What’s Behind Bernie’s Socialism?

At a town hall meeting in New Hampshire on October 30, senator and presidential candidate Bernie San-ders attempted to clarify in what sense he is a “socialist.” One voter in attendance, echoing the beliefs of many Americans, remarked, “I come from a generation where that’s a pretty radical term — we think of socialism (with) communism. Can you explain to us exactly what that is?” Sanders responded, in part: “If we go to some countries, what they will have is health care for all as a right. I believe in that. They will have paid family and medical leave. I believe in that. They will have a much stronger childcare system than we have, which is affordable for working families. I believe in that.”

Sanders went on to clarify that he regards himself as a democratic socialist: “What I mean by Democratic socialism is looking at countries in Scandinavia that have much lower rates of child poverty, that have a fairer tax system that guarantees basic necessities of life to working people. Essentially what I mean by that is creating a government that works for working families, rather than the kind of government we have today which is largely owned and controlled by wealthy individuals and large corporations.”

Sanders, the only self-acknowledged socialist ever to be elected to the U.S. Senate, is careful to distinguish “democratic socialism,” which supposedly distinguishes a democratic political system alongside a socialist economic system, from more authoritarian and even totalitarian forms of socialism such as Marxism, Stalinism, Maoism, and communism generally.

In making such a distinction, Sanders is hardly alone. A number of influential socialists, such as Rosa Luxemburg, Eugene Debs, Erich Fromm, and Howard Zinn, view “democratic socialism” as “socialism from below,” demanded and implemented by the grassroots, and “authoritarian socialism,” such as Stalinism, as “socialism from above.” The Scandinavian model of democratic socialism mentioned by Sanders is a popular talking point among democratic socialists, inasmuch as countries such as Denmark and Sweden appear prosperous, happy, and free despite being socialist.

While polls suggest that Bernie Sanders is unlikely to capture the Democratic nomination for president, his newfound national prominence as a presidential candidate has spurred a renewed interest in socialism. Given America’s struggles with violent crime, chronic unemployment, healthcare affordability, and the quality and cost of education, what could possibly be wrong with the sort of socialism that the likes of Sanders and Scandinavia believe in?

The Evolution of Socialism

Modern socialism’s roots may be traced back at least as far as the French Revolution, although earlier experiments in forced communitarianism, such as the radical Digger and Leveler movements that sprang up during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century, have also cast long shadows.

Socialism in its many subvarieties is but part of a larger political stream of thought that we might call “utopianism,” which presumes to create a social order contrary to human nature. In addition to socialism, the utopian impulse has given rise to radical anarchism, as well as to experiments with coercive religious communalism, including the Jonestown commune of the Peoples’ Temple, led by Jim Jones (an atheist who deceived his followers with fabricated “healings” and supposed religious miracles).

But of all the manifestations of utopianism, socialism in its many guises has proven the most enduring and — at least in our day — by far the most popular. It is often divided into revolutionary socialism — of the sort that convulsed the world in 1848, the Russian Empire in 1917, China in the 1940s, Cambodia in the 1970s, and so on — and democratic socialism, which has found favor in the parliaments and Congresses of every Western country since at least the mid-20th century. Revolutionary socialism has appeared in several flavors, but may be roughly divided into national socialism (of which German Nazism is the best-known example), which appeals to nationalism and racial exceptionalism to justify the implementation of state control over the private sector, and international socialism, which seeks to export socialism worldwide and has as its goal a unitary global socialist order. Democratic socialism, meanwhile, has been known by many names (including, in the United States, “progressivism”), but may be characterized in general as an effort to institute an egalitarian socialist order by “working within the system,” using a gradualist (or “Fabian”), long-term strategy to persuade democratically elected governments to legalize socialist programs such as government-controlled healthcare and school systems.

The fruits of Fabianism: Federal employees in Washington demonstrate on behalf of a higher minimum wage. These government workers probably have no idea that the pedigree of the government-mandated “minimum wage” can be traced back to socialist utopians of 200 years ago. (Photo credit: AP Images)

The difference between revolutionary socialism, especially Marxism and its ideological offspring, and democratic socialism is primarily a matter of degree; communism has been characterized as “socialism in a hurry” because of its insistence on the violent overthrow of “bourgeois” society and government. In point of fact, the League of the Just, the underground group of European revolutionaries who became the first proponents of communism, considered themselves socialists. Friedrich Engels, the wealthy colleague and patron of Karl Marx who helped bankroll the early Communist Party in Europe, explained in the preface to the 1888 English edition of the Communist Manifesto the virtual equivalency of communism and socialism as they were then understood:

The history of the Manifesto reflects the history of the modern working-class movement; at present, it is doubtless the most wide spread, the most international production of all socialist literature, the common platform acknowledged by millions of working men from Siberia to California.

Yet, when it was written, we could not have called it a socialist manifesto. By Socialists, in 1847, were understood, on the one hand the adherents of the various Utopian systems: Owenites in England, Fourierists in France, both of them already reduced to the position of mere sects, and gradually dying out; on the other hand, the most multifarious social quacks who, by all manner of tinkering, professed to redress, without any danger to capital and profit, all sorts of social grievances, in both cases men outside the working-class movement, and looking rather to the “educated” classes for support. Whatever portion of the working class had become convinced of the insufficiency of mere political revolutions, and had proclaimed the necessity of total social change, called itself Communist.... Thus, in 1847, socialism was a middle-class movement, communism a working-class movement. Socialism was, on the Continent at least, “respectable”; communism was the very opposite. And as our notion, from the very beginning, was that “the emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself,” there could be no doubt as to which of the two names we must take.

Engels’ distinction between “working class” communists and “middle class” socialists is misleading. The theoreticians, leaders, and financiers of both movements were typically middle-class intellectuals (such as Marx) and upper-class money men (such as Engels). In particular, Robert Owen, the Welsh social reformer whose Owenite movement in England and America is credited with coining the term “socialism,” was a middle-class merchant and mill manager, as well as a successful entrepreneur who eventually became a prominent member of the elite Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. Owen set up utopian communes in Britain and America, where he advocated causes such as the eight-hour workday. His experimental communities were regarded with narrow suspicion by most early Americans because of their repudiation of free enterprise and the private ownership of property.

Owens’ first American community, New Harmony in Indiana, lasted only two years before collapsing. One disaffected member of New Harmony recognized that the community failed because of its repudiation of personal property rights and liberty, admitting: “We had a world in miniature — we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result.... It appeared that it was nature’s own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us … our “united interests” were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation.”

Late in life Owen, who had renounced Christianity as a young man, became intensely interested in spiritualism, in which he immersed himself for the last four years of his life.

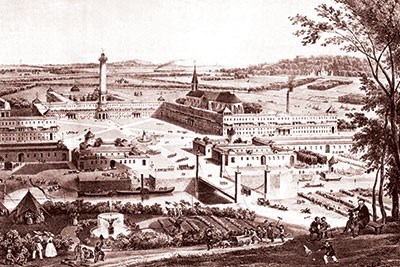

The followers of Charles Fourier, another early utopian socialist, set up cooperative communities (which he called “phalanxes”) in Europe and America; “Fourierism” found expression in locations as far-flung as Ohio, Texas, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, and counted among its adherents prominent American author Nathaniel Hawthorne. Fourierism sought to eradicate poverty by raising wages and establishing a minimum standard of income for all members of the community. Fourier was also intensely interested in human sexuality, and encouraged complete sexual freedom in his phalanxes. He also was an early proponent of homosexuality and homosexual rights. His program called for nothing less than total sexual emancipation and for universal education. Fourier, who died in 1837, was also one of the earliest political reformers to call for a “new world order” of universal harmony and international cooperation.

These men and others were the first of the utopian, non-revolutionary socialists, to whom modern democratic socialism owes much of its ideological pedigree. The interest in such conceits as state-mandated minimum wages and eight-hour workdays is as characteristic of socialism today as it was two centuries ago — but today, such policies have been almost universally embraced and are seldom even acknowledged as socialist innovations. Meanwhile the repudiation of Christianity and of Judaeo-Christian morality evident in both Fourierism and Owenism is still very much a feature of the modern Left — the ideological heirs of Owen, Fourier, and their ilk.

The other early strain of socialism, the communism of Marx and Engels, had its organizational roots in the European revolutionary underground that grew out of the French Revolution and its aftermath. Philippe Buonarroti, for example, was one of Marx’s most important influences. A member of the Babeuf conspiracy in late revolutionary France, Buonarroti was a professional agitator and subversive who advocated a conspiratorial and revolutionary path to radical socialism. His History of Babeuf’s “Conspiracy of Equals,” based on his own experiences, was a recipe for revolutionary egalitarianism that was a must-read for 19th-century socialist revolutionaries, including Karl Marx.

Even a cursory reading of Marx’s most famous work, the Communist Manifesto, reveals Marx’s lust for revolutionary violence, a passion clearly not shared with more genteel utopians such as Owen and Fourier. Yet in reality, how different was Marx’s communist program? Marx — like Owen and Fourier — was opposed to Christianity and traditional morality, and their eradication by force became one of the paramount goals of the communist program. Marx, like other socialists, believed that capitalism and inequality of wealth were responsible for all of the ills afflicting humanity, and sought to eliminate them by eliminating private property. However, Marx and the communists differed very clearly from other socialists of the day in ambition; where Owen, Fourier, and others were content to publish pamphlets and set up small utopian communities wherever they could attract a sufficient following, the communists sought nothing less than the complete overthrow of the existing sociopolitical order, by violent means and everywhere in the world.

In pursuing these goals, the communists proved to be far more resourceful and better organized than other socialists; in the same year (1848) that the Communist Manifesto was first published, nearly every nation in Europe was convulsed by revolution in what turned out to be the opening spasm of communist revolutionary activity that captured the world’s two largest countries (Russia and China) in the 20th century, not to mention countless smaller states all across the globe.

The Communist/Socialist Program

The Communist Manifesto articulates a clear, simple program for the advancement of communism, a program that must be held to be the first comprehensive enunciation of the socialist program as well, except on a different timetable. Most of the elements of Marx’s famous “ten planks of Communism,” which appeared very radical when they were written, are almost universally accepted today. They are:

1. Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

3. Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

4. Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

5. Centralization of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

6. Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

7. Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

8. Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

9. Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.

10. Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children’s factory labor in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, &c, &c.

Utopia: Socialist communes built by the followers of Charles Fourier, such as this 19th-century artist’s conception, failed because they experimented in a social order contrary to human nature, in which private property was abolished and traditional family values were replaced with complete sexual freedom.

Of these, numbers two (heavy progressive income tax), five (a monopolistic central bank), six (state control of communication/media and transportation), and 10 (“free” public schools and abolition of child labor) have been nearly or entirely accomplished in the United States and most other Western countries. Most of the others are well on their way to fruition in the United States. Number one, for example (the abolition of private property) has not yet been fully realized, but private property rights have been diluted to the point of being nearly meaningless, thanks to the proliferation of heavy property taxes, environmental and zoning regulations, and countless other government controls limiting the ways in which “private” land may be used.

Number four (the confiscation of the property of emigrants and rebels) has only recently gained momentum, with asset forfeiture laws allowing the state to strip property from people accused of criminal activities, leading to flagrant, systemic theft of private assets by local, state, and federal governments alike. Meanwhile, as more and more Americans living overseas are forced to pay ever-heavier taxes to Washington (no other country besides Eritrea seeks to tax its citizens living and working abroad), increasing numbers of them are seeking to renounce their American citizenship. The federal government has responded by branding them disloyal and levying enormous new excises that, for wealthy individuals, may amount to confiscation of a significant portion of their assets.

Thus the “Communist” program of Karl Marx is being brought to fruition in the United States and the rest of the Western world, but largely without revolution, bloodshed, and purges — at least not yet. While the communist movement in Europe sparked a number of violent uprisings during the 19th century. It made little progress on the other side of the Atlantic — at least not openly.

But in America, the decades after the Civil War saw the birth of a new political movement every bit as foreign to American traditions and hostile to personal liberty as revolutionary communism, but with a gentler countenance: “progressivism.” Birthed as a movement for broad social reform in Europe and the United States, by the end of the 19th century, the “progressive” agenda had won many adherents in Washington, including Theodore Roosevelt and Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge. Senator Beveridge’s legislative activities in the first years of the 20th century embodied the progressive program; among other things, Beveridge sponsored a bill for federal meat inspection, fought for the passage of anti-child labor legislation, and supported the federal control of railroads, the institution of an eight-hour work day, and the regulation of “trusts” (Big Business). Senator Beveridge, like most progressives, was also a strong supporter of American interventionism, of which the Spanish-American War was viewed as a noble example of enlightened empire-building. Self-styled progressives such as Woodrow Wilson popularized the notion that America’s proper role was to make the world safe for democracy. Progressivism also figured prominently in the push to create a universal public education system championed by progressive John Dewey, in the fledgling conservationist/environmental movement fostered by Theodore Roosevelt, and in the drive for the federal government to have direct regulatory authority over the business sector. All of this, and much more, was defended in the name of using the power of the state to achieve positive good, to engineer improvements in society that the private sector, left to its own devices, would supposedly neglect.

Yet for all their benign rhetoric, the progressives were bitter foes of the ideals of America’s Founding Fathers and of the limited constitutional government they created. Wrote historian William Leuchtenberg: “The Progressives believed in the Hamiltonian concept of positive government, of a national government directing the destinies of the nation at home and abroad. They had little but contempt for the strict construction of the Constitution by conservative judges, who would restrict the power of the national government to act against social evils and to extend the blessings of democracy to less favored lands. The real enemy was particularism, state rights, limited government, which would mean the reign of plutocracy at home and a narrow, isolationist concept of destiny abroad.”

Over the last century, progressivism has carried the day in the United States, with activist government coming to dominate virtually every aspect of what was once the private sector. It is taught and learned unquestioningly in public schools, universities, and law schools, usually under the banner of “liberalism” or “progressivism” — but it is socialism all the same, listing as its achievements many of the ideals of the Owenites, Fourierists, and communists.

In the meantime, more overt socialism continued to evolve, with the organizational starting point of modern democratic socialism probably being the founding, in London, of the Fabian Society in 1884. Unlike the communist revolutionaries, the Fabians were dedicated to the promotion of socialism by gradualist means that mimicked the patient, piecemeal military strategy of Roman general Fabius Maximus. Fabius wore down the invader Hannibal and his formidable army by waging a years-long war of harassment and attrition that eventually led to the Carthaginian conqueror’s withdrawal from Italy. Aptly, the Fabians adopted as their first coat of arms a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and their symbol the patient tortoise.

From its inception, Fabianism attracted many prominent supporters, including George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, and Annie Besant. They advocated a minimum wage and a national, government-run healthcare system, among many other familiar projects. They proved ambitious organizers. In 1895, they founded the London School of Economics, which remains one of the world’s most influential centers of economic thought and policymaking, and in 1900, the Labor Party, which became the dominant political party in Britain during much of the 20th century, ushering in legislatively much of the socialist program in Britain. In other parts of the Anglophone world, “liberal” political parties like the Democrats in the United States and the Liberal Party of Canada rushed to align their priorities with those of Britain’s Fabian-inspired and -controlled Labor Party.

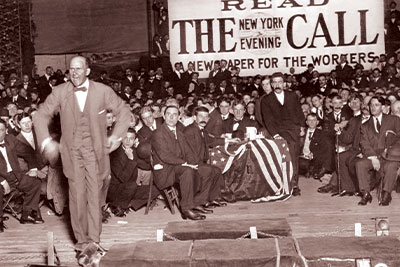

Meanwhile, socialism in America was organized into an overt political force with the establishment of the Socialist Party of America in 1901, a merger of the Social Democratic Party of America and the Socialist Labor Party. Drawing much of its early support from labor unions, the Socialist Party soon had its own champion, the indefatigable Eugene Debs, who dedicated his life to the transformation of American society along socialist lines. Whereas the progressive movement was a way to enact the socialist agenda without calling it by name, the Socialist Party and its flamboyant leader provided pressure from the radical Left, propagandizing the masses without successfully electing anyone to actual positions of government power.

Debs, a five-time Socialist Party candidate for president, got his start on the radical fringes of the Democratic Party in the late 1800s, organizing labor strikes. He was eventually jailed for his agitation, and embraced the socialist program while in jail. Because of his exceptional oratorical skills and personal charisma, Debs rose rapidly to prominence in the American socialist movement.

As we have seen, the establishment Left, then as now, self-identified as “progressive” rather than “socialist,” but only because “socialism” was such an unpopular term. In point of fact, the American progressives, in both style and substance, were almost indistinguishable from the more honestly named Fabian Socialists of England, while the firebrand Debs and his followers resembled more the Old World revolutionary agitators than boardroom socialists.

Agitation: Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist Party in the United States in the early 20th century, speaks to members of a worker’s union. The charismatic Debs, like Bernie Sanders today, was the face of American socialism. (Photo credit: AP Images)

It is worth noting that the Socialist Party of America was a coming together of both labor union-centered socialism (sometimes called syndicalism) and democratic socialism. And the latter group, beloved of presidential candidate and Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, is indistinguishable in its turn from American progressivism and British Fabian socialism. All of these groups attempt to institute socialism by popular consent and are content to work within the forms of the law to accomplish their ends instead of trying to violently uproot existing laws and social norms by revolutionary subversion.

Among those aims that have successfully been achieved legislatively in the United States are the federally mandated minimum wage and 40-hour work week; the prohibition on child labor; federal control over the agricultural, banking, manufacturing, and healthcare sectors; federal limitations on business activities and private property ownership in the name of environmental protection; government subsidy of college student loans and academic research; federal control over public schools and education; a heavy graduated federal income tax; and the federal monopoly on the money supply and control of the banking sector, as embodied by the Federal Reserve. These and a myriad other federal intrusions into the workings of the formerly free market and curtailment of the formerly sacrosanct right to private property are all elements of the socialist program, a program that seeks to substitute for private, consensual enterprise and individual, God-given rights forced, centrally-controlled economic activity and egalitarian “collective” rights enforced by state decree.

Bernie Sanders’ own presidential platform includes such socialist staples as a sharp increase in the minimum wage, creating a “single payer” government healthcare system, creating a universal government child care program, breaking up financial corporations deemed too large, instituting a government program to provide job training for young people, legislation to strengthen the power of unions, and legislation to impose a carbon emissions tax on businesses. This on top of the vast web of existing socialist controls — which Sanders enthusiastically supports — over private property, enterprise, and nearly every God-given right once protected by the Bill of Rights. Sanders is, for example, a perfervid supporter of gun control and heavy, progressive, ubiquitous taxation, and, in general, government involvement in every conceivable aspect of our private lives.

But inasmuch as the aims of progressivism, Fabian socialism, and communism — as well as the democratic socialism so beloved of Bernie Sanders — are all the same in the long run, so must they have similar outcomes for humanity, sooner or later.

And what are those outcomes? In his magisterial work on socialism, economist Ludwig von Mises pointed out that the basis of economic activity is voluntary exchange, which is enabled by economic calculation. Absent voluntary exchange, rational economic calculation (pricing and valuation) is impossible, except for very simple economic domains such as individual households. Wrote Mises: “Without calculation, economic activity is impossible. Since under Socialism economic calculation is impossible, under Socialism there can be no economic activity in our sense of the word. In small and insignificant things rational action might still persist. But, for the most part, it would no longer be possible to speak of rational production. In the absence of criteria of rationality, production could not be consciously economical.”

Thus socialism as an economic system is fundamentally irrational and impracticable. Its universal implementation would trigger a swift end to the complex, extended economic order that the free markets have built up over the centuries. It is possible only piecemeal, as arid expanses of centralized control within the fertile, life-giving pastures of the free markets. For a time, the successes of capitalism confer on socialism — which parasitizes free enterprise like a lamprey its host — the false appearance of vitality. But even fragmentary socialism of the type that now characterizes the American economy is always retrogressive, not progressive, destructive and not productive. It — and not “irrationally exuberant” capitalism — is responsible for mass impoverishment, recessions, and depressions, yet it is seldom indicted nowadays in the courts of media or public opinion.

Socialism — in the guise of national healthcare; a graduated income tax; an inflationary central bank (the Federal Reserve); government subsidies of agriculture, automobiles, and a myriad other sectors; or any of a host of other illegitimate government controls on the economy — is inflicting a death of a thousand bureaucratic cuts on the American and world economy. And because it is almost never held to account, more socialism is always demanded as a remedy. ObamaCare, for example, did not appear out of thin air, but was proposed as the solution to the havoc already wrought on the healthcare sector by previous socialist half measures (Medicare and Medicaid chief among them).

Because socialism is fundamentally utopian and irrational, it also places great emphasis on uprooting and destroying the entire social fabric upon which the free market and a legal system limiting the power of government rests: the traditional moral values practiced by Western society for centuries. This is the reason that most socialists are instinctively hostile to religion, for example, and supportive of all policies that militate against the family and practices destructive to it, like sexual license, abortion, homosexuality, and the sexualization of children.

In the end, socialism can only survive by growing, throttling the life out of the free markets, destroying the economic growth that has been the wellspring of human progress for half a millennium, and implementing ever-more radical attacks on the traditional moral and social order. The havoc wrought by socialist policies inevitably produces pressure for more socialist measures to solve them, as with America’s never-ending but wholly manufactured “healthcare crisis.” The loss of economic freedom will eventually lead to the loss of all other freedoms, just as Marx envisioned. So-called class distinctions will be obliterated as humankind descends into the abyssal equality of universal serfdom. Socialism, then, regardless of its flavor, is the willful campaign to extinguish the lamps of civilization and eradicate every vestige of human progress.

Bernie Sanders and his fellow socialists from Washington to Scandinavia may refuse to accept socialism’s true nature. But Senator Sanders likely also does not recognize that his chief rival, Hillary Clinton, is also a socialist, as are many of the Republican presidential candidates (in fact, Sanders’ cumulative Freedom Index score, as good a yardstick as any of socialist leanings, is 26 percent which, while no great shakes, is significantly higher than “Democrat” Hillary Clinton’s 19 percent). Indeed, whether “progressive,” “liberal,” or even “moderate,” nearly everyone in Washington in both parties supports most of the planks of the socialist movements in days past, from minimum wages to the Federal Reserve to graduated income taxes. The only difference between them and Bernie Sanders is that the senator from Vermont is a little more honest. But they are all equally culpable in waging a campaign that, sooner or later, must destroy civilization, if allowed to run its ruinous course.