Senator Claiborne Pell (D-R.I.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, rose in the United States Senate on May 12, 1988 to introduce — for himself and Senator Richard Lugar (R-Ind.) — Senate Joint Resolution 317. “The resolution I am introducing today urges the people of the United States to observe the bicentennial of the French Revolution and the historic events of 1789,” said Pell. “The more we learn about the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen,” asserted the powerful solon, “the more we learn about our own past.”

S.J. Res. 317 was quickly passed by both the Senate and the House, and, with President Reagan’s signature, became Public Law 100-482 on October 11, 1988. Not that this legislative flourish was necessary to assure a warm reception for the Revolution’s bicentennial. Everywhere, it seems, there are partisans of Mirabeau, Danton, Marat, and Tallyrand.

Pell’s former Senate colleague, Charles Mathias, is chairman of the American Committee on the French Revolution. Its advisory board boasts an impressive array of American noblesse (David Rockefeller, Stanley Hoffman, J. Walter Annenberg, et al). On July 14th, Bastille Day, the Committee will be hosting celebrations at the Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., and at the Lincoln Center in New York City.

Also on July 14th, United States President George Bush and the leaders of the other major free world powers will convene a summit in Paris to further the already well-advanced plans for establishing a “new international economic order.” The date and place of this palaver of world notables are especially propitious for their purpose, and not at all coincidental. Those who plan such things are fully cognizant of the bloody well from which their present endeavor has sprung, as well as of the power of symbols.

In France, the socialist Mitterrand government, of course, is spending millions of francs on revolutionary posters, festivals, and television and radio programming. “The commemorative ceremonies and other events held throughout 1989,” says Jean-Noel Jeanneney, president of France’s bicentennial commission, “will express … our attachment to the values of democracy and progress bequeathed to us by this Revolution.”

L’Anti-89

Not all Frenchmen sympathize with these revolutionary “values,” and diehard Royalists are not the only ones to oppose the bicentennial celebrations. Organizers of an “Anti-’89” campaign are hoping to draw upwards of a million followers to Paris this summer to pray and demonstrate against the “Satanic, anti-Christian revolution” unleashed in France 200 years ago. The campaign is being promoted and organized largely through the distribution of L’Anti-89, a monthly tabloid published by the Society of Saint Pius X, as well as a series of conferences on the French Revolution sponsored by the Society, which is headed by excommunicated Roman Catholic Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre of Econe, Switzerland.

Although completely ignored by the French and international press, L’Anti-89, launched in 1987, has definitely caught the attention of Mitterrand. With blistering editorials and reprinted accounts of the savage slaughters and vile desecrations of the revolutionists, the publication has taken the government to task for glorifying “one of the most shameful and horrible epochs” in human history. “The government was shocked when we announced plans for one million people on August 15th,” Brother Edward Saurette, a spokesman for L’Anti-89 in Paris, told The New American in a telephone interview. “We don’t know how many people to expect, really, and we would consider 50,000 to be a success; but, on the other hand, we don’t think that 500,000 to one million is an unrealistic expectation.” The plan for August 15th, the Feast of the Assumption in the Catholic liturgical calendar, calls for a massive prayer procession through Paris to the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Although the Anti-89 campaign seems to offer the only organized resistance to the celebrations, other publications — Valeurs Actuelles, Choc, Présent, and Fidelité, for instance — are also taking aim at the bicentennial.

Indeed, it was “the best of times … the worst of times.” 1789 was the fateful year in which, on one side of the Atlantic Ocean, a constitutional Republic was established by honorable, temperate men who acknowledged the sovereignty of Almighty God; and, on the other side, a “Democracy” characterized by the basest tyranny was created by profane creatures who reviled Heaven.

Various theories have been advanced concerning the causes of the French Revolution — “famine and the grinding poverty of the peasants,” “the influences of Voltaire, Rousseau and the Encyclopaedists,” “the unbearable oppression of the Ancient Regime,” “excessive taxation and feudal privilege,” “the economic bankruptcy of the Crown” — all specious. “The practice of attributing the revolution to such causes, as though a quasi-physical law had been operating which necessitated that effect (revolution), is a grave error,” observes Rev. Clarence Kelly in his book Conspiracy Against God And Man. “To the extent that such conditions did exist, one cannot say that the revolution was a necessary consequence. If economic problems and despotism necessarily cause revolution, then surely no Communist regime would stand long.”

By the standards of the day, France under the Bourbon monarchy was anything but “backward,” “impoverished,” or “oppressive.” As the premier power of Europe, France was the largest, wealthiest, most populous nation on the continent, with a well-developed middle class, and a strong agricultural, industrial, and foreign trade base. In science, literature, and culture France led the world. According to all the most credible accounts by contemporary travelers, France was the place to live in the 18th Century, whatever one’s station in life.

In The French Revolution, the late Nesta H. Webster cited both impartial and pro-revolutionary witnesses whose testimony puts the lie to the “starving peasant uprising” arguments. An Englishman named Dr. Rigby, for instance, wrote to his wife from France during the summer of 1789: “The general appearance of the people is different to what I expected; they are strong and well-made…. Everything we see bears the marks of industry, and all the people look happy…. We have seen few of the lower classes in rags, idleness and misery. What strange prejudices we are apt to take regarding foreigners!”

A far different aspect greeted the good doctor when he entered Prussia: “There was a gloom and an appearance of disease in almost every man’s face we saw; their persons also looked filthy. The state of wretchedness in which they live seems to deprive them of every power of exertion.” Rigby was struck by the comparative vitality of France: “How every country and every people we have seen since we left France sink in comparison with that animated country!”

Thomas Jefferson, after extensive excursions throughout the French countryside and a close examination of agricultural practices there, was pleasantly surprised to find that the conditions of the peasants were far better than he had been led to believe. “I have been pleased to find among the people a less degree of physical misery than I had expected,” Jefferson wrote to Lafayette in 1787. “They are generally well clothed, and have plenty of food, not animal indeed, but vegetable, which is as wholesome.”

Even the celebrated Marxist historian Georges Lefebvre, president of the Société des Etudes Robespierristes and editor of the Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française, noted in The Great Fear of 1789 that the “agrarian crisis would have been acute indeed if the farming system [in France] had not been far more favorable to the peasants than anywhere else in Europe.”

Savior of the Public Liberty

Far from having been the cruel despot he is often portrayed as, Louis XVI was a well-intentioned, though often weak and inept, monarch thrust into circumstances beyond the measure, perhaps, of even the wisest and most adroit ruler. A devout Christian eager to improve the plight of his subjects, he launched a serious program of reform in the first year of his reign. In the decade and a half leading up to 1789 he had abolished torture and all forms of servitude in his domain, granted liberty of conscience to Protestant sects, reformed the prisons and hospitals, and proposed the abolition of the salt tax and lettres de cachet (arrest warrants that permitted imprisonment without trial).

Louis XVI had undertaken these genuine reform efforts on his own initiative, without compulsion. In fact, it was the French Parliament that obstructed many needed reforms. There is no evidence that the French people had entertained any notion of overthrowing the Crown.

Prior to convening the Estates General, the King had called for cahiers de doleances, or lists of grievances, to be drawn up and sent in from all the provinces, to aid in the process of reform. According to 1789, published by American Opinion, “Not one [cahier] contemplates the abolition of the monarchy. Not even the petition presented by the City of Paris, for all its obstreperous demands and radical animosity, would dare to suggest such a profound upturning of the national constitution. ‘The person of the monarch is sacred and inviolable,’ says the memorandum…. Religion is praised as a necessary condition of man. The object of law is to safeguard liberty and property. The commissioners would like the Bastille torn down, and a noble column erected on the site bearing the inscription, ‘To Louis XVI, Savior of the Public Liberty.’”

The Bourbon monarch was also most tolerant of dissent. “Paris had more printers, bookstalls, book dealers, journalists, and theorists than any city had ever before seen,” records historian Otto Scott in his biography of Robespierre. “Censorship was still on the books but no longer enforced….”

It was Louis XVI’s liberal tolerance toward the champions of so-called “enlightenment” and “reason” that undermined both Church and Crown. While, in the main, the French people — particularly the peasants and working people — remained staunchly Christian and monarchist, the disaffected nobility and the habitués of the intellectual salons gave sway to libertine passions and head, “new” doctrines. Of the decade preceding the revolution Scott writes:

Strange cults appeared; sex rituals, black magic, Satanism. Perversion became not only acceptable but fashionable. Homosexuals held public balls to which heterosexuals were invited and the police guarded their carriages. Prostitutes were admired; swindles and sharp business practices increased. Political clubs of the more radical sort proliferated. The Freemasons, whose lodges ranged from the sedate to the wild-eyed, extended across the nation. There were hundreds of such lodges in Paris alone, and thousands throughout the country. The air grew thick with plans to restructure and reconstruct all traditional French society and institutions.

“The press, for the first time in history, was the spearhead, font and fuel for these discussions,” writes Scott. The journals of that day, like so many now, “were mixtures of politics and smut. They admired agitators extravagantly and never discussed the Church without mention of scandal nor government without criticism. They relied heavily on tales of sin in high places and highhanded outrages of the Court.”

In his Paris in the Terror, Stanley Loomis notes the irony that “of all countries in Europe, France was the only one that could have had a revolution — not because she groaned under the lash of tyranny, but on the contrary, because she tolerated and even invited every conceivable dissension. Restlessness, a passion for novelty and the pursuit of excitement were everywhere in the air. They were the fruits of idleness and leisure, not of poverty.”

It is true that the French treasury was in desperate straits, but that condition was not simply the result of Court extravagance, as is often asserted. In her first years as queen, Marie Antoinette established a reputation as an insatiable spendthrift with a taste for lavish soirées. But historians have documented the rapid maturing of her character and her development of simpler tastes when she became a mother.

When Louis XVI ascended to the throne, the French government was spending 235 million francs a year and had revenues of only 213.4 million francs. He attempted to remedy the deficit inherited from his grandfather, Louis XV, but, being untrained in economics, left the management of the treasury up to others. Unfortunately, his finance ministers — Necker, Calonne, Brienne, and Necker again — attempted to create the impression of prosperity by juggling the books, launching massive welfare and public works projects, taking out new loans, and padding their own accounts.

Details about the finances of the government in pre-revolutionary France are recorded in the book 1789:

In 1789, only six percent of the national revenue was budgeted for the entire expense of the Court; and only a small fraction of that went for personal needs. Army, Navy and diplomacy ate up twenty-five percent. And fifty percent — mark that, fifty percent — went for debt services on that four and one-half billion national debt…. And what was the single biggest cause of the debt? Two-thirds of the debt, three billion livres, had been spent to support the United States in the American Revolutionary War.

Yes, it was “wicked” King Louis — not the revolutionary Jacobins — aided the American colonists in their struggle against King George. It is also worth remembering, in this year of our bicentennial, that our nation was barely founded when the Jacobins sent their agents (most notably, Citizen Genet) here to establish subversive “Democratic Clubs” and topple our infant republic.

Louis the Sixteenth, at the beginning of 1789, was faced with many problems, but “the people” were not one of them. “The masses remained pious,” Will and Ariel Durant point out in Rousseau and Revolution, “but their leaders had lost respect for priests and kings; the masses loved Louis XVI to the end, but the leaders cut off his head.” Even the king’s enemies conceded that he was a benign ruler. Frederick II of Prussia (dubbed “the Great” by Voltaire), who conspired with Mirabeau and the Orleanistes to depose Louis, wrote to d’Alembert: “You have a very good king…. A king who is wise and virtuous is more to be feared by his rivals than a prince who has only courage.” D’Alembert replied: “He loves goodness, justice, economy, and peace…. He is just what we ought to desire as our king, if a propitious fate had not given him to us.” Voltaire also agreed: “All that Louis has done since his accession has endeared him to France.”

If the people of France loved their king, enjoyed a higher standard of living than most others on the continent, and had every prospect of improving their lot in life with a reform-minded ruler, why then did they revolt? The answer, of course, is that the revolution, from the fall of the Bastille to the accession of Napoleon, was never a movement of “the people.”

Citizens of Paris witnessed the mysterious arrival of thousands of frightful strangers in their midst in the spring of 1789. In The French Revolution, Nesta Webster painstakingly reconstructed the scene from primary sources:

Towards the end of April the peaceful citizens saw with bewilderment bands of ragged men of horrible appearance, armed with thick knotted sticks, flocking through the barriers into the city. This sinister contingent is not, as certain historians would have us believe, to be confused with the former crowds of peasants — “they were neither workmen nor peasants,” says Madame Vigee le Brun, “they seemed to belong to no class unless that of bandits, so terrifying were their faces,” and Montjoie adds that this aspect was intentional — “they had been instructed to disfigure their faces in a manner so hideous that they were objects of horror to all the Parisians.” Other contemporaries, whose accounts exactly coincide with the foregoing, add that these men were “foreigners” — “they spoke a strange tongue….” Marmontel describes them as “Marseillais … men of rapine and carnage, thirsting for blood and booty, who, mingling with the people, inspired them with their own ferocity.”

These “brigands” and “bandits,” referred to in so many of the accounts of the day, had been brought to the city in the employ of Louis Philippe, the Duc d’Orleans. By various estimates they numbered between 20,000 and 40,000. The immensely wealthy and powerful duke harbored intense hatred for his cousin, Louis XVI, and his lust for the throne was transparent. He was as dissolute and amoral as the king was sober and virtuous. Grand Master of all Grand Orient Lodges of Freemasonry, he had an unequalled network for communications, intelligence, and propaganda.

What Really Happened

During the summer of 1789 the Duc d’Orleans’ murderous brigands terrorized Paris and created a famine by commandeering and/or destroying shipments of grain coming into the city. Other agents of the duke bought up grain supplies and held them off the market. Still other Orleaniste agents “buffeted the populace with calamitous rumors: that economic collapse was imminent; that the king’s troops were massacring citizens in various parts of the city; that the king had mined the Assembly to blow up the legislators; that the bread and wine had been poisoned.

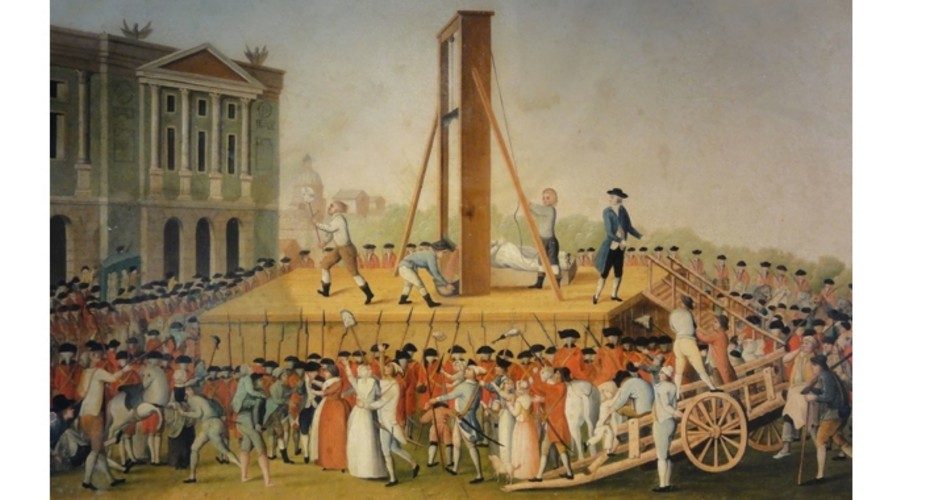

In this highly agitated state the Orleanistes succeeded, on July 14th, in rousing a mob of about 1,000 to march on the Bastille — not to free prisoners, nor destroy a hated symbol, but to acquire the arms stored there so as to defend themselves, against both the brigands and the troops that were reported to be advancing. The Bastille, an ancient and little-used fortress-prison, was scheduled to be demolished. It was guarded only by a small contingent of old army veterans and Swiss Guard, but with fifteen cannon they had more than enough fire-power to disperse the mob.

The commander of the fort, Governor De Launay, couldn’t bring himself to fire on his own countrymen. Bearing in mind the king’s aversion to violence, he allowed his men to put up only token resistance before he surrendered to the mob. For this humane gesture, he paid with his life. Although the decent Parisians duped into this exercise tried to protect him, the brigands overpowered them, butchered De Launay, and paraded through Paris with his head on a pike. Thus began the revolution.

And what of all the hapless prisoners in the Bastille’s dungeons? The Bastille, Webster notes, held only seven — “four forgers, Bechade, Lacaurege, Pujade, and Laroche; two lunatics, Tavernier and De Whyte, who were mad before they were imprisoned, and the Comte de Solages, incarcerated for ‘monstrous crimes’ at the request of his family.”

The following day, the Orleaniste brigands “arrested” Berthier de Sauvigny, the Intendant of Paris, at Compiegne, where he was supervising the transport of grain and flour to Paris. His energetic efforts to provide food for the city were upsetting the planned famine and had to be stopped. He was denounced as a “hoarder of grain” and sentenced to die. “Thereupon ‘a monster of ferocity, a cannibal,’ tore out his heart,” Webster recounts, “and Desnot, the ‘cook out of place’ who had cut off the head of De Launay and again ‘happened’ to be on the spot, carried it to the Palais Royal. This ghastly trophy, together with the victim’s head, was placed in the middle of the supper-table around which the brigands feasted.”

Still worse atrocities would follow, with the encouragement and direction of the leaders of the Revolution.

Ignoring the abundant evidence to the contrary, the editors of Life magazine, in a series of articles in 1969 on the subject of revolution, wrote: “The French Revolution was not planned and instigated by conspirators. It was the result of a spontaneous uprising by the masses of the French people….” So the lie continues, though more honest and reasonable minds oppose and expose it. “The French Revolution did not occur spontaneously,” answers Clarence Kelly. “Yet though we must acknowledge the period of development that led up to these events, it is evident that they did not have to come about. They happened because men armed with a plan intervened and gave direction.”

In his “Essay On The French Revolution,” English historian Lord Acton perceptively observed: “Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. The managers remain studiously concealed and masked, but there is no doubt about their presence from the first.”

In her Secret Societies and Subversive Movements, Nesta Webster concurred: “But for this co-ordination of methods the philosophers and Encyclopaedists might have gone on forever inveighing against thrones and altars, the Martinistes evoking spirits…. [I]t was not until the emissaries of Weishaupt formed an alliance with the Orleaniste leaders that vague subversive theory became active revolution.”

The Illuminati

These “emissaries of Weishaupt” were members of the secret Order of the Illuminati, a conspiratorial cabal formed in Bavaria on May 1, 1776, by Adam Weishaupt, a professor of canon law at Ingolstadt University. According to the Baron Adolph von Knigge, one of Weishaupt’s top apostles, who broke with the Order in 1784, the aim of the Illuminati was to abolish Christianity, and all the governments of Europe, and to establish a great world government under the direction of the Order.

Toward that end, the conspirators employed any and all means: bribery, theft, assassination, seduction, blackmail, sedition, slander, and the instigation of riots, revolutions, and wars. Weishaupt’s favorite maxim was, “The end justifies the means.” His scheme took a great leap forward in 1782 at the great convention of continental Freemasonry in Wilhelmsbad, Germany when his agents succeeded in bringing the Masonic lodges under the control of the Order.

Weishaupt’s sinister cabal was discovered and the Order’s archives, with numerous incriminating documents, seized by the Bavarian authorities in 1786. In addition, four members of the secret organization came forward with testimony to confirm the evil intent of the Illuminati. As a result, the Order was outlawed and Weishaupt and his co-conspirators banished. That action only served to speed the dissemination of the group throughout Europe.

The Jacobin Clubs

In his 1798 classic, Proofs of a Conspiracy, Dr. John Robison, the distinguished scientist, Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University, Scotland, and the leading contemporary English-speaking authority on the “terrible sect,” said this of the Illuminati’s operations in France during the revolutionary period: “I have seen this Association [the Order of the Illuminati] exerting itself zealously and systematically, till it has become almost irresistible: And I have seen that most active leaders in the French Revolution were members of this Association, and conducted their first Movements … by means of its instructions and assistance….”

The Illuminati’s primary agent in France was Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti Comte de Mirabeau, a reprobate and conspirator of the first degree. Together with the Duc d’Orleans, he assembled a force of frightful power and ferocity. The Jacobin clubs became their principal tool for terror and political machinations.

From Mirabeau’s own pen we see the unmistakable Illuminist imprint. On October 6, 1789 a manuscript of Mirabeau’s was found among others seized at the home of his publisher. It is pure Weishaupt. Besides his nihilistic fury, it is particularly noteworthy for his open contempt for “the people” he claims to champion:

We must overthrow all order, suppress all laws, annul all power and leave the people in anarchy…. We must caress their vanity, flatter their hopes, promise them happiness after our work has been in operation…. But as the people are a lever which legislators can move at their will, we must necessarily use them as a support, and render hateful to them everything we wish to destroy and sow illusions in their paths.

The clergy, being the most powerful through public opinion, can only be destroyed by ridiculing religion, rendering its ministers odious, and only by representing them as hypocritical monsters…. Libels must at every moment show fresh traces of hatred against the clergy. To exaggerate their riches, to make the sins of an individual appear to be common to all, to attribute to them all vices; calumny, murder, irreligion, sacrilege, all is permitted in times of revolution.

Mirabeau continued: “What matters the victims and their numbers? Spoliations, destruction, burnings, and all the necessary effects of a revolution? Nothing must be sacred and we can say with Machiavelli: ‘What matter the means as long as one arrives at the end?’”

His utter ruthlessness shocked even his revolutionary colleagues. Pierre Malouet wrote in his memoirs: “Mirabeau was, perhaps, the only man in the Assembly who saw the Revolution from the first in its true spirit, that of total subversion.”

But there were others who also saw “its true spirit.” The horrors that were planned for France caused Mirabeau’s one-time friend and fellow Illuminatus, the Marquis de Luchet, to recoil in terror. He determined to warn the unsuspecting victims of the impending onslaught, publishing in January 1789 his Essay on the Sect of the Illuminati. De Luchet’s pamphlet, published months before the fall of the Bastille, is a vital document almost completely ignored by historians. It proved prophetically accurate:

Deluded people! You must understand that there exists a conspiracy in favor of despotism, and against liberty, of incapacity against talent, of vice against virtue, of ignorance against light! It is formed in the depths of the most impenetrable darkness, a society of new creatures who know each other without being seen…. The aim of this society is to rule the world, to appropriate the authority of sovereigns, to usurp their place…. Every species of error which afflicts the earth, every half-baked idea, every invention serves to fit the doctrines of the Illuminati….

I see that all the great fundamentals which society has made good use [of] to retain the allegiance of men — such as religion and law — will be without power to destroy an organization which has made itself a cult, and put itself above all human legislation. Finally, I see the release of calamities whose end will be lost in the night of ages, like those subterranean fires whose insatiable activity devours the entrails of the globe and escapes into the air with a violent and devastating explosion.

Jean Baptiste Carrier, the cold-blooded Jacobin executioner, “entertained a peculiar hatred for children — ‘they are whelps,’ he said, ‘they must be destroyed,’” wrote Nesta Webster in The French Revolution. “The details of these massacres far surpass in horror anything that took place in Paris during the height of the Terror; there young children at least were spared, but at Nantes they perished miserably by the hundreds. The annals of savagery can show nothing more revolting — poor little peasant boys and girls thrust beneath the blade of the guillotine, mutilated because they were too small to fit the fatal plank; 500 driven at once into a field outside the city and shot down, clubbed and sabred by the assassins round whose knees they clung, weeping and crying out for mercy.”

The guillotine was simply too slow to suit the bloodlust of Robespierre, St. Just, Marat, Babeuf, and the others. So the fusillades were begun. Men, women, children, priests, and nuns were herded together and mown down with cannon and muskets, or simply blown up with large charges of powder. Still the executions were too slow. The problem was solved by that mad genius Carrier, who invented the noyades, or mass drownings, which he laughingly called “bathing parties.”

According to Nesta Webster’s World Revolution, the contemporary revolutionary Louis Prudhomme put the total number of victims drowned, guillotined, or shot throughout France at 300,000; of that number only about 3,000 could be considered nobles. And this was simply the warm-up for the really big plans of the revolutionists — what they called the “depopulation.” They believed that France was overpopulated. But they couldn’t agree on whether they should exterminate one-third, one-half, or two-thirds of the population. France at that time was a nation of some 26 million souls; thus, the Jacobin leaders, the great “friends of the people,” were contemplating the slaughter of somewhere between eight and eighteen million of their fellow countrymen! To the guillotine, fusillades, and noyades, they would add forced famines and wars of “liberation” — and undoubtedly many additional manic inventions.

Carrier remarked: “Let us make a cemetery of France rather than not regenerate her after our manner.” It was clear that when Rabaud de Saint-Etienne said, “Everything, yes, everything must be destroyed, since everything must be remade,” he was including the people in his plans of destruction.

Other observers have been led to the same conclusion. Stanley Loomis, the great chronicler of the Terror, wrote: “It is impossible to read of this period without the impression that one is here confronted with forces more powerful than those confronted by men.” Pro-revolutionary historian R. R. Palmer, who gives no hint of being a believer, likewise observed: “Even reasonable men now succumbed to the contagion. A spirit was abroad which contemporary conservatives truly described as satanic.”

Militant Atheism

Christianity was outlawed, the churches nationalized, the clergy slaughtered or forced to swear allegiance to the new cult of “Reason.” Notes Nesta Webster in The French Revolution:

At Notre Dame, stripped of its crucifixes and images of the saints, the Feast of Reason took place on the 10th of November. A temple was raised in the aisle on the summit of a mountain, from which shone forth the “light of truth,” and amidst the strains of the “Marsellaise” and “Ça ira” the Goddess of Reason, personified by [opera singer] Mlle. Maillard, dressed in a blue mantle and [a] red cap of liberty, was borne in procession and solemnly enthroned to the cries of “Vive la Republique! Vive la Montagne!”

Viciously militant atheists like Baron Anacharsis Clootz, Jacques Rene Hebert and the Marquis de Sade vied for the honor of top blasphemer. Clootz bestowed upon himself the title, “the personal enemy of Jesus Christ.” “The People,” he declared, “is the Sovereign and the God of the World; France is the centre of the People-God.”

Illuminati conspirators had to expunge even the calendar, since it was dated from the birth of Jesus Christ. They devised their own pagan, “New Age” calendar, with the year 1 beginning in 1792. The year was to consist of 12 30-day months, each divided into three decades (weeks of 10 days). The months’ names were based on nature: Brumaire (the mist), Frimaire (frost), Prairial (meadow), Thermidor (heat), etc. They inaugurated new pagan festivals in an attempt to wean the stubborn French populace from its Christian moorings. But it was their attacks on the Church and the Faith that finally doomed the revolutionists.

Diabolical Jacobins did not evaporate when the Little Corsican “plucked the Crown of France from the mud with his sword.” They went underground and fomented revolution worldwide. The French Revolution was the archetype from which all future revolutionary conspirators would draw inspiration and practical knowledge. The Russian anarchist Prince Kropotkin said in 1908: “[T]he Great Revolution … was the source and origin of all the present communist, anarchist, and socialist conceptions.”

Nicolai Lenin himself said: “We, the Bolsheviks, are the Jacobins of the Twentieth Century, that is, the Jacobins of the proletarian revolution….” When he was searching for a ruthless henchman to head the Cheka (the forerunner of the KGB), he asked, “Where are we going to find our Fouquier-Tinville [the infamous Jacobin executioner]?” The leaders of the bestial Khmer Rouge Communists who devastated Cambodia attended universities in Paris, where they were steeped in the glorious carnage of the French Revolution. Their programs of depopulation and auto-genocide were taken directly from Robespierre and his fellow conspirators — and made even deadlier by superior 20th Century military technology.

When Mikhail Gorbachev addressed the United Nations in New York on December 7, 1988, he paid tribute to his Illuminist-Jacobin forebears. “Two Great Revolutions — the French Revolution of 1789 and the Russian Revolution of 1917 — exercised a powerful impact on the very nature of the historical process, having radically changed the course of world development,” proclaimed Gorbachev. “The two revolutions, each in its own way, gave a huge impulse to human progress [and] contributed to forming the pattern of mentality that continues to prevail in the minds of people.”

“The end of the Reign of Terror did not bring an end to the French Revolution,” Professor Warren Carroll reminds us in his book, The Guillotine and the Cross. “The forces it unleashed, though to some extent harnessed and stripped of their most obviously evil … elements, continued to batter Europe and threaten the whole world.” Nor has there been any abatement: “It is with us still, now in our time when a third of the world lives under the tyranny of its direct descendant, the Communist Revolution, and the rest of the world is touched and twisted by its legacy in thought and action — often misunderstood, but no less and perhaps more potent for that.”