The year is 1942. Approximately 400,000 Jews have been forced by Nazi Germany to live under horrid conditions in a 1.3-square-mile area known as the Warsaw Ghetto. Starvation, disease, despair, and death run rampant, but even this is not enough to satisfy Hitler’s bloodlust. The Nazis begin deporting Jews from the ghetto to Treblinka, an extermination camp about 60 miles from Warsaw.

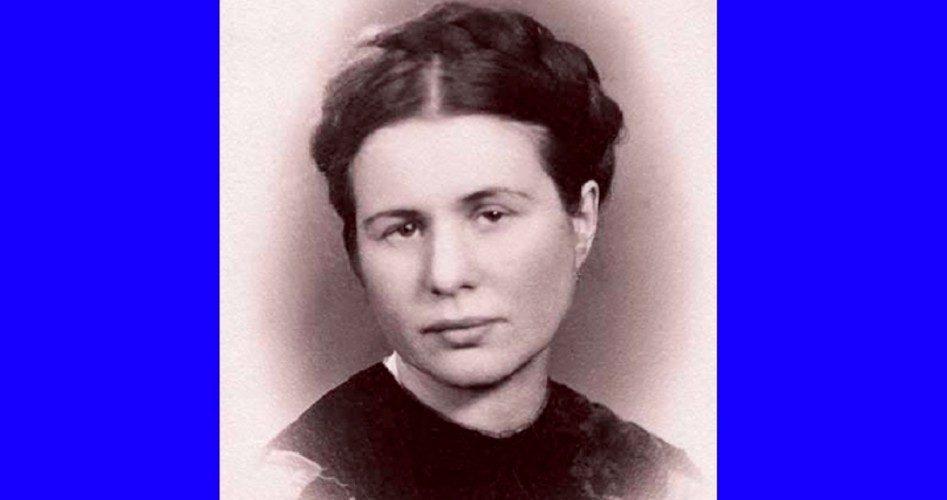

Aware of the certain death awaiting those sent to Treblinka, Polish social worker Irena Sendler (shown) intensifies her efforts to help the Jews in the Ghetto, knowing that the only way to save the children is to get them out. She faces the heart-wrenching task of convincing Jewish parents to part with their children and trust complete strangers to keep them safe.

Like most families, the Wolmans did not want to give up their child.

“Is it better for Elka to suffer and starve behind these walls?” Irena asked. “And what will happen when the soldiers come to send you to the camp at Treblinka?”

“The Nazis say no harm will come to us there,” Mr. Wolman argued.

“That’s a lie,” Irena told him. “The people who go there are killed.”

Mrs. Wolman’s face was wet with tears. “If we give you our daughter, can you promise us she’ll live?”

“No,” Irena said. “But if she stays here she will surely die.”

“How will we get back together when the war is over?” Mr. Wolman asked.

“I’ll keep your child’s real name and new identity on a secret list so you can find her,” Irena promised the worried parents.

Suddenly the door downstairs slammed open, and the sound of soldiers’ boots pounding on the front steps echoed upstairs.

“They’re coming!” Mrs. Wolman cried. “Take her!”

The Wolmans quickly kissed Elka good-bye. The child cried out as Irena took Elka from her mother’s arms and hurried away through the hall and down the back stairway.

This is how author Marcia Vaughan dramatized one of Irena’s rescues in her book Irena’s Jars of Secrets. Irena carried little Elka to safety, and she kept her promise to record the true names and false identities of the children she helped on slips of paper buried in jars under an apple tree in the backyard of her friend and co-worker Janina Grabowska. Sadly, very few of the parents survived to be reunited, yet some 2,500 children lived through the war thanks to Irena and her network of mostly young women who risked everything to get Jewish children out of the ghetto and placed with Polish foster parents or hidden among other Polish children in convents and orphanages.

Conscientious Beginnings

While Irena Sendler is the person most responsible for saving those 2,500 children, it could be said that each one of those survivors owes a debt of gratitude to Irena’s parents for correctly forming her conscience as a child. The website www.irenasendler.com is dedicated to telling Irena’s story based on in-person interviews conducted with Irena before her death on May 12, 2008, and the site credits Irena’s parents for her moral upbringing, saying that she “was raised by her parents to respect and love people regardless of their ethnicity or social status.”

Irena was born on February 15, 1910, in Warsaw, Poland, but grew up in the nearby town of Otwock. It was in Otwock that her father served as the only doctor willing to treat the poor, primarily Jewish townspeople for typhus. He himself contracted the disease in 1917, and as he was dying, he told seven-year-old Irena, “If you see someone drowning you must try to rescue them, even if you cannot swim.” She never forgot this and would later say in an interview recorded by the PBS documentary Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers, “As for me, it was simple. I remember what my father had taught me. When someone is drowning, give him your hand. And I simply tried to extend my hand to the Jewish people.”

Following this line of thought, Irena dedicated her life to helping others and had become a director of social services in Warsaw by the time war broke out in 1939. After the Nazis began forcing Jews into the ghetto in late 1940, she procured a nurse’s uniform and identification papers from the government’s contagious disease department, enabling her to enter and do whatever she could to help. Irena’s Jars of Secrets describes the scene that met Irena’s eyes inside the walls of this hell on Earth:

Entering the ghetto was like entering a nightmare. The people inside were struggling to survive. They did not have enough food, water, medicine, or heating fuel.

Irena’s heart filled with grief. As she walked through the ghetto, hungry children cried out. People lay sick and starving in the streets. Everywhere Irena turned, she saw death and despair.

Irena would later describe her experience within the ghetto in Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers by saying:

The first time I went into the ghetto it made a hellish impression on me. There were children on the street … starving … begging for a piece of bread. I’d go out on my rounds in the morning and see a starving child lying there. I’d come back a few hours later, and he would already be dead … covered with a newspaper.

Moved with compassion, Irena looked for ways to alleviate the suffering of those trapped in this horror. She began to smuggle in food, medicine, and clothing, and to file with the Germans false documents that contained made-up Polish names of those who supposedly qualified for aid — aid that Irena and her team would then distribute to the Jews. She quickly realized that the children were bearing the brunt of the hardship, especially the orphans who were left to fend for themselves on the streets.

Despite her best efforts and the help of those she could recruit to her cause, Irena could only do so much. When the trains bound for Treblinka began to show up at the Umschlagplatz train yard in the ghetto in 1942, Irena knew that she would need even more help to get children out before whole families were forced to take this one-way trip.

Joining the Underground

Fortunately for Irena, the London-based, legitimate Polish government-in-exile had formed the Council for Aid to Jews — code-named “Zegota” — to assist Jews in escaping from the Nazis. Zegota began to work closely with Irena and her helpers to rescue children from the ghetto, starting with the orphans. Irena was made head of the children’s division of Zegota and given the code-name “Jolanta.”

Zegota provided money and forged documents to Irena, enabling her network to do more, although now they were fighting the clock with even greater desperation as trainloads of thousands of Jews were regularly leaving for Treblinka, in addition to the thousands already dying of starvation each month. As Irena’s efforts expanded from focusing on orphans to including children from Jewish families, she faced the agonizing task of convincing parents to relinquish their sons and daughters into her care.

Parents were understandably hesitant to trust strangers with their children, and they were reluctant to believe the worst news about Treblinka being not a place for relocation but extermination. Also, faithful Jewish parents knew that their children would have to masquerade as Christians, taking Christian names and learning Christian prayers, if they were to survive with Polish foster families or at convents or orphanages. The parents justifiably feared that their children would lose their Jewish heritage and beliefs. All too often Irena would plead with the parents to let their child go, but they just could not bear the thought. Irena would return a day or two later intending to try again to persuade the parents only to find their home empty and the family already deported to Treblinka.

Irena recounted the trauma of these situations in Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers:

Those scenes over whether to give a child away were heart-rending. Sometimes, they wouldn’t give me the child. Their first question was, “What guarantee is there that the child will live?” I said, “None, I don’t even know if I will get out of the ghetto alive today.” I still have nightmares about it.

Despite the discouragement of such situations, Irena was able to accomplish much with Zegota’s aid. Many ingenious methods were devised to get children out of the ghetto. A number of infants, small in comparison to the total number of children rescued, were sedated and smuggled out with no fear of them making noise. One of these infants, Elzbieta Ficowska, was only five months old when she was taken from her parents and smuggled out by a kindly building contractor while she was hidden in a wooden box amid a pile of bricks. Elzbieta had with her a silver spoon engraved with her name and birth date; this was to become her only memento of her parents, who did not survive the war. Happily though, Elzbieta did find Irena later in life and thanked her rescuer by helping to care for Irena in her old age.

There were other ways to get older children out of the ghetto. A truly sick child could be legally taken out of the ghetto in an ambulance, while a child who was able to fake being sick could also be removed this way. Other children could simply be hidden under a stretcher in the ambulance when it left the ghetto. A child could hide in a sack, trunk, suitcase, or similar container and be carried out of the ghetto aboard a trolley. Garbage was occasionally hauled out of the ghetto, and children could be hidden amongst the refuse until the vehicle arrived at the dump. Underground passages or sewers could be used to get a child out, and there was a courthouse with an entrance inside the ghetto and an exit on the outside of the wall.

Unfortunately for Irena, this rescuer of so many children was soon to need rescuing herself after the Nazis discovered her role in Zegota. On October 20, 1943, Irena was arrested and taken to the notorious Pawiak Prison. Interrogated and tortured to the point of suffering fractures to her legs and feet that would permanently hinder her ability to walk, Irena nonetheless steadfastly refused to divulge the names of Zegota members or the children she had saved. She was sentenced to death and was on her way to execution when the miracles she had arranged for so many innocent children came back to her in the nick of time.

Unbeknownst to Irena, Zegota had bribed a guard to release her while keeping her name on the list of executed prisoners. Irena was set free and whisked away into hiding, assuming the false identity of Klara Dambrowski for the remainder of the war and ironically finding herself in the same situation she had arranged for so many others. Irena herself saw the posters declaring that she had been killed, though her escape was eventually found out. Even from hiding, Irena/Klara continued to help smuggle children out of danger.

After the War

World War II came to an end, but Irena’s sacrifices for saving so many lives did not. She managed to return and dig up the lists hidden in the jars beneath the apple tree, and made every effort to locate surviving parents and reunite them with their children. Irena’s heart was grieved when she found out that nearly all of the parents she tried to find had perished, and she eventually turned the lists over to Zegota officials.

Irena did have the joy of marrying Stefan Zgrzebski after the war (Sendler is derived from the surname of her first husband, Sendlerowa), and had two children — a boy and a girl — by that marriage. But the communist government that took over from the Nazis harassed Irena for her involvement with the legitimate Polish underground rather than the communist underground. Her times of imprisonment and interrogation by the communist authorities caused Irena so much stress that she suffered a miscarriage.

There were other, brighter moments though, such as when Yad Vashem — the Jewish center for documentation, research, education, and commemoration of the Holocaust — declared Irena one of the Righteous Among the Nations on October 19, 1965. The tree planted in her honor still stands at the entrance to the Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations. Even this honor did not lead to Irena gaining much attention for her wartime efforts. She lived in relative obscurity until an American high-school teacher unknowingly started three of his students on a quest to bring Irena the recognition she so richly deserved.

Unburying Irena’s Secrets

In the fall of 1999, Norm Conard, a teacher at a rural Kansas high school, encouraged three students — ninth-graders Megan Stewart and Elizabeth Cambers, and eleventh-grader Sabrina Coons — to work on a National History Day project that could span the entire year. As a suggestion, he showed the girls a 1994 U.S. News & World Report article entitled “The Other Schindlers,” a piece obviously inspired by the popularity of Steven Spielberg’s cinematic epic Schindler’s List.

“The Other Schindlers” stated that “Sendler successfully smuggled almost 2,500 Jewish children to safety and gave them temporary new identities.” Conard was initially skeptical that Irena could have helped so many more people than the 1,200 Schindler saved, especially considering that he had never heard of her before. Fortunately, Megan, Elizabeth, and Sabrina demonstrated the same initiative that Irena had, and they accepted the challenge to research this Polish social worker whose list of saved names so far surpassed Schindler’s.

Much to the girls’ surprise, they found out that Irena Sendler was still alive and living in Warsaw. Irena’s husband and son had since died, and her health was declining, but she returned their correspondence, beginning a friendship with the girls that would grow and deepen until Irena’s death. The students eventually wrote a play they called Life in a Jar to dramatize and publicize Irena’s rescue work. Life in a Jar has since been performed more than 300 times, with proceeds going to support Irena and other rescuers. Irena was so touched by what the girls were doing that she wrote to them:

My emotion is being shadowed by the fact that my co-workers have all passed on, and these honors fall to me. I can’t find words to thank you, for my own country and the world to know of the bravery of rescuers. Before the day you had written Life in a Jar, the world did not know our story; your performance and work is continuing the effort I started over fifty years ago. You are my dearly beloved ones.

In January of 2001, a Jewish educator and businessman saw a performance of Life in a Jar and offered to raise the funds to send the students to Poland to meet Irena in person. This was a dream come true for the girls, and they gladly accepted. In May of that same year, the students and their teacher traveled to Warsaw and finally met Irena and others who were part of her story, including Elzbieta Ficowska. There were several subsequent trips back to Poland to be with Irena before she passed away, and the repeated performances of Life in a Jar gradually brought Irena’s story more and more attention.

Irena was given the Jan Karski Award for Valor and Courage in 2003. This honor caused her to be noticed by another person of Polish descent who was quite a bit more well known, the late Pope John Paul II, who sent Irena the following letter:

Honorable and dear Madam, I have learned you were awarded the Jan Karski prize for Valor and Courage. Please accept my hearty congratulations and respect for your extraordinarily brave activities in the years of occupation, when — disregarding your own security — you were saving many children from extermination, and rendering humanitarian assistance to human beings who needed spiritual and material aid. Having been yourself afflicted with physical tortures and spiritual sufferings you did not break down, but still unsparingly served others, co-creating homes for children and adults. For those deeds of goodness for others, let the Lord God in his goodness reward you with special graces and blessing. Remaining with respect and gratitude I give the Apostolic Benediction to you.

In 2007, ABC News interviewed Irena in Warsaw. At the time, many of the surviving children whom she had saved worked to nominate Irena for the Nobel Peace Prize. Frustratingly, Al Gore won the prize that year, but this did not bother Irena in the least. Her characteristic humility showed forth in her interview with ABC:

I have to share all credit with the 30-odd people who worked with me. Alone, I couldn’t have done it. It was 30 brave people. None of them are alive today. One of my helpers was executed. I’m the only survivor.

Sadly, Irena was not to survive much longer, passing away in 2008. The following year Hallmark Hall of Fame released a movie that told her story: The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler. Anna Paquin starred as Irena. Then in 2011, PBS released Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers, which included interviews with Irena recorded years earlier. Books such as Irena’s Jars of Secrets have been published over the years. Irena’s story has now been told in print and video as well as on stage and many websites. Thanks to a few high-school students and their teacher, Irena Sendler will never be forgotten.

ABC News also interviewed Elzbieta Ficowska in 2007, and the way she remembers Irena shows great insight.

Irena represents the often forgotten truth that no one should be indifferent. Irena became a symbol — a symbol of something very good, a symbol of undeniable authority. In today’s world of eroding values in which role models crumble one after another, it’s particularly the young who need people like Mrs. Sendler.

Young and old alike need Irena Sendler’s example of conscientious courage cloaked in self-effacing modesty. As Irena told ABC News, “After the Second World War, it seemed that humanity understood something and that nothing similar would happen again.” She then added, “Humanity has understood nothing. Religious, tribal, national wars continue. The world continues to be in a sea of blood.”

But Irena smiled and concluded with words that she herself had lived up to: “The world can be better if there’s love, tolerance, and humility.”