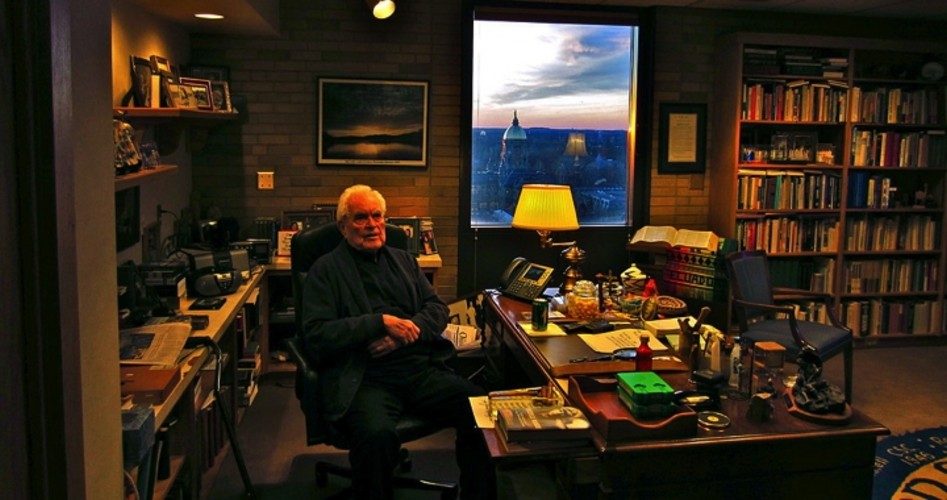

Former Notre Dame President Father Theodore Hesburgh (shown at right) passed away on February 26 at age 97. One day earlier, veteran Notre Dame Law School Professor Charles Rice (shown below) died at 83. The two men spent most of their lives at the famous university in Indiana but the roles they played were remarkably different. While both of these Notre Dame stalwarts were born and raised in the state of New York, those roots were perhaps their only similarity other than Notre Dame itself. One was a staunch conservative politically and religiously; the other could easily be classified as his polar opposite.

Charles Rice was born in 1931 in New York City, graduated from Holy Cross College in Massachusetts, and served on active duty for several years as an officer in the United States Marine Corps. He later retired with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Marine Reserve. After earning a law degree at Boston College, he practiced law while teaching at both Fordham University Law School and New York University Law School. He played an important role in the creation of New York’s Conservative Party. In 1969, he joined the faculty at Notre Dame Law School where he taught until retiring in 2000. Even then, he continued to teach an elective course entitled “Morality and the Law” during his retirement years. He was a great advocate of the philosophical thinking of Thomas Aquinas.

Well loved by his students, Rice authored 14 books, several of which attacked the practice of abortion. His works also upheld Catholic opposition to euthanasia, contraception, and in vitro fertilization. He always stressed natural law, which he insisted was ingrained in every sentient person. His memberships in The Cardinal Newman Society and a place on the board of Ohio’s Franciscan University and the Eternal Word Television Network provided guidance to those institutions. He also served as chairman of the Kentucky-based Center for Law and Justice International and as a director of the Michigan-based Thomas More Law Center. He contributed numerous articles to The New American magazine, and was a featured speaker at several John Birch Society events. For several years, Professor Rice spoke to campers at The John Birch Society’s summer camp in Indiana. He and his wife Mary raised 10 children and had 41 grandchildren when he died.

Well loved by his students, Rice authored 14 books, several of which attacked the practice of abortion. His works also upheld Catholic opposition to euthanasia, contraception, and in vitro fertilization. He always stressed natural law, which he insisted was ingrained in every sentient person. His memberships in The Cardinal Newman Society and a place on the board of Ohio’s Franciscan University and the Eternal Word Television Network provided guidance to those institutions. He also served as chairman of the Kentucky-based Center for Law and Justice International and as a director of the Michigan-based Thomas More Law Center. He contributed numerous articles to The New American magazine, and was a featured speaker at several John Birch Society events. For several years, Professor Rice spoke to campers at The John Birch Society’s summer camp in Indiana. He and his wife Mary raised 10 children and had 41 grandchildren when he died.

Disappointed and even angered by what was occurring at Notre Dame, Rice expressed his discontent with the university’s drift away from its roots in his 2009 book What Happened to Notre Dame? One incident stressed in this book discussed the protest by many in the Notre Dame community over the proposed appearance on campus of President Barack Obama to deliver a commencement address in 2009. More than 360,000 persons signed a petition asking Notre Dame President Father John Jenkins to rescind the invitation. High on the list of complaints about Obama was the president’s long advocacy of abortion on demand. Two Catholic Cardinals also protested the invitation along with 83 bishops. A sizeable number of disappointed Notre Dame alumni cancelled pledges totaling $14 million to the school. However, the invitation was not withdrawn and President Obama did deliver the speech in which he never backed down from his support of abortion while lecturing the audience about the need for all to bury differences and “live together as one human family.”

William Dempsey, chairman of an alumni group known as Sycamore Trust, commented that Rice was “a treasured mentor to countless students, a gifted natural law proponent, a pioneer in the pro-life movement at the university, and a courageous and relentless critic of the forces of secularization at work at Notre Dame and in Catholic higher education in general.”

Father Wilson Miscamble, a member of the Notre Dame faculty, said of his deceased close friend, “Professor Charles Rice epitomized all that is best about Notre Dame. His love for God, his family, his country, and the university was deep and lasting.” Father Miscamble had set himself at odds with the administration when he delivered a strong message at a rally held on campus to protest the appearance of President Obama.

Theodore Hesburgh was born in 1917 and raised in Syracuse, not in New York’s largest city as was Charles Rice. He claimed to have aspired to be a priest from the age of six. Some of his seminary training occurred at Notre Dame, much of it in Rome. Ordained in 1943 and assigned to Notre Dame as a member of the Holy Cross Fathers who built the institution, he won appointments as the leader of its religion department in 1948, vice president in 1949, and president in 1952. Many remarked that at 35, he was unusually young to be given such a prestigious post.

In 1950, he participated in a Ford Foundation project, his first known contact with America’s leftist establishment. In 1961, his acceptance of appointment to the board of the Rockefeller Foundation (he was later named its chairman) raised more eyebrows because of its funding of pro-abortion and population-control organizations. He later arranged a private meeting with Pope Paul VI for John D. Rockefeller III to request that the Catholic Church relax its strict stand against contraception. In 1968, after the Pope condemned that practice in his Humanae Vitae encyclical, Hesburgh publicly supported an outspoken priest member of the Notre Dame faculty who defiantly opposed the Pope’s condemnation. In 1969, the Notre Dame leader added his name to an ad placed in the New York Times extolling the efforts of the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) to force instruction about sex to youngsters in school, even those in primary grades.

As early as 1967 at a gathering of American Catholic Colleges leaders held at a Notre Dame retreat center in Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin, Hesburgh steered the group into eliminating unwanted church influence at their schools. The official statement emanating from that gathering declared that “the catholic university must have true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical.” That attitude, a virtual secession from all Church authority, immediately spread throughout Catholic higher education and gave impetus to most Catholic institutions tolerating uncatholic attitudes and practices, replacing clergy on their boards with lay persons, and downgrading instruction in the Catholic Faith.

The long-serving president of Notre Dame would later call for making the world “somewhat divine” in a work where he promoted a form of New Age pantheism he called “Christian Humanism.” In his 1974 address to the Catholic Press Convention meeting in Colorado, he referred to anti-abortion partisans as “mindless and crude zealots.” He would later allow Notre Dame to host the annual convention of the Planned Parenthood Federation, the nation’s foremost abortion provider.

Accepting membership in the world-government-promoting Council on Foreign Relations in 1966, he never ceased agreeing with its desire to eliminate national sovereignty in favor of United Nations rule over the planet. In 1991, he told a convocation at Notre Dame that he supported the “new world order” that would include strengthening the UN, providing it with its own military arm, and divesting the United States and other permanent Security Council members of veto power over Security Council resolutions. The CFR rewarded him for his loyalty to its goals by naming him one of its directors (1976-1985) and naming him chairman of its Membership Committee, a post he held for several years.

When the most pro-abortion president in our nation’s history, Barack Obama, received the invitation to deliver the 2009 commencement address at Notre Dame, President Emeritus Theodore Hesburg sought to defuse widespread protests aimed at the university’s president by defending an outspoken pro-Obama faculty member and publicly agreeing with the plan that included granting Obama an Honorary Degree.

Father Hesburg’s career clearly indicates that he was un-American, un-Catholic, and unworthy of the adulation he regularly received. He stood in sharp contrast to Charles Rice, who once told this writer, “I don’t approve of what Notre Dame now stands for. My efforts, so far, have kept the Law School a good place for people to send their sons and daughters. I don’t have a similar feeling about the undergraduate school.”