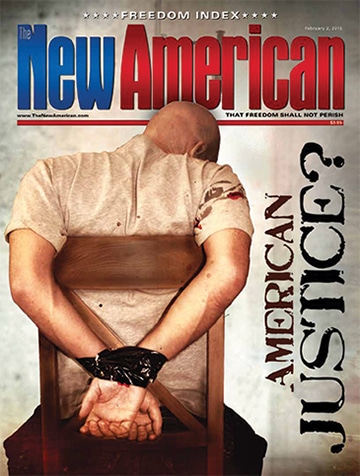

American Justice?

In his timeless essay On Crimes and Punishments — a work greatly admired by the American Founding Fathers — Italian jurist and philosopher Cesare Beccaria condemned torture with unassailable logic:

No man can be judged a criminal until he be found guilty; nor can society take from him the public protection, until it have been proved that he has violated the conditions on which it was granted. What right, then ... can authorize the punishment of a citizen, so long as there remains any doubt of his guilt?... If guilty, he should only suffer the punishment ordained by the laws, and torture becomes useless, as his confession is unnecessary. If he be not guilty, you torture the innocent; for, in the eye of the law, every man is innocent, whose crime has not been proved. Besides, it is confounding all relations, to expect that a man should be both the accuser and accused; and that pain should be the test of truth, as if truth resided in the muscles and fibers of a wretch in torture. By this method, the robust will escape, and the feeble be condemned. These are the inconveniences of this pretended test of truth, worthy only of a cannibal; and which the Romans, in many respects barbarous, and whose savage virtue has been too much admired, reserved for the slaves alone.

It is because of Beccaria’s influence that the U.S. Constitution contains protections against self-incrimination and against cruel and unusual punishment — and, by implication, torture. As Montesquieu famously proclaimed, “Every punishment which does not arise from absolute necessity is tyrannical.” Torture, whether to extract information, serve as a deterrent, or even (as was once fashionable to believe) to purify the condemned from the stain of their transgressions, is not only the very embodiment of tyranny, but also ineffective and immoral. That the United States of America has begun to justify various forms of torture and summary execution without due process is a dire indication of just how far down the road to serfdom we have gone — and what awaits us if we do not soon reverse course.

They Suffered

On December 9, 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a shocking 6,000-page report detailing the systematic abuse of “terror detainees” (including “high-value” detainees, such as Abu Zubaydah and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, linked directly with the planning of the 9/11 terror attacks). Among the report’s more disturbing claims:

• Prisoners were violently “force-fed” rectally, leading to significant tissue damage and other complications.

• One prisoner was killed in November 2002 by hypothermia as a result of being deliberately exposed to the cold for long durations.

• Some prisoners with severe leg injuries, including broken bones and even amputations, were forced to stand on their injured limbs.

• Detainees were systematically subjected to the sadistic practice of “waterboarding,” or simulated drowning, which resulted in several prisoners nearly dying or becoming unresponsive.

• In one instance, a prisoner was subjected to ice water baths and then deprived of sleep for 66 hours by being required to remain standing (it was later determined that this prisoner had been detained by mistake, and was innocent of involvement in terrorism).

• Prisoners were subjected to constant “white noise” and shackled to walls in darkness and filth under conditions that a Federal Bureau of Prisons report characterized as inhumane.

• Prisoners and their families were threatened with death and rape.

• At least 26 of the detainees were innocent of terrorist activities, but many of them were tortured anyway.

Of the 119 detainees documented in the report, at least 39 were subjected to inhumane treatment of various types — and it is worth adding that these are only the instances that we know about. Most of the mistreatment was carried out by the CIA at sites far beyond the borders of the United States, where, sadly, the long arm of American justice (and constitutional guarantees of due process) has little effect. The report also documented numerous instances of CIA officials lying to Congress about whether certain abuses were taking place and the effectiveness of techniques such as waterboarding.

Although Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) took pains to show a measure of bipartisan support for the “torture report” by inviting Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) to speak on behalf of the measure (McCain did, invoking his own experience with torture as a POW in North Vietnam), its release ignited a firestorm of angry denials and recriminations from all sides. The CIA, naturally enough, accused those involved in the production and release of the report of misrepresenting the facts, of exaggerating aspects of prisoner mistreatment, and of jeopardizing national security by publicizing sensitive information — talking points that were largely echoed by Republican partisans who perceived the report as an attack on George W. Bush. Many Democrats, for their part, were embarrassed by the report’s frankness, and fretted about whether the American public would be sympathetic. The American people, meanwhile, were and remain deeply divided over what took place in secret during the early years of the War on Terrorism, when America “disappeared” its enemies into frightening “dark sites,” holding them indefinitely while inflicting horrific torments on them.

What Else Do You Call It?

The often acrimonious debate over the Senate torture report has turned on four points of disagreement: 1) Was it torture, 2) was it effective, 3) was it legal, and 4) was it morally defensible? As to the first, unconditional defenders of the regime have coined a euphemism: “enhanced interrogation.” The word “torture” evoking as it does such unpleasant images, we are now told that the mere inflicting of pain, terror, or humiliation on prisoners does not rise to the level of torture. That was something practiced by our uncouth ancestors, and involved sharp edges, burning brands, and fiendish medieval contrivances such as the rack and the iron maiden. Maybe torture is still carried out by grubby dictators and lawless secret police in remotest Tartary, but not by civilized men in suits who testify before microphones in stodgy Senate hearings. This, at least, is what we are now being conditioned to accept.

But the sly introduction of innocuous-sounding new terminology to cloak horrific realities is a feature of lying politicians in every age. This George Orwell made clear long ago in his timeless essay “Politics and the English Language,” penned at roughly the same time as his two best-known works, the novels Animal Farm and 1984. While some of the issues Orwell invoked have changed, the cadences of politicized English as he characterized it more than 60 years ago are very familiar:

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.

To this Orwell, were he alive, might add another euphemism. Alleged enemy combatants, some of them innocent of any wrongdoing, are immured in foreign prisons; deprived of sleep, food, and water; threatened with murder and rapine by their captors; left naked to freeze outdoors; tormented by being forced to stand for hours on injured limbs; subjected to simulated drowning that in some instances left them unresponsive; and denied any semblance of due process or protection under the Geneva Convention: This is called enhanced interrogation.

By such verbal sleight-of-hand has our government managed to move the markers on what is and is not henceforth to be regarded as humane, licit treatment of prisoners. And a large number of Americans, sadly, seem to have no problem with that.

Of course such practices, were they visited upon American citizens in prisons and jails on American soil, would likely meet with widespread condemnation. But a very grievous precedent has been set, and if not overturned, will be the basis for more of the same — sooner or later, on American soil. And when American prisons and detention centers begin employing “enhanced interrogation” techniques — to find members of domestic terror cells or to winkle out their nefarious plans, for instance — it will matter little what we choose to call it.

Reason for Being

It has long been understood by rational minds such as Beccaria and the Founders that — no matter how compelling the rationale — torture, legal or illegal, has never been particularly effective. Wrote Beccaria:

Every act of the will is invariably in proportion to the force of the impression on our senses. The impression of pain, then, may increase to such a degree, that, occupying the mind entirely, it will compel the sufferer to use the shortest method of freeing himself from torment. His answer, therefore, will be an effect as necessary as that of fire or boiling water; and he will accuse himself of crimes of which he is innocent. So that the very means employed to distinguish the innocent from the guilty, will most effectually destroy all difference between them.

It would be superfluous to confirm these reflections by examples of innocent persons, who, from the agony of torture, have confessed themselves guilty: innumerable instances may be found in all nations, and in every age. How amazing that mankind have always neglected to draw the natural conclusion!

Men under torture will sometimes even seek to incriminate their personal enemies or people they simply dislike, leading to the mistreatment of innocents. Of course, most of the 119 “detainees” (note that the media refrain from calling them “prisoners of war,” perhaps because a legal state of war with respect to various bands of terrorists does not and indeed cannot exist) are not “innocent”; they are “the worst of the worst” and undeserving of our sympathy. Such, at least, is the argument of the CIA and all who support such atrocities. But this line of argument neglects the most important principle in Anglo-American judicial theory, that, in the eyes of the law (and therefore, the government), every man is presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law. In recent history, that mantle of protection has covered “the worst of the worst,” including serial killers, mass murderers, rapists, purveyors of child pornography, and those who molest and kill innocent children. It has also included notorious domestic terrorists such as Timothy McVeigh and Ramzi Yousef, men demonstrably connected with terror cells that quite possibly were capable of additional attacks had not many of their members been apprehended. All of these, and thousands of other miscreants of their ilk, have been accorded due process and spared the agonies of torture, despite in many cases committing heinous crimes that took many lives or inflicted terrible suffering on many people.

Yet in the years since 9/11, America’s attitude toward such people has hardened, and the notion that tortured detainees suspected of terrorist activity “deserved what they got” is receiving more and more currency. As it does, America slides more and more into lawlessness, for a nation that will not uphold the rule of law for “the worst of the worst” has by definition created a punitive caste — be they police, military, or gestapo — deemed to be above the law, and empowered to mete out summary justice in the name of public safety.

Principles of jurisprudence aside, Americans enjoy robust constitutional protections against torture, both explicitly (the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” — note that even if “waterboarding” is not deemed to be cruel, it is certainly unusual!) and implicitly (the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination and requirement of due process; this amendment also enumerates the three broad classes of admissible punishment, namely, deprivation of “life, liberty, or property”; torture is not any of these).

But, some have insisted, terror detainees have no rights under the American judicial system because they aren’t American citizens and because the Bill of Rights doesn’t apply to prisoners of war. If that were true — if the perpetrators of “enhanced interrogation” believed it to be true, in any event — then why aren’t these prisoners brought back to the United States and interned in prisoner of war camps, as was done with captured Germans and Japanese during the Second World War? Why, instead, are they kept squirreled away on Navy ships or in overseas facilities such as Gitmo on Cuban soil, denied access to counsel, and kept in legal limbo? Because, of course, prisoners of war and so-called war criminals — however heinous their alleged crimes — do have rights, as recognized under the Geneva Convention. In particular, Common Article 3 of that body of treaty law — to which the United States is a signatory, prohibits, among other things: “Violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture”; “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment”; and “the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.” This last point is a defense of what we call due process, and is as much to say that terror detainees or any other prisoners of war cannot be summarily or secretly put to death because of the inconveniences involved in granting them due process.

Legal minds in the CIA, the military, and the Justice Department are well aware of these prohibitions — as well as of the fact that the U.S. government has chosen to flout them. They know that, should the likes of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed ever be brought to the United States to stand trial, he would stand a fair chance of getting off, given the fact that his basic human rights have been so flagrantly violated. As a result, Mohammed and many others are in permanent legal limbo, with the U.S. government intending on keeping them detained until they die of natural (or unnatural) causes, thus sparing the feds the inconvenience of obeying the law.

As to the morality of such practices, the most popular justification is that the inhuman monsters who gave us 9/11 deserve no sympathy or mercy, inasmuch as they gave none to their thousands of victims. In the first place, only a very few of the terror detainees were involved with 9/11; most of them got swept up in the heat of war after the United States invaded Afghanistan, and thus are guilty of little more than being enemy combatants. But even were they all hardened terrorists with American blood on their hands, like Abu Zubaydah and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, they remain human beings and children of God, and are thus entitled to be treated as such by a nation that professes Christian heritage. Jesus of Nazareth warned His followers that retributive justice — the principle of “an eye for an eye” or lex talionis — was a characteristic of fallen Babylon, not a Christian people. It was because of such teachings that Western law evolved to afford maximum possible dignity and protection to all individuals (in stark contrast, we might add, to the sort of justice characteristically meted out in Islamic nations such as Saudi Arabia) before the state brought to bear the awful machinery of justice in punishing criminality. As English jurist Sir William Blackstone pointed out long ago, the proper purpose of man-made justice is not to substitute for the judgments of Almighty God, but to protect society from criminal depredations.

Unfortunately, as America drifts further and further from her Judeo-Christian moorings, arbitrary, vengeful government action against wrongdoers becomes more and more attractive, as people are seen less and less as children of God equal in His eyes and more and more as mere animals to be herded, exploited, and culled at the whim of the state. The acceptance of torture is only part of a larger mindset that tends to dehumanize the children of God when the divine origins of man are no longer accepted.

Disappearing Rights

Beccaria believed that the origins of many forms of torture were religious, harkening from a day when church and state were united in a mission to purge humanity of its transgressions. For the modern secular state, however, arbitrary, lawless official violence, including torture, has become a sort of sacrament, proof that the state’s punitive powers are unlimited and unassailable. The same mindset that approves of the torture of prisoners of war has led to the militarization of America’s police forces; it is no coincidence that the appalling rise of thuggish behavior by domestic law enforcement has come about at the same time and in the same political climate that has accepted certain forms of torture. The use of Tasers, now routinely justified by law enforcement even against the elderly, the infirm, and the mentally ill, has become widely accepted (as recently as 1993, the crime comedy Undercover Blues portrays the Taser as an exotic instrument of torture, used in the movie not by law enforcement but by international criminals to subdue and kidnap one of the protagonists). Yet Tasers are extremely painful and have sometimes proven fatal. They are used not only on the street to apprehend suspects, but also to force compliance in jails and prisons. The use of such devices is similar to, if not indeed, a form of torture; certainly it constitutes punishment of a sort for crimes not yet proven in a court of law. And the symbolism of the Taser is unmistakable; just as cattle and other livestock are herded and controlled with electric prods, so too are human “herds” now kept in compliance by the creative application of painful electric shocks.

As for America’s ongoing prosecution of the War on Terrorism, the Obama administration may claim to have discontinued practices such as waterboarding and other of the more inhumane practices detailed in the torture report, but its hands are by no means unsullied. The use of drones to assassinate alleged terrorists overseas is another instance of the arbitrary use of force, in this case lethal force, without due process. All of the arguments on behalf of the use of drones are the same as those favoring torture, and all of them fail for the same reasons (recall that the Geneva Convention, Common Article 3, prohibits “the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples”).

Within living memory, it was fashionable for political and military leaders to assert that America (including the CIA) did not carry out assassinations. While such asseverations were doubtless untrue even decades ago, at least the official sunlight policy was to deny that they took place and that America’s values precluded such policies. Today’s America openly assassinates foreigners identified as enemies of the state. In one case, an innocent teenage boy and American citizen (Abdulrahman al-Awlaki) was killed in a drone strike in Yemen only weeks after his father Anwar al-Awlaki, also an American citizen, was similarly dispatched. Both of these people were executed without due process, and the same can be said for the hundreds of others — including countless wives, children, and other innocent bystanders — who have perished in America’s semi-secret “drone war” in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen. The use of armed drones on the battlefield is one thing; the systematic deployment of such weapons against civilians, including houses and wedding parties, is quite another.

And, as with torture, the use of drones against Americans on American soil may only be a matter of time, given the popularity with law enforcement of unarmed drones as surveillance devices. “Officer safety” being paramount in law-enforcement circles these days, it isn’t at all difficult to imagine a day when armed drones are used for crowd control, for instance. It might start with drone-administered tear gas and rubber bullets, but lethal antipersonnel drones might eventually become as standard as the APCs, grenade launchers, and other surplus military hardware now being scooped up by domestic law enforcement at the behest of Homeland Security.

All this and more might be in the near future, unless we reverse America’s rush to militarize law enforcement and to stamp out terrorism regardless of the cost in civil liberties. Our country was founded on the principle of the dignity and liberty of every individual, and there was a time when only a small minority of Americans was eager to trade liberty for the illusion of security. Now, unfortunately, many seem indifferent to the dangerous precedent being set by torturing, imprisoning, and killing foreigners (and a few American citizens, such as the al-Awlakis) without any semblance of due process. What will happen when the federal government, which everywhere sees challenges to its authority and threats to its power, decides that its greatest enemy is not terrorists abroad but its own fed-up citizens?

This article is an example of the exclusive content that's available only by subscribing to our print magazine.