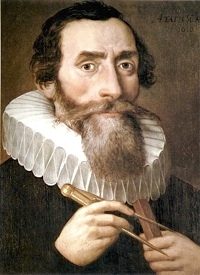

December 27 marks the birthday of the Father of Celestial Mechanics, Johannes Kepler. Born in 1571, he went on to become one of the most important scientists in the field of astronomy as the first person to explain the laws of planetary motion. He also made important advances in the fields of optics, geometry and calculus. Kepler is credited with explaining how the moon influences the tides and with determining the exact year of Christ’s birth.

Johannes was the eldest of six children, three of whom died in infancy. His father abandoned the family when Johannes was only 5 years old. Plagued by ill health in his childhood, he was drawn toward his studies rather than more physically demanding work. In 1594 he became a professor of astronomy and mathematics in Austria, and two years later published his first work entitled Mysterium Cosmographicum, which received critical acclaim. He was named Imperial Mathematician in 1601 by the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II, and in that capacity published his first two laws of planetary motion under the title Astronomia Nova. Ten years after that work, in 1619, the culmination of Kepler’s research appeared in five books entitled De Harmonices Mundi (The Harmonies of the World), which included his third law. The three principles are summed up as follows:

• The planets circle the sun in elliptical orbits with the sun’s center of mass as one of two foci;

• A straight line joining each planet with the sun (i.e., the radius vector) sweeps out equal areas in equal intervals of time;

• The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. This law determines the relationship of the distance of planets from the sun to their orbital periods.

The distinguishing aspect of Kepler’s studies from that of scientists such as Copernicus and Galileo was that he did not confine himself to the examination of our solar system but searched for universal principles governing celestial movement. He was the first to determine the elliptical orbits of heavenly bodies, obliterating the time-honored yet erroneous principle of circular celestial motion.

When Kepler learned of the Copernican theory of heliocentrism, he dedicated his studies to the discovery of these laws. Initially, he attributed Earth’s rotation on its axis to an animating principle of universal attraction; later, Sir Isaac Newton would expand and perfect this hypothesis in his law of gravitation which states that bodies are attracted to each other in direct proportion to their mass and inversely as to the square of the distance between them.

It was this same principle of material attraction that led Kepler to observe the waters of the sea responding to the movement of the moon. Again, Newton capitalized on Kepler’s research to explain the lunar tides.

His theories were not the only legacy Kepler left for future scientists to build upon. In 1611, he invented the modern refracting telescope, which made possible many of the later discoveries born from Kepler’s hypotheses. He is even considered the father of science fiction, having written a novel entitled Somnium about a trip to the moon.

Kepler passed away on November 15, 1630, at the age of 59. He is buried in Regensburg, Germany, though the exact location of his grave is unknown. The cemetery was desecrated in 1633 by a Swedish Army during the Thirty Years War.

Throughout his career, Kepler humbly credited his genius not to himself, but to God. Despite his extensive discoveries, he made the claim that mankind would never be without new phenomena to explore, so great is the diversity, complexity and richness of God’s creation. He wrote: “Great is God our Lord, great is His power and there is no end to His wisdom. Praise Him you heavens, glorify Him, sun and moon and you planets. For out of Him and through Him, and in Him are all things… We know, oh, so little. To Him be the praise, the honor and the glory from eternity.”

Citations

Duhem, P. (1911). History of Physics. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 22, 2010 from New Advent.