In an April 12 post, the Independent Institute writes:

James Madison and his colleagues “would have been astonished” at the Supreme Court’s holding that the Amendment “grants individuals a right to have guns….” Instead of “the Minuteman at Lexington, with a musket in his hands … the more accurate image [of the Second Amendment] is that of the musket in the hands of the militiaman on slave patrol in the South.”

The institute is referring to the ridiculous claims made by Carl Bogus in a newly published book about the Second Amendment: Madison’s Militia: The Hidden History of the Second Amendment.

Bogus describes his book as a “hidden history” because, he asserts, “there is no direct evidence about what the Founders intended.”

I would counter that claim with an assertion of my own: the historical record is very clear about the Founders’ intention in drafting and ratifying the Second Amendment. But Bogus doesn’t like what it shows.

Evidence of this is found in passages from Bogus’ book in which he claims that during the ratification debates in Virginia, Patrick Henry declared that without the state militias, the federal government would “subvert the slave system indirectly.”

Now, the record of the Virginia Ratification Convention are available here, and anyone can read every word spoken by Patrick Henry, James Madison, George Mason, and many other Founding Era luminaries, and you won’t find Henry making such a sick assertion in that record.

Bogus goes on to admit that while Patrick Henry didn’t say it, he meant it. Bogus, who must have some supernatural access to Patrick Henry’s brain, writes that Henry advocated for that position “without spelling it out in so many words.” He explains away the fact that the record reveals that Patrick Henry never said these words by saying that “public discussion of it was often frowned upon.”

Bogus obviously has studied the history of the Constitution and the ratification thereof from different sources than the ones I used.

Bogus’ final claim is that James Madison supported the Second Amendment because he realized that there was no way to keep the militia free from federal control unless the Second Amendment was passed.

Again, No.

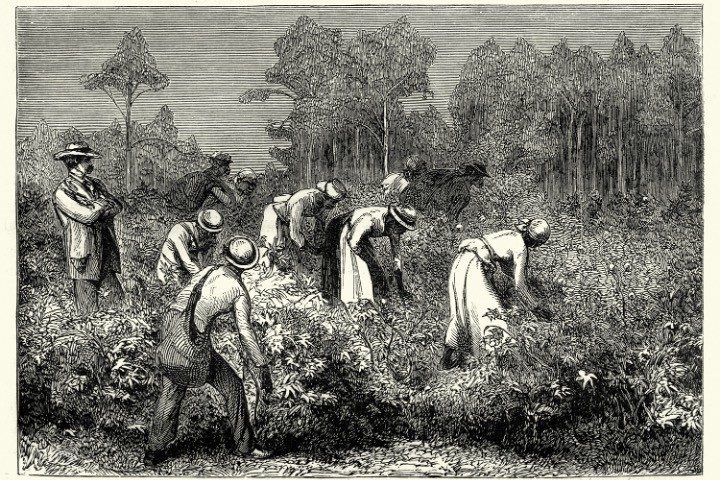

If you were to read Bogus’ book, you’d notice that he spends almost every page attacking the concept of the citizen-militia, basing that attack on his erroneous assertion that the citizen-militia was merely the quasi-military arm of slaveowners.

What Bogus does not mention, however, is the right to keep and bear arms.

I could write 100,000 words on the history of the Second Amendment — including the necessity of the militia and the concomitant individual right to keep and bear arms — but as this is an online article, I’ll keep it brief.

You would notice in that 100,000-word history of the Second Amendment that a couple of facts pop off the page. First, the right of the individual to keep and bear arms was accepted as a natural right, not one “granted” (as Bogus wrote) by government. Second, the right to keep and bear arms is always mentioned in connection with the militia, and the militia is always mentioned in connection with the right of the people to, as the Declaration of Independence reads, “alter or abolish” tyrannical government and to “throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.”

Let’s start with the first fact of the history of the Second Amendment and the principles expressed therein.

You will notice in the language of the Constitution the very distinct and telling use of two very important words: “right” and “power.”

Government is never spoken of as having the “right” to do anything; it is granted the “power” to do certain enumerated things, but not once is it said that the government has a “right” to do any of the things on that list.

The people, on the other hand, have rights. Those rights may be granted to government, but they by nature belong to the people and may be disgorged from government should the government begin abusing the power granted to it by the people.

The people, using their natural right to govern themselves, grant to government powers they — the people — believe are necessary to the protection of their lives, liberty, and property.

Government exists for one reason and one reason only: to secure the rights of the people. Period.

Again, all of this can be found in the black letter of the Declaration of Independence. As an aside, one cannot understand the Constitution without first coming to comprehend the political philosophy set out in that seminal document.

It would be irrational and illogical for a group of people to elect from among themselves another group of people to secure the rights of the whole, and then to assume that those elected for that purpose could somehow be possessed of power to deprive the people of their ability — the right could never be taken, it could only be infringed — to change the guardians or the government if they become tyrannical.

And the Founding Fathers did no such thing.

For the Founding Fathers knew that throughout the history of mankind, there were many times when a man or a group of men tasked with protecting the lives, liberty, and property of the people began destroying those very rights. The people, after exhausting peaceful means of removing tyrants, often had to turn to the use of weapons to defeat those tyrants and displace them from their positions of power.

This fact is known not only to the people, but to the tyrants, as well. Thus, if there were a book called Tyranny for Dummies, one of the first chapters would be “Disarm the People.” As Blackstone wrote: “Free men have arms, slaves do not.” If a tyrant wants to force his will on a people in defiance of their rights, he must first make sure they don’t have the ability to put up an armed resistance to him and his army.

That’s why you will find in the records of the rights of the people of England and of the United States that the right of the individual to keep and bear arms is always connected with the right to depose despots at the point of a gun, when other means are exhausted.

In fact, the right of the individual to keep and bear arms is so enmeshed in English and American history that it is one of only 13 rights specifically protected in the English Bill of Rights of 1689, rights described in that document as being “true, ancient, and indubitable.”

Next, the people themselves are the source of any power possessed by government, and the people have the right to reclaim the authority they provisionally granted to that government.

Throughout the history of England and America, the notion that there should be a standing army was anathema to the understanding of a free, republican state.

To our ancestors, the right to keep arms was ensured so that, if it became necessary, those arms could be borne in defense of liberty.

There are many places one might read of the history of militias (I wrote a little about it here), so I’ll simply restate here that the militia was defined as the men of a community who were old enough and healthy enough to wield a weapon in defense of his and his neighbors lives, liberty, and property.

The idea that still persists among people who should know better — that the right to keep and bear arms was intended to apply only to the army or the national guard or any other such select group of men — is not supported anywhere in the history of the Second Amendment. In fact, had such a suggestion been made at the time of the debating and ratifying the Second Amendment, there would have been no Second Amendment, for there would have been a furious rejection of such an idea and the states would never have approved such an amendment.

Finally, there is not a single syllable in the multi-volume record of debates on the drafting and ratification of the Constitution that would indicate to any sane person a “hidden” or “encoded” intent by the Founding Fathers to use the Second Amendment to secretly protect slavery.

No. That record is replete with speeches and addresses reaffirming that “true, ancient, and indubitable” right of the individual to keep and bear arms. Furthermore, it is replete with reminders from the history of formerly free societies that sometimes it is necessary for a people to exercise their natural right to protect their lives, liberty, and property by forming citizen-militias to put up armed resistance to tyrants bent on destroying those very rights.