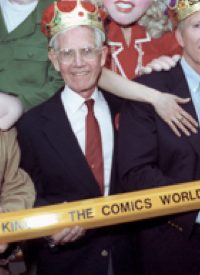

Beginning in 1960, Keane drew the one-panel cartoon, carried today in nearly 1,500 newspapers, that featured cherubic siblings Billy, Jeffy, Dolly, and P.J., along with their patient and loving parents. The cartoon, which focused on mundane and familiar family settings and situations, was by far the tamest piece in the daily comics, entertaining readers “with a simple but sublime mix of humor and traditional family values,” reported the Associated Press. Keane told the AP in a 1995 interview that the cartoon’s popularity was tied to its consistency and simplicity. “It’s reassuring, I think, to the American public to see the same family,” he said.

Even though he kept up with the times, adding relevant pop culture references to keep the cartoon timely, “the context of his comic was timeless,” noted AP. “The ghost-like ‘Ida Know’ and ‘Not Me’ who deferred blame for household accidents were staples of the strip.” Other supporting cartoon cast members included the family’s pets, Barfy and Sam the dogs, along with Kittycat.

Keane called the daily comics “the last frontier of good, wholesome family humor and entertainment,” adding, “On radio and television, magazines and the movies, you can’t tell what you’re going to get. When you look at the comic page, you can usually depend on something acceptable by the entire family.”

The cartoonist’s son, Jeff Keane (inspiration for the “Jeffy” character), who had been drawing the comic for the past few years as his father enjoyed retirement, said he thought the comic continued to thrive throughout the decades because, deep down, most people value family. He emphasized that his father’s creativity was crucial to that success. “It was a different type of comic,” he told AP, “and I think that was my dad’s genius — creating something that people could really relate to and wasn’t necessarily meant to get a laugh. It was more of a warm feeling or a lump in the throat.”

Born in Philadelphia in 1922, Keane taught himself to draw in high school, and began perfecting his craft as a cartoonist in the Army, where he met his wife, Thelma, while serving in Australia. In the early 1950s, he began drawing a one-panel cartoon called “Channel Chuckles,” that capitalized on the humor Keane found with television, which was just beginning to pop up in American homes. In one comic, for example, Keane had a young mother seated in front of a television with a wailing baby perched on her lap. “She slept through two gun fights and a barroom brawl — then the commercial woke her up,” the exasperated mom quips to her husband.

With a move to Arizona in 1958, Keane soon found the cartoon niche that, for the next 50 years, Americans could count on for its simple humorous and consistent wholesome values, regardless of the changing cultural trends. The formula was simple: Keane based “Family Circus” on his and Thelma’s own growing family. “I never thought about a philosophy for the strip — it developed gradually,” Keane told a local Arizona newspaper, the East Valley Tribune, in 1998. “I was portraying the family through my eyes. Everything that’s happened in the strip has happened to me.”

Keane said his wife, who died in 2008 after battling Alzheimer’s disease, was largely responsible for his success, working as his business manager and negotiating a deal that made him one of the first syndicated cartoonists to retain the rights to his cartoons. “There was nothing that I did in the cartoon world or in the business world that she wasn’t the instigator of, and she certainly deserves all the credit that I get credit for,” Keane told the East Valley Tribune at her death.

Of course, she was also the inspiration for “Mommy” in Keane’s famed comic. In fact, Keane recalled, she looked so much like the cartoon character, that, early on, “if she was in the supermarket pushing her cart around, people would come up to her and say, ‘Aren’t you the Mommy in ‘Family Circus?’ and she would admit it.”

While Keane’s work was known for being inconspicuous and underplayed compared to some of the flamboyant creations on the cartoon pages of daily newspapers, he nonetheless had the respect of fellow cartoonists, not the least of whom was “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz, who told AP that “Family Circus” worked for one simple reason: It was funny. Schulz also liked the cartoon strip because it shared the same values he strove to include in his own legendary strip. “I think we share a care for the same type of humor,” Schulz said in a 1995 AP interview. “We’re both family men with children and look with great fondness at our families.”

Nonetheless, Keane told the Los Angeles Times in 1990, his goal was not merely to make his cartoons funny. “Many of my cartoons are not a belly laugh,” he explained. “I go for nostalgia, the lump in the throat, the tear in the eye, the tug in the heart.”

Andrew Farago, curator of the Cartoon Art Museum of San Francisco, told the Times that millions of readers found something in Keane’s comics to which they could relate. “Kitchens coast to coast have ‘Family Circus’ strips cut out of the newspaper on them, because you will be reminded of something that your sister did or what your father said at breakfast,” he said.

The New York Times cited examples of some Keane classics, such as the “Family Circus” cartoon published on September 10, 1964, in which Mommy is gazing at a grocery list in her handwriting posted on the kitchen wall, with the items: “Cereal, tea, soap.” Underneath her neatly scribed list, in a sloppy child’s pen, are added: “Ice cream, cookies, plastic soldiers” — with all the s’s reversed.

Nearly 45 years later, Keane was still on his game with a cartoon published on January 22, 2008, in which Mommy — not aged a day — stands at the kitchen stove as one of the youngsters tells his sister, “Mommy’s cooking my favorite dinner. It’s called ‘leftovers.’”

Jeff Keane noted that the 50 years of memorable family cartoons were nothing less than his father’s interpretation of what happened in their home every day. “He was just our dad,” the younger cartoonist recalled to AP News. “The great thing about him is he worked at home, we got to see him all the time, and we would all sit down and have dinner together. What you see in the `Family Circus’ is what we were and what we still are, just different generations.”

Photo of Bil Keane: AP Images