People of Massachusetts when your country shall be cultivated, adorned like this country and ye shall become elegant, refined in civil life, then, if not before, ‘ware your liberties.”— Thomas Hollis’ note accompanying a shipment of books to Harvard College

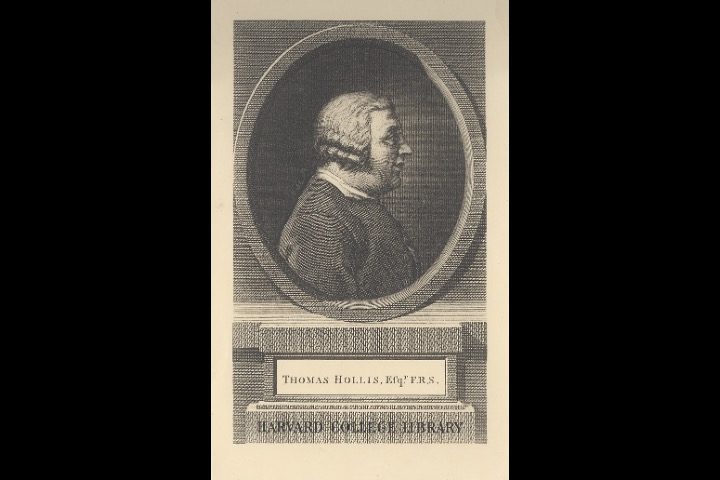

In the annals of history, the name Thomas Hollis may not be as familiar as those of the luminaries of the Enlightenment or the founding fathers of nations. Yet, his impact on the ideological underpinnings of modern republican and libertarian thought, as well as his contributions to the arts and education, renders him a figure of profound significance. Thomas Hollis (1720-1774) was an English political philosopher and philanthropist whose legacy, though subtle, has been instrumental in shaping the contours of liberal democracy and academic freedom.

Hollis was born into a family of prosperous merchants. It was not his commercial acumen that would define his legacy, however, but his unwavering commitment to the principles of liberty, freedom of speech, and the advancement of knowledge. He was deeply influenced by the writings of Algernon Sidney, John Locke, Henry Neville, and other Enlightenment thinkers whose ideas about natural rights and the right of the people to choose their own form of government laid the groundwork for modern representative governance.

Hollis’ Career and Philosophical Contributions

Hollis’ career was not marked by political office or public notoriety. Instead, he chose to exert his influence through strategic philanthropy, focusing on the dissemination of ideas that would foster a society based on reason, virtue, and individual liberty. He was an ardent supporter of civil liberties, and opposed to any form of tyranny, which he saw as the greatest threat to human progress. His efforts were primarily channeled into supporting writers, thinkers, and institutions that aligned with his philosophical outlook.

One of Hollis’ most significant contributions was his role in the dissemination of republican and so-called Whig ideas. He financed the publication of key works by John Locke, Algernon Sidney, and other proponents of republican thought, ensuring their availability at a time when such ideas were often suppressed. Hollis understood the power of the printed word in shaping public opinion, and was instrumental in creating an intellectual milieu that would eventually lead to revolutionary changes in both America and Europe.

For example, Algernon Sidney’s advocacy for liberty and his ultimate execution for alleged conspiracy against King Charles II made his writings emblematic of the struggle against tyranny.

Understanding the transformative potential of Sidney’s ideas, Thomas Hollis took it upon himself to ensure that these notions of individual sovereignty and liberty were accessible to the American public. He facilitated the publication of Sidney’s works in the Colonies, believing that these texts would inspire and inform the burgeoning republican sentiment among the American populace. His efforts were not merely acts of philanthropy, but strategic interventions aimed at nurturing the philosophical underpinnings of what would become the United States.

The distribution of Sidney’s works in America, championed by Hollis, played a crucial role in the intellectual development of American revolutionary leaders. Figures such as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams drew inspiration from Sidney’s writings, incorporating his ideas into the fabric of American political thought and discourse.

So powerful was his influence, in fact, the Baptist Reverend Noel Turner wrote of Hollis: “This Hollis, indeed, might be said even to have laid the first train of combustibles for the American explosion.”

Additional evidence of the lasting and immeasurable impact of Hollis’ contribution to the cause of American liberty is found in a 1784 letter from Benjamin Franklin to Brand Hollis, Hollis’ heir. Of the American indebtedness to Hollis’ work, Franklin wrote:

These volumes are a proof of what I have sometimes had occasion to say, in encouraging people to undertake difficult public services, that it is prodigious the quantity of good that may be done by one man, if he will make a business of it. It is equally surprising to think of the very little that is done by many; for such is the general frivolity of the employment and amusements of the rank we call gentlemen that every century may have seen three successions of a set of a thousand each . . . no one of which sets, in the course of their lives, has done the good affected by this man alone. Good, not only to his own nation, and to his contemporaries, but to distant countries, and to late posterity; for such must be the effect of his multiplying and distributing copies of the works of our best English writers on subjects the most important to the welfare of our society.

No less an authority than the esteemed historian Caroline Robbins noted the indelible impression on the Founding Fathers of the books printed, promoted, and provided by Thomas Hollis to American Colonists. Robbins writes:

Hollis had sought out as many editions of the ‘classic Whig writers’ as possible [Milton, Nedham, Vane, Harrington, Neville, Marvell, Sidney, Locke, Molesworth, and Trenchard and Gordon], noting differences between them he edited himself or encouraged editions by others, and at times published in the newspapers important passages from his ‘canonical books.’ All of them broadcast libertarian ideas; all contributed something to the faith proclaimed by the Declaration of Independence not so long after Hollis’ death.

Patronage and Contributions to Education

Hollis’ philanthropy extended beyond the realm of political philosophy. He was a major benefactor of Harvard College, to which he donated a vast collection of books, manuscripts, and artworks aimed at enriching the intellectual life of the institution. These contributions were not merely acts of generosity, but were imbued with a strategic purpose: to cultivate an educated elite grounded in the principles of liberty and equipped to lead their society toward a more enlightened, educated, and virtuous future.

Moreover, Hollis’ endowments to Harvard and other educational institutions were accompanied by specific instructions to promote academic freedom and to ensure that students were exposed to a wide range of ideas. He was a pioneer in the concept of the university as a space for free inquiry and debate, a legacy that continues to influence the ethos of academic institutions around the world.

Impact on the Arts

In addition to his political and educational contributions, Thomas Hollis was a discerning collector and patron of the arts. His collections included works that reflected his political beliefs and philosophical ideals, such as those depicting scenes of liberty and heroism. Through his patronage, Hollis supported artists whose works celebrated the human spirit and its capacity for reason, creativity, and resistance against oppression.

Legacy and Relevance Today

The legacy of Thomas Hollis is not encapsulated in monuments or remembered in popular lore, but it is woven into the fabric of modern democratic societies. His life’s work reminds us of the importance of defending and promoting the principles of liberty, the value of free inquiry in education, and the role of art in inspiring and reflecting societal values.

In an era where these principles are increasingly under threat, the example set by Thomas Hollis serves as a beacon for those committed to preserving the ideals upon which free societies are built. His belief in the power of ideas to transform the world continues to resonate, underscoring the responsibility of individuals and institutions to nurture and protect the fragile edifice of republican government and liberty.

Conclusion

Thomas Hollis was more than a benefactor or philosopher; he was a visionary who understood the profound impact that ideas, education, and art could have on the advancement of society. Through his strategic philanthropy and unwavering commitment to the principles of liberty, he contributed to shaping the intellectual landscape of his time and beyond. As we chart our course around the tyrannical eddies of the 21st century, Hollis’ life, legacy, and literary patronage offer invaluable lessons in the enduring importance of fostering a culture of freedom, faith, and diligent study.