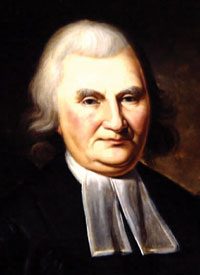

On November 15, 1794, a 72-year-old Presbyterian preacher lay dying on his farm near Princeton, New Jersey. In some ways he may have welcomed death. His wife had died five years earlier, and for over two years he had been blind, so his associates had to lead him into the pulpit, where he still preached with his usual earnestness and perhaps with more than his usual solemnity and animation. Even though his bodily infirmities increased, his mind remained active to the end, and he continued to exercise his duties as pastor and college president until the end.

His name was John Witherspoon, and he was probably the most famous and respected clergyman in America at that time. For 26 years he had served as president and professor at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). In those 26 years, 478 young men graduated from the college, an average of 18 in each class, so Witherspoon had considerable interaction on and influence with each student. Of those young men, 114 became pastors; 13 were state governors; three were U.S. Supreme Court justices; 20 were U.S. senators; 33 were U.S. congressmen; one, Aaron Burr, Jr., became vice-president; and another, James Madison, became president. If Madison can be called the Father of the Constitution, then Witherspoon deserves the title Grandfather of the Constitution.

A Life of Accomplishment

During those final hours, the old reverend probably reflected upon his life, wondering whether his efforts had been productive and his sacrifices worthwhile. He may have thought about his early years in Scotland, where he was born in 1722. John Witherspoon’s father was a Presbyterian clergyman, and his mother traced her genealogy back to the founder of Presbyterianism, John Knox. Mrs. Witherspoon taught her children at home, and John could read from the Bible at age four. He then attended grammar school, and at age 14 he enrolled in the University of Edinburgh, where he earned a Master of Arts degree in three years and then completed his studies for the ministry by age 20.

Witherspoon’s first call was to the Presbyterian church at Beith, Scotland, where he served eight years. Shortly before this time, the Scottish Jacobites had fought for independence from England, and the Scottish spirit of independence may have influenced Witherspoon throughout his life. At this time the Scottish church was split between the popular party and the moderates. The popular, or evangelical, party stressed Bible-centered sermons and local control of the church. Witherspoon soon emerged as a leader of the evangelical party, and a satirical pamphlet attributed to him called Ecclesiastical Characteristics ridiculed the moderates.

In 1757, either in spite of or because of this pamphlet, Witherspoon was called to the pastorate of Laigh Kirk (Church) in Paisley, considered the intellectual center of Scotland, where "every weaver is a politician." At Laigh Kirk, Witherspoon preached a sermon entitled "The Absolute Necessity of Salvation Through Christ," in which he declared that salvation by grace and the gospel of Jesus Christ must not be compromised. Moderate Presbyterians charged that Witherspoon’s sermon lacked Christian charity; Witherspoon responded with a sermon entitled "Inquiry into the Scripture Meaning of Charity," in which he declared that true charity includes "an ardent and unfeigned love to others and a desire for their welfare, temporal and eternal." Witherspoon insisted that charity requires "the deepest concern for their dangerous state," and that one who does not care about the salvation of people’s souls does not practice true charity toward them.

At this time the American colonies were in the throes of the Great Awakening, a religious revival in which hundreds of thousands either became Christians or rededicated their lives to Christ. The College of New Jersey, founded by Presbyterians and led by President Jonathan Edwards, was at the center of the Awakening. Word of Witherspoon’s scholarship and evangelical zeal reached the colonies, and when the time came to call a new president for the College of New Jersey, Witherspoon was their choice.

Witherspoon served as president of the College of New Jersey from 1768 to 1794. Besides being president, Witherspoon also served as Professor of Divinity, and according to an announcement that advertised graduate courses,

The President has also engaged to give Lectures twice in the Week, on the following Subjects (1) On Chronology and History, civil as well as sacred; a Branch of Study, of itself extremely useful and delightful, and at present in the highest Reputation in every Part of Europe, (2) Critical Lectures on the Scripture, with the Addition of Discourses on Criticism in general; the several Species of Writing, and the fine Arts, (3) Lectures on Composition, and the Eloquence of every Student by Conversation according to the main Object, which he shall chuse for his own Studies; and will give Lists and Characters of the principal Writers on any Branch, that Students may accomplish themselves, at the least Expence of Time and Labour.

Witherspoon also was keenly interested in law and politics, having studied the works of Montesquieu and others. The spirit of independence was rising in America, and like most Presbyterians, Witherspoon favored independence, although he also cautioned against excesses. As a Calvinist who believed in the depravity of human nature, Witherspoon tempered his love for liberty with his recognition of the need for order, and this balance kept the American War for Independence from becoming a chaotic bloodbath like the French Revolution.

On May 17, 1776, Rev. Witherspoon preached a sermon entitled "The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Men." Using Psalm 76 as his text, he qualified his opposition to England by saying that "many of their actions have probably been worse than their intentions," but English cruelty and tyranny shall "finally promote the glory of God" by forcing the colonists to declare their independence. He called for attention to religion, declaring that "he is the best friend of American liberty who is most sincere and active in promoting true and undefiled religion and who sets himself with the greatest firmness to bear down profanity and immorality of every kind." He told his listeners that duty to God and duty to country called upon them to be uncorrupted patriots, useful citizens, and invincible soldiers, and he concluded, "God grant that in America true religion and civil liberty may be inseparable and that the unjust attempts to destroy the one may in the issue tend to the support and establishment of both."

Witherspoon later published this sermon with an appendix entitled "Address to the Natives of Scotland residing in America," in which he urged American Scotsmen to assert their "ancient rights" and support American independence. The sermon and appendix were distributed throughout the colonies and were also reprinted twice in Glasgow.

Also in 1776, Witherspoon was elected to the Continental Congress, where he served wearing full clerical garb from 1776 to 1782. He served on more than 120 committees, including the Board of War, the Committee on Secret Correspondence, and the Committee on Clothing for the Army, and helped his fellow congressmen draft the Articles of Confederation. He zealously supported independence, but his Christian charity also led him to call for humane treatment of British prisoners, the checking of cruelty in warfare, the improvement of military hospitals, and better morals and discipline for the army. He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and he lost two sons in the war.

Also in 1776, Witherspoon was elected to the Continental Congress, where he served wearing full clerical garb from 1776 to 1782. He served on more than 120 committees, including the Board of War, the Committee on Secret Correspondence, and the Committee on Clothing for the Army, and helped his fellow congressmen draft the Articles of Confederation. He zealously supported independence, but his Christian charity also led him to call for humane treatment of British prisoners, the checking of cruelty in warfare, the improvement of military hospitals, and better morals and discipline for the army. He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and he lost two sons in the war.

He also preached regularly to his fellow congressmen and others. On February 17, 1777, John Adams wrote in his diary: "Yesterday, heard Dr. Witherspoon upon redeeming Time. An excellent Sermon. I find that I understand the Dr. better, since I have heard him so much in conversation, and in the Senate." And on another occasion, while traveling, Adams attended church at the College of New Jersey and wrote: "Heard Dr. Witherspoon all Day. A clear, sensible, Preacher."

In 1782, with the war nearly over, Witherspoon retired as a congressman and continued his duties as president of the College of New Jersey. But he remained interested in politics and served several terms in the New Jersey state assembly.

He did not attend the constitutional convention, but he did serve as a delegate to the New Jersey ratifying convention and argued zealously for ratification of the Constitution.

But age was taking its toll upon John Witherspoon. In October 1789, his wife Elizabeth died. He threw himself into his work and again entered the legislature, heading a committee to abolish the slave trade in New Jersey. About two years later he married Ann Marshall Dill, a 24-year-old widow. For the last two years of his life, he was blind and had to be led into the pulpit. When he died in 1794, his secretary wrote that his "descent into the grave was gradual and comparatively easy, free from any severe pain, and contemplated by himself with the calmness of a philosopher and the cheering hope of a christian."

As he lay dying, John Witherspoon could contemplate a life of accomplishment: pastor, church leader, college president, assemblyman, congressman, signer of the Declaration of Independence, framer of the Articles of Confederation, supporter of the Constitution. As possibly the best-known clergyman in America at the time, he did much to set the moral and spiritual tone for the new nation, emphasizing that religious liberty does not mean America should be religion-free, and that piety and morality are essential to the stability and strength of the nation.

Witherspoon’s influence on the founding generation would be hard to overstate. James Madison and other great men of that generation were his students, and the lessons they learned from their well-respected professor helped to shape their thinking for a lifetime, both intellectually and morally. In a very real sense, John Witherspoon was the framer of the framers.

Faith and Ideas

The spiritual and ideological foundation that Rev. Witherspoon built for America could be summarized with the following points:

1. A firm faith in God and His daily providence on behalf of men. Some have suggested that the Founding Fathers used the term "Providence" as an impersonal term for a deistic god who is not involved in human affairs, but in fact its meaning is the opposite. Samuel Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary of the English Language defined providence as "1. Foresight; timely care…; 2. The care of God over created beings; divine superintendence." Noah Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language defined providence as "3. In theology, the care and superintendence which God exercises over his creatures. He that acknowledges a creation and denies a providence, involves himself in a palpable contradiction; for the same power which caused a thing to exist is necessary to continue its existence." Witherspoon firmly believed that, in Ben Franklin’s words, "God governs in the affairs of men." He declared, "Shun, as a contagious pestilence, … those especially whom you perceive to be infected with the principles of infidelity or enemies to the power of religion. Whoever is an avowed enemy of God, I scruple not to call him an enemy to his country."

2. A recognition of the fact of human sin. In his "Dominion of Providence" sermon, Witherspoon declared that "the corruption of our nature … is the foundation-stone of the doctrine of redemption. Nothing can be absolutely necessary to true religion, than a clear conviction of the sinfulness of our nature and state." The evil of sin "appears from every page of the sacred oracles," and furthermore, "the history of the world is little else than the history of human guilt." But although Witherspoon accepted the Calvinist view of total depravity, he also believed in common grace, because the unregenerate "have not totally extinguished the light of natural conscience":

"It pleased God to write his law upon the heart of man at first. And the great lines of duty, however obscured by their original apostasy, are still so visible as to afford an opportunity of judging what conduct and practice is or is not agreeable to its dictates."

Even after the Fall of Adam and Eve, man still retains enough of the law written upon men’s hearts (Romans 2:14-15) that he remains a responsible moral agent and is able to function in civil government.

3. The absolute necessity of salvation through Christ. He declared in his Lectures on Divinity that "Religion is the grand concern of us all…. The salvation of our souls is the one thing needful." He called on his audience to "Fly also for forgiveness to the atoning blood of the great Redeemer."

4. A commitment to personal, political, and religious liberty. Government, Witherspoon believed, has no authority over the conscience and soul of man. The greatest service government could render to Christianity, he said, was "to defend and secure rights of conscience in the most equal and impartial manner." Religious liberty and civil liberty go hand in hand, he insisted, because "there is not a single instance in history, in which civil liberty was lost, and religious liberty preserved entire." A cornerstone of this liberty is the right to own and use property, because "if therefore we yield up our temporal property, we at the same time deliver the conscience into bondage."

5. A belief that morality and virtue are essential to the preservation of a free nation. "To promote true religion is the best and most effectual way of making a virtuous and regular people. Love to God and love to man is the substance of religion; when these prevail, civil laws will have little to do…. The magistrate (or ruling part of any society) ought to encourage piety … [and] make it an object of public esteem. Those who are vested with civil authority ought … to promote religion and good morals among all their government." Likewise, he said, "The people in general ought to have regard to the moral character of those whom they invest with authority either in the legislative, executive, or judicial branches."

6. American independence. Just as he believed that local churches have the authority to control their own affairs, so also the American colonies had a right to independence from England. His disdain for English control probably related to his days in Scotland, when Scottish Presbyterians and Catholics fought side by side for independence. In England the American War for Independence was often called the "Presbyterian rebellion," and English Prime Minister Horace Walpole probably had Rev. Witherspoon in mind when he lamented, "Cousin America has run off with a Presbyterian parson."

7. Good works and morality are essential, but they are the results of salvation by grace through faith, not the means of salvation. Such was Witherspoon’s Calvinist belief. Nevertheless, he said, "civil liberty cannot be long preserved without virtue," and a republic "must either preserve its virtue or lose its liberty."

8. The authority of the Bible. "The character of a Christian," he said, "must be taken from Holy Scriptures … the unerring standard." And he devoted his life to instilling biblical principles in all who would listen.

But Witherspoon himself probably reflected that his greatest contribution to America was the 478 young men whom he had influenced at the college. May we too remember that the greatest and most enduring contribution we make to our country may be through mentoring those who come after us.

And although Witherspoon was not physically present at the Constitutional Convention, his influence was certainly felt. Nine of the convention delegates (William Paterson of New Jersey, Jonathan Dayton of New Jersey, David Brearley of New Jersey, William Churchill Houston of New Jersey, Gunning Bedford, Jr. of Delaware, Luther Martin of Maryland, James Madison of Virginia, William Richardson Davie of North Carolina, and Alexander Martin of North Carolina), almost one-sixth of the total delegates, were graduates of the College of New Jersey, and of these at least five were students of Witherspoon.

One of these, James Madison, is often called the "Father of the Constitution." Madison studied for the ministry at the college, and he stayed a semester after graduation to study Hebrew. Madison could read the Old Testament Law in the original language. Under Witherspoon’s teaching, Madison learned the Calvinist view of law and government, that because of the depravity of human nature, government power needs to be carefully limited and separated among branches and levels. All of this Madison could have learned by reading Blackstone, Montesquieu, and other sources; but the concept of checks and balances seems to be the contribution of Dr. Witherspoon, who had stressed that if the three branches of government were entirely independent of one another, each would usurp more power to itself, and therefore, human nature being what is, checks and balances among the various branches and levels of government were necessary to prevent any one level, any one branch, or any one individual in government from becoming too powerful. For that reason he feared unfettered majority rule: "Pure democracy cannot subsist long nor be carried far into the departments of state — it is very subject to caprice and the madness of popular rage." Madison’s oft-quoted words from The Federalist, No. 51, reflect the teaching of the "Old Doctor":

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government wold be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed, and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

And so, in those last hours of his life, Dr. Witherspoon could reflect with satisfaction upon the America he and his disciples helped to create, and he could look with optimism to America’s future. As he told his good friend Rev. Ashbel Green, "Don’t be surprised if you see a turnpike all the way to the Pacific Ocean in your lifetime."

John Ramsay Witherspoon, the Old Doctor’s secretary and third cousin, described him as having "the simplicity of a child, the humility of a patriarch and the dignity of a prince." Dr. Roger Schultz of Liberty University said it well: "[John] Adams called him a true son of liberty. So he was. But first, he was a son of the Cross."