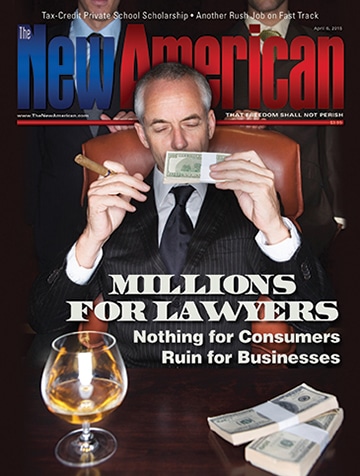

Class Action Lawsuits: Millions for Lawyers, Nothing for Consumers, Ruin for Businesses

Manufacturers of consumer goods in the United States have a lot to fear from the government, and becoming the target of a class action lawsuit is right up there in the first tier of those concerns. An astounding 52 percent of major corporations are engaged in class action litigation right now. Federal judges have complete discretion about whether to certify a class action lawsuit, and then whether to approve large attorney fee requests. Once certified as a federal class action, an otherwise small lawsuit turns into a massive cash drain for the target company and a money machine for the lawyers.

The real goal of many of these lawsuits is to extract a large attorney fee for the law firm bringing the case. The class of alleged consumer victims — their clients — is often a secondary concern, and is usually left with relatively little financial benefit, sometimes merely a few cents.

Class action lawsuits were originally set up to make it easier for a large group of people, all of whom were allegedly harmed by a defendant, to sue as a group. Class actions are defined on Lawyer.com as follows:

A class action lawsuit is when one (or sometimes a few people) file a single lawsuit on behalf of a larger group of people (called the “class”) who have the same or similar legal claim. Who speaks for the class? The lead plaintiff, sometimes called the “named plaintiff,” or “class representative.”

In most consumer product class action cases, the damage to each member of the class — a person who used the product at some point — is minor. The class action format makes it economically feasible to get redress against a company that has allegedly damaged or defrauded a large number of people in the marketplace for a small amount each.

There have been some larger, high-profile cases that have resulted in larger damages for each class member, such as for defective medical devices, tainted building materials, malfunctioning automobiles, and death due to addiction to cigarettes, but they are the numerical minority. You can imagine how disconcerting it must be to find out that your heart pacemaker was not manufactured correctly, or that your car could suddenly accelerate without any notice. In those situations, the class action is a helpful means to address the problem of a large number of claimants.

But most class actions are much more mundane, and are brought on behalf of purchasers of regular consumer products that one would find on a store shelf. That type of case isn’t about much money or life disruption for consumers. For example, some recent cases were on behalf of buyers of Red Bull energy drink, Ghirardelli Chocolates, and VitaminWater, and small performance defects in PC computer chips in 15-year-old computers. When a consumer “victim” purchases a product that is slightly less impressive than expected, she does not run breathlessly to her attorney for redress; rather, lawyers drive the business. They find a “class representative,” a person to use as a placeholder for a consumer product lawsuit.

How They Work

In the rarefied world of the large class action law firm, cases are selected exactly backward from what the well-meaning person would expect. Law firms now do research to identify a suitable target company, write a lawsuit against that defendant (without that company knowing anything about it), and then — and only then — find a “lead” plaintiff to represent the class of “victims.”

Once the case is in place and filed in court, the lawyers pressure the target defendant company to negotiate some sort of token compensation for the users of the product, plus a large attorney’s fee, which is in essence a payoff to drop the matter.

The law firm then departs after obtaining its thousands or millions of dollars from the defendant company, and the consumers who bought the product may get a few dollars apiece, or a coupon for some more of the offending items, along with a cumbersome process to obtain their meager winnings.

A typical example of a class action lawyer bonanza is the lawsuit against one franchise of Backyard Burgers, a chain of about 65 burger restaurants based in Nashville, Tennessee. One of its franchisees in Nebraska negligently printed credit card expiration dates on its receipts for several months. When the lawyers swooped in to save the day and sued on behalf of the class of “victims,” namely all customers who bought a burger on a credit card in late 2010 through April 2011, they netted each victim a coupon for a free soft drink with the purchase of a burger if the victim submitted a claim form and an affidavit under oath, but only if the customer could find the receipt from four years ago. The lawyers will be drinking something more expensive, however, since they got $1.2 million for righting this grievous wrong.

Even smaller class action cases can reap a rich harvest. A 2012 case in Boston, Massachusetts, Domenico v. National Grange Insurance, involved less than $14,000 in damages, derived from the insurance company failing to pay a small sliver of interest to a bunch of claimants in a much larger insurance lawsuit. The lawyers wanted $136,000 (at $550 per hour) for ferreting it out and getting those few cents for each person in the class. Large numbers of such cases grind through the state and federal court systems on a daily basis.

Here are two other astounding facts about class action cases from Chicago law firm Mayer-Brown (one of the largest in the world), in a study that they did of cases open in 2009: First, of the 148 class action cases reviewed, not a single one went to trial. They were all settled or dismissed. Class action lawyers never want to go to a trial, but instead try to force a settlement. To force the target company to the negotiating table, they create a huge burden for the target company by the way of complying with paperwork requests, such as disclosing all of their financial records, internal communications, scientific research, e-mails, and marketing information. It just becomes cheaper to pay them off to go away.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg lamented that “a court’s decision to certify a class … places pressure on the defendant to settle even unmeritorious claims.” Some of these lawsuits are high-risk “bet the company” cases, where a negative outcome could cause bankruptcy, dissolution, or ruin. Hence, settlement is the only reasonable business decision.

The second conclusion from the Mayer-Brown study is that less than one percent of the eligible class in these lawsuits usually makes a claim for benefits. Sometimes less than a tenth of a percent does. This statistic makes the real issue quite plain, namely that it is the lawyers who benefit most from these cases. The little Domenico case from Boston cited above drew a stinging rebuke from the judge, “Plaintiff’s counsel … clearly benefited most from this action.”

Why is this type of lawsuit legal at all? Because the lawyers themselves write their own ethics rules. The American Bar Association, which is comprised of lawyers who profit handsomely from these cases, unsurprisingly does not find any ethical problem with them.

Who Benefits?

Consumer product lawsuits are a “shooting fish in a barrel” issue for large law firms, but not for the consumers. For example, Red Bull energy drink became a target of lawyers in a New York class action lawsuit filed in 2013. According to the official complaint document, which lays out the case against the makers of the drink, the “class representative” bought a can of Red Bull, expecting that it would fulfill its advertising slogan, “Red Bull gives you wings,” and that it “revitalizes body and mind.”

It is only exaggerating slightly to say that when feathered appendages did not appear on the customer, and he did not feel “revitalized” after imbibing, the big law firm easily convinced the gentleman to sue the offending beverage company. The poor sap alleges that he was “lured” by the “puffery” of the company’s advertising into buying the drink, but that it had less caffeine than a Starbucks coffee, and thus he was the victim of an unfair and deceptive trade practice. Plus, he couldn’t fly.

Hopefully, his wings will be renewed by the prospect of using his winnings in the case: He (and other disappointed customers) gets a $10 coupon for more of the allegedly impotent Red Bull energy drink. The lawyers, however, can afford some real wings, since they pocketed $4.75 million for their work, enough to buy a private jet.

In a similar case, involving Ghirardelli Chocolate Bars, the manufacturer allegedly misrepresented the proportion of white chocolate in a particular product. Victims can console themselves with their coupon for 75 cents toward the purchase of another bag of Ghirardelli comfort food, while the lawyers’ consolation comes in the form of a $1.665 million payout.

A large number of class actions result in no benefit whatsoever to consumers, but solely to the lawyers. For example, lawyers brought a class action against CocaCola, the parent company of VitaminWater, alleging that promotion of its health benefits was misleading. They pointed to advertising claims such as “Vitamins + water = all you need,” and “it will keep you healthy as a horse” as untrue, because the bottled beverage had too much sugar and not enough nutrients.

Consumers didn’t get a penny out of that case. Its only outcome was that the company has to change the labels and advertising for the product, presumably so consumers will no longer make equine health comparisons or suffer the delusion that it will make them feel healthy. The lawyers, however, will feel good indeed, with the court-approved $1.2 million attorneys fee that they are about to receive.

And then there is the jaw-dropping settlement negotiated with Visa and Mastercard. In this case, merchants who accepted those credit cards for purchases were allegedly pressured into doing so, and paid a slightly larger transaction fee than they should have paid. As compensation, these merchants will get a rebate for one-tenth of one percent (.001) of their charged sales over eight months, while the lawyers get $544,800,000. Yes, you read that right: over half a billion dollars. That isn’t even the biggest one on record, but it will make a lot of yacht payments. By contrast, a storeowner who made $100,000 worth of credit card sales during that period would be entitled to a hundred bucks.

A Case Study in Attorney Greed

Lawsuits involving dietary supplements for joint health made of glucosamine HCl and chondroitin show a lot about what has gone wrong with the class action legal system. These supplements have been developed and sold for decades by many manufacturers in order to help ease human and animal joint pain from cartilage deterioration or arthritis.

These products work by stopping the body from making chemicals that cause inflammation and pain, and by blocking production of enzymes that break down cartilage. The ingredients also reinforce the strength and lubrication ability of cartilage cells in joints. It is a complex natural process that allows the body to heal and restore itself, and the action of the supplements takes place in the joints on the cellular, DNA, and molecular levels.

These products have a medium-sized consumer market of around $2 billion in sales per year. They are sold by major drugstores and retailers all over the country, as well as being available for animal use in most vets’ offices. Some scientific studies have called their effectiveness into question, but most studies, as well as experience, show that they provide substantial help to those who take them. As in all scientific studies, a lot depends on their methods and even on their political biases.

For example, a large, double-blind study conducted by the National Institutes of Health in the mid-2000s (called the GAIT study), done at the cost of $12.5 million of taxpayer money, concluded that about 80 percent of the participants with moderate to severe joint pain, and who took glucosamine HCl and chondroitin, got measurable pain relief of 20 percent or more.

Despite this outcome, various publications focused on many other aspects of the study in order to confuse the results. For instance, they pointed to the fact that glucosamine alone is not as effective, which doesn’t matter if one is not selling glucosamine alone. In response, Life Extension Foundation, a medical research and supplement provider in Florida headed by a scrappy doctor named William Faloon, published an article in the June 2006 issue of Life Extension Magazine, citing “sloppy reporting, distorted editorial sensationalism, and conflicts of interest by researchers,” regarding glucosamine and chondroitin studies.

Many other peer-reviewed studies showed the effectiveness of the glucosamine/chondroitin combination. For example, a study that appeared in the journal Military Medicine entitled “Glucosamine, chondroitin and manganese ascorbate for degenerative joint disease of the knee or lower back: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot study,” found that Navy SEALS participating in this study showed average joint pain improvement of about 25-45 percent.

Empirical and scientific studies of animals show the supplement to work in their joints as well, making them far more comfortable and able to move again, even when they have been disabled (and there’s no possible placebo effect with animals). One study entitled “Scintigraphic evaluation of dogs with acute synovitis after treatment with glucosamine HCl and chondroitin sulfate,” which appeared in American Journal of Veterinary Research, found that the supplement helped the dogs make a marked improvement in movement. (Synovitis is inflammation of the “synovial membrane,” which is a layer of connective tissue that lines the cavities of joints and tendons.)

Some doctors have questioned the effectiveness of glucosamine and chondroitin, because not everyone gets the same positive results, for any number of reasons that may not be related to the product. But any time a product is less than 100 percent perfect for 100 percent of the people who use it — essentially all drugs — lawyers will stride into the breach, and get busy looking for “victims” who bought the product and claim that it didn’t work for them. If just one such case is successful (meaning that the lawyers got a big payday), then it lights up the whole plaintiffs’ class action bar to go after every manufacturer and retailer who either made or sold the product.

One such class action case reached a multi-million dollar settlement against Target Stores and Rexall Sundown, the manufacturer of the joint supplement. (More on that case below.) Other retailers such as GNC, Walgreens, Costco, and Rite Aid have all been made defendants in various ongoing lawsuits, along with manufacturers Botanical Labs, Supple, Natrol, and Nutramax Labs, among others. In any class action with damages likely to go over $5 million, jurisdiction is in the federal court system, not in a state court. Since that is where the money is, that’s where the lawyers went.

In the Target/Rexall Sundown class action case, referenced above, the plaintiffs alleged that the labels on the glucosamine/chondroitin product that they bought were not entirely accurate, and thus ran afoul of the Illinois consumer protection statute. No damage to anyone was alleged. No one was harmed by the product. After the lawyers filed suit in the U.S. District Court of Northern Illinois, the parties worked out a settlement, in which the lawyers got $4.5 million in fees and any customer who bought the product got a coupon for $3 toward a new bottle of product, or $5 if they could find the receipt from years ago. In the end, only 30,245 people, out of a potential 12 million, submitted requests for their $3 coupon. The total damages were thus set at $865,000.

After a hearing to approve the settlement, the trial judge cut the lawyers’ fee from $4.5 million to $1.93 million. The appeals court thought this was grossly excessive, noting that if every one of the 12 million consumers who were entitled to make a claim did so against the $865,000 pot of recovery, they would each get only seven cents. Only one-quarter of one percent (.0025) of the eligible number had done so, and because of the small number of claimants, the lawyers were going to get 84 percent of the total money set aside for the settlement.

The class members and defendants were both still unhappy with the large attorney fee, and appealed to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago, Illinois. That court rejected the settlement agreement, describing it as “a selfish deal between class counsel and the defendant [that] dis-serves the class.” The court went on: “But realism requires recognition that probably all that class counsel really care about is their fees.” The court was not done taking the lawyers to the woodshed. A small sampling:

Class counsel shed crocodile tears over Rexall’s misrepresentations, describing them as “demonstrably false,” “consumer fraud,” “false representations,” and so on.... Yet only one-fourth of one percent of these fraud victims will receive even modest compensation, and for a limited period the labels will be changed, in trivial respects unlikely to influence or inform consumers. And for conferring these meager benefits class counsel should receive almost $2 million?

This judgment sent shock waves through the class action lawyer bar. The Seventh Circuit court also exposed another dirty little secret of this type of litigation, namely how the class lawyers worked with the target companies in a mutual alliance that benefited the lawyers and the defendants, to the exclusion of the alleged “victims.”

Here is how it worked: The lawyers on both sides pumped up the anticipated full payout figure, as if every one of the estimated 12 million users of the product was going to make a claim, to some $20 million in damages, and then set the lawyer fee as a percentage of that fictional number. Both sides knew that only a small fraction of the potential claimants would come forward, so this was a sham.

In return for what amounted to paying off the lawyer mob, the defendants got some things they dearly wanted, namely that this settlement would end the litigation without a trial, would stanch further huge paperwork production costs, and would settle the claim forever and for all time, inoculating them against any further lawsuits in that state.

The structure of these small consumer class actions has inherent problems beyond the windfall for attorneys. For example, how will most of the purchasers even hear about the lawsuit and their right to make a claim? How can anyone verify that a particular person actually bought the product? Who saves a small drugstore receipt? In cases involving defects in cars or medical devices, for example, at least it is possible to identify who the members of the class are, since there are records of who bought the products.

The Target/Rexall case also shows why none of these cases ever go to trial. All of the parties gain what they want by agreeing to a settlement, which will be approved in most cases, as long as the lawyers don’t get too greedy, like they did here. But that is the rare exception. Hundreds of these matters just pass on through the alimentary canal of the legal system every year without a hitch.

One manufacturer of these joint health supplements, Nutramax Laboratories, Inc., of Edgewood, Maryland, has been the target of several recent class action suits. (It is also an advertiser in this magazine.) While most companies targeted by these class action suits generally believe it is cheaper to settle than go to court, even when the suit is baseless, Nutramax not only opposes settling baseless suits on principle, but also believes that in the long run, it is better to fight than to cave in to the lawyers.

Several other class action complaints against Nutramax have recently popped up in various places around the country, and Nutramax is contesting each of them. Recently, a special federal court panel consolidated all six into one U.S. District Court in Baltimore, Maryland, for the rest of the pretrial phase, so that production of documents and expert interviews can be done once for everyone, instead of multiple times. Nutramax is holding firm so far — it will not be bullied into a settlement that belies what their research and many studies show — that their products work as claimed and are effective.

Lawyers Running Wild and Defensive Capitalism

How do lawyers get away with picking random business targets, recruiting plaintiffs, and running a shakedown operation for millions of dollars, disguised as a legitimate lawsuit? Is anyone minding the store, other than the isolated Seventh Circuit judge who issued the rare rebuke chronicled earlier? Judges are supposed to approve these class action settlements, but they are lawyers too, and often come to the bench from the same wealthy, prestigious law firms who are seeking the money in their courts. Until the rules of court procedure are changed, no one will be held accountable for these assaults on the productive class.

When judges allow lawyers to run these class action attack operations without reining them in, it is not only unjust, but causes great damage to the system itself, and to public trust in that system. People see the injustice, and the judicial branch’s fundamental lack of fairness and accountability, and they lose confidence in it. As a consequence, the rule of law itself, which is a pillar of our Republic, is imperiled.

It is fair to say that most persons already believe that the legal system is more or less a strange, cruel hoax, and they want as little to do with it as possible. They don’t need to discover this largely hidden legal shakedown operation to affirm that belief. Most people I have met, both inside and outside of courthouses — but especially if they have ever been inside one — regard the judicial branch with contempt, not respect. Hence the joke that it’s the 98 percent of lawyers who make the other two percent look bad.

There is no practical constraint on lawyers who use the class action business model to get rich. There is no fee-shifting rule that would make them pay the legal fees of the target companies if they lose, or to be accountable if they bring a frivolous lawsuit. Only the defendant ends up paying its own massive defense costs, even if the attacker loses. With no consequence for lawyers who bring these suits, even in bad faith, it attracts a lot of participants to the field, and intensifies their foraging for new business segments or products to attack. No one running a medium- or large-sized business is safe from the sudden lawsuit falling out of the sky on them with no warning.

So, businesses will continue to practice “defensive capitalism.” The risk that their companies could be hit with expensive litigation and payoffs must be factored into their business decisions and the price of their products. Have you looked at all of the “caution” stickers on the ladder in your garage, or the ridiculous warning label on your hair dryer, telling you not to stand in bath water while using it?

As a result, persons who could have been employees of these firms suffer, since the firms have not expanded or created more jobs. Stockholders and pensioners suffer from lower profits. Society is deprived of innovative products to benefit our lives, since the cost of innovation and insurance has increased. All of these detriments occur because lawyers run wild, and are permitted to ruin the predictability of our legal system.

The fixes for this injustice are simple. The most basic change would be to level the playing field so it is fair to both parties in a legal case. Change the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which is the procedural manual used by all federal courts, to require attorneys who bring bad-faith civil class action lawsuits to pay the costs incurred by the defendant-target, and it would cut down their number drastically almost overnight. State procedural court rules about class actions should be similarly changed.

When a legal complaint contains a multi-million dollar class action claim about a product that the plaintiff never bought, as happened in two of the Nutramax lawsuits, that is either gross negligence or pure bad faith, and the defense should not have to endure legal fees to oppose it. As long as chasing that huge class action “exit payment” has no downside, there will always be hungry barristers lining up their sights on their next targets.