionalism. On this count it should be noted that Trump is not a constitutionalist, such as Ron Paul, nor is he a “conservative” in the Reagan or Buchanan mold. He didn’t repeatedly inveigh against big government on the campaign trail or warn of a “culture war”; he doesn’t speak of our moral crisis even though we’re sliding toward Sodom and all our man-caused problems are, at bottom, moral ones. Whatever he believes, he’s a master of marketing who exploited what resonated with today’s electorate.

Yet Heer is getting at a real phenomenon, so it’s worthwhile to explain it better than he understands it. He speaks of a “paranoid style” of American politics, originated by the JBS but now mainstream, as he writes, among other things, about Trump’s warnings regarding Muslim immigration. Yet as the saying goes, “It’s not paranoia when they really are out to get you.” Asserting that internationalist statists all across the West are using im/migration to engage in demographic warfare and invade their own nations with socialist-minded (and sometimes jihadist-minded), largely unassimilable individuals who will eventually become citizens is not paranoia. Saying they do this for the dual purpose of overwhelming the votes of traditionalist-minded Westerners and breaking down national cohesiveness and sovereignty is not paranoia. And stating that a percentage of today’s impossible-to-vet Muslim migrants are or will become jihadists is not paranoia. These are facts.

Yet as with anything else, there are rational conspiracy beliefs and nutty ones. Today America is replete with both, partially because of man’s and the Internet’s natures and for another reason: Distrust in America’s institutions abounds. According to Gallup, the percentage of Americans saying they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in various institutions is as follows: the church or organized religion, 41 percent; the medical system, 39; the presidency and the Supreme Court, 36; government schools, 30; banks, 27; organized labor and the criminal-justice system, 23; TV news, 21; newspapers, 20; big business, 18; and Congress is the caboose at six percent.

This cynicism is matched, not surprisingly, by pessimism. Pat Caddell reported on a study by his Armada group called the “Candidate Smith” project, which found that “American politics has entered an historic paradigm” defined by three overriding beliefs: Unlike earlier generations, a great majority of citizens today say their children will be worse off than they are. Eighty-four percent believe (rightly) that different rules apply to the rich and well-connected, with only 10 percent believing everyone has an equal opportunity (in fairness, there has never been a time or place in which the “in” crowd didn’t have advantages; it’s only a matter of degree). And tellingly, 70 percent of Americans believe our country is in actual decline. Given this, it’s no surprise a candidate with the slogan “Make America Great Again” would find success.

Caddell points out that you’d get very different responses if you asked the pseudo-elite establishment types, who live their lives of silk and satin, about the above matters. This is true, too — with perhaps one notable exception: Donald J. Trump.

An accompanying theme of Trump’s campaign was that America was “losing” at every turn because she’s governed by losers. This bold assertion made Trump a “Traitor to His Class,” as Weekly Standard writer Julius Krein put it in a brilliant September 2015 article by that very name. In this time where the pseudo-elite norm is aggressive internationalism — or, as informed “deplorables” may call it, treason — “Nothing is more terrifying to the elite than Trump’s embrace of a tangible American nationalism,” Krein states in his subtitle. (Emphasis in original.) He then goes on to explain part of Trump’s appeal:

Most candidates seek to define themselves by their policies and platforms. What differentiates Trump is not what he says, or how he says it, but why he says it. The unifying thread running through his seemingly incoherent policies, what defines him as a candidate and forms the essence of his appeal, is that he seeks to speak for America. He speaks, that is, not for America as an abstraction but for real, living Americans and for their interests as distinct from those of people in other places. He does not apologize for having interests as an American, and he does not apologize for demanding that the American government vigorously prosecute those interests.

What Trump offers is permission to conceive of an American interest as a national interest separate from the “international community” and permission to wish to see that interest triumph. What makes him popular on immigration is not how extreme his policies are, but the emphasis he puts on the interests of Americans rather than everyone else. His slogan is “Make America Great Again,” and he is not ashamed of the fact that this means making it better than other places, perhaps even at their expense.

His least practical suggestion — making Mexico pay for the border wall — is precisely the most significant: It shows that a President Trump would be willing to take something from someone else in order to give it to the American people. Whether he could achieve this is of secondary importance; the fact that he is willing to say it is everything.

Internationalist Ideology

And that he was the only candidate willing to say it is why he’s the president-elect today. This is something that, as Caddell put it, the establishment types are “psychologically incapable of understanding.” They sneer at the dominant anti-establishment wave, dismissing it as “nativist,” “bigoted,” and “xenophobic.” A prime example is Heer colleague Ryu Spaeth, who writes at the New Republic, “Britain’s Nigel Farage and France’s Marine Le Pen and America’s Trump have all succeeded by sowing fear and hatred of the other. They lead movements that, at their core, are propelled by white revanchism, a raging against an increasingly globalized world that has threatened white power and diluted white identity.” As these pseudo-elitists hurl their names and miss the mark, however, they’re clearly ignorant of the fact that it is not their targets who are radical — and radically wrong. It is they.

Imagine that a primitive Amazonian tribe were being overrun by outsiders; or consider Tibet, which has been inundated with millions of ethnic Chinese during China’s domination of the country. If a tribesman or Tibetan lamented this state of affairs, would our leftists call him “racist” and xenophobic? On the contrary, such happenings may inspire anthropologists to cry, “This is demographic and cultural genocide!” Yet the reaction is quite different when the same is visited on Western peoples. Then they call it “multiculturalism” and say, “Our strength lies in our diversity.”

Moreover, if a people were asked, “Do you want to be replaced with foreigners, who won’t assimilate or won’t be asked to do so, and have your culture extinguished?” what people would say yes? But the establishment didn’t ask. There was no referendum.

They just did it.

Also note that no small number of non-Western nations, such as Japan and Saudi Arabia, have no or virtually no immigration. Yet establishment types never demand they be strengthened with diversity; this they reserve only for Western lands. We perhaps should wonder why.

As for wonderment, many establishment types are, again, incredulous that the “great unwashed” aren’t sticking to the internationalist program. But could the following provide a clue as to why? An e-mail released by WikiLeaks in October revealed that Hillary Clinton said in a private, paid 2013 speech to a Brazilian bank, “My dream is a hemispheric common market, with open trade and open borders.” This is par for the establishment course. Andrew Neather, former aide to ex-British Prime Minister Tony Blair, confessed in 2009 that the massive immigration into the United Kingdom over the previous 15 years was designed to “rub the Right’s nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date.” And Swedish Social Democrat politician Mona Sahlin unabashedly proclaimed in 2001, “The Swedes must be integrated into the new Sweden; the old Sweden is never coming back.” With leaders like that, who needs traitors?

Of course, truly “open borders” means the United States would cease to exist. Mind you, it’s easy for pseudo-elites to accept such an outcome. They can engage in moral preening as they pontificate about the brotherhood of man and fancy themselves above the notions of nations and borders (behind the walls of their well protected, palatial abodes). And their wealth may allow them residences in many countries; they may spend much time overseas. For they are philanderers of nations. Yet the average person is married to the land; he has nowhere to run. If the establishment mucks things up, he goes down with the ship.

What many internationalists don’t understand, because their self-professed enlightenment is a delusion, is that they’re bucking man’s nature. Properly understood, a nation is merely an extension of the tribe, which itself is an extension of the family; thus, nationalism is natural, a population-level version of family patriotism. And when a country becomes Balkanized enough, either it dissolves — or an iron fist of tyranny appears, as “savior,” and keeps the bickering groups in line.

Trump’s Trajectory

As for Trump, his nationalism has carried the day, for now, yet he isn’t most properly analogized to Pat Buchanan. Rather, his election is historic for yet another reason: As I pointed out in January, Trump was our first “European-conservative” American presidential candidate. Unlike Buchanan and much like Marine Le Pen or Nigel Farage, Trump is indifferent to quite liberal on social issues, and he accepts the statist status quo. He simply rejects internationalism. And in this he is, like it or not, a man for our time. In “Liberalism and Conservatism: The Engine and Caboose of the Train to Perdition” (The New American, November 7, 2016), I pointed out that a given time’s conservatives merely reflect the previous times’ liberals, as the political spectrum continually moves “left.” And as we follow in Europe’s footsteps — with secularization, declining morality, and burgeoning government — and as our people begin to resemble the Old World’s worldview-wise, so do our leaders.

There is a lesson here. Just as a nation may get the government it deserves, reformers can only reform rightly insofar as they morally are well-formed. The hit the establishment took November 8 was uplifting, and we should wish President-elect Trump great success in advancing his aims, insofar as they’re constitutional. We should also hope he truly will trump the establishment. Yet we must remember that he is only one man; it’s the movement that matters. Whatever Trump attempts, we can and should augment (or correct) it by neutralizing establishment schemes with nullification, which Thomas Jefferson called the “rightful remedy” for all federal usurpation. Moreover, we should dismiss judicial supremacy as the extra-constitutional power it is, for to accept it, as Jefferson warned, would make our Constitution a “suicide pact.” In addition, we can elect members of Congress who understand their constitutional powers — for example, those allowing them to rein in the judiciary — and aren’t reluctant to exercise them; as it stands now, congressmen opt to let unelected (and unaccountable) judges “settle” contentious issues rather than do so themselves, alienate part of the electorate, and give opponents ammunition for campaign-time political ads. This, of course, leads to distorted government. For how can there be the founder-envisioned balance of power among the three branches if one branch neglects to exercise its powers? If Congress refuses its turn at the wheel, it should be no surprise when the presidency and courts steer us toward an abyss.

Yet national suicide will still be our lot without one crucial ingredient. We can talk about constitutionalism till we’re blue in the face, but our second president, John Adams, told us in no uncertain terms, “Avarice, ambition, revenge and licentiousness would break the strongest cords of our Constitution, as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Does “moral and religious” describe us today? Adherence to a set of rules (the Constitution, for instance) requires a sense of honor in the people. Furthermore, it requires a belief that rules can have a basis in more than just man’s preference. As to this, I’ve often mentioned Barna Group research indicating that a staggering 83 percent of teenagers in 2002 (adults today) said that “morals” were relative; in other words, they don’t believe in the most important, most fundamental rules of all — God’s laws — which are what morals reflect. Of course, if even what we call right and wrong were relative (which essentially means they don’t exist), why would we consider constitutional dictates and prohibitions anything but relative? Another way of saying this is: Why then would we consider the Constitution anything but a “living document”?

Moreover, if right and wrong were just a matter of “perspective,” what could be objectively wrong with violating any set of rules? And if we accept the relativistic Protagorean notion that “Man is the measure of all things,” which would include laws, then it’s no surprise when we start to become a land of men and not laws. This is why philosophy matters: Get “First Things” wrong, and what flows from them will be no better.

An apocryphal saying tells us, “America is great because she is good, and if America ever ceases to be good, she will cease to be great.” You may or may not consider a battle to have been won on November 8, but the moral and spiritual battle for the soul of America is waged every single day. And making America great again requires making her good again. Take care of that, and the elections — and the establishment’s disestablishment — take care of themselves.

Photo: AP Images