“In arguing for the right of the terminally ill to choose how they die,” reported the Times, “Dr. Kevorkian challenged social taboos about disease and dying while defying prosecutors and the courts.” Convicted of second degree murder in 1999 in the death of the final person he helped to commit suicide (one of an estimated 130), Kevorkian ultimately spent eight years of a 25-year sentence in prison, being released only after he promised to give up his gruesome mission.

Fieger explained that Kevorkian felt “it was the duty of every physician to alleviate suffering, and when the circumstance was such that there was no alternative, to help that patient to end their own suffering.”

But the American Medical Association, which had another take on Kevorkian’s “mercy killing” campaign, called him in 1995 “a reckless instrument of death [who] poses a great threat to the public.” Similarly Diane Coleman, a disabled person and head of the right-to-life group Not Dead Yet, said that it was “the ultimate form of discrimination to offer people with disabilities help to die without having offered real options to live.”

Coleman recalled that as a disabled woman, “I was disgusted and alarmed with how easily society accepted and even applauded Kevorkian’s ‘help’ in the suicides of disabled women.” She said that like many other disabled individuals, “I’ve gone through periods of isolation and desperation — and was lucky to have friends see that I needed support.” She noted that when a disabled person indicated she wanted to die, it seemed that “no one — not the Kevorkian juries, not the press, not even many people in the general public — look for reasons beyond the wheelchair the woman sits in as a valid reason for wanting to die.”

In 1990 Kevorkian performed his first acknowledged assisted suicide, when he helped a woman suffering with Alzheimer’s disease to end her life, lending her a machine he had designed that allowed her to inject herself with lethal medication. While he was later charged with first-degree murder, the charges were dropped.

The day after the suicide Kevorkian told the New York Times, “My ultimate aim is to make euthanasia a positive experience. I’m trying to knock the medical profession into accepting its responsibilities, and those responsibilities include assisting their patients with death.”

In its reporting on his death, Reuters recalled that “Kevorkian made a point of thumbing his nose at lawmakers, prosecutors, and judges as he accelerated his campaign through the 1990s, using various methods including carbon monoxide gas. Often, Kevorkian would drop off bodies at hospitals late at night or leave them in motel rooms where the assisted suicides took place.”

Colleagues first gave Kevorkian the nickname “Dr. Death” during his medical residency in the 1950s when he volunteered for the night shift at the Detroit Receiving Hospital so he could be on duty when more people were dying. In a 2010 interview he told Reuters that the world had a hypocritical view of assisted suicide. “If we can aid people into coming into the world, why can’t we aid them in exiting the world?” he wondered.

In 2010 HBO capitalized on Kevorkian’s notoriety, producing a dramatization of his bizarre story entitled You Don’t Know Jack, with Al Pacino in the starring role. Pacino, who won both an Emmy and a Golden Globe Award for the effort, expressed his pleasure at being given the opportunity “to portray someone as brilliant and interesting and unique” as Kevorkian.

While Kevorkian said he liked the movie “and enjoyed the attention it generated,” reported the Guardian newspaper, he doubted “it would inspire much action by a new generation of assisted-dying advocates.” Said the doctor: “You’ll hear people say, ‘Well, it’s in the news again, it’s time for discussing this further.’ No it isn’t. It’s been discussed to death. There’s nothing new to say about it. It’s a legitimate ethical medical practice, as it was in ancient Rome and Greece.”

Although assisted suicide has, thankfully, not gained the wide legal recognition Kevorkian had hoped for, one state, Oregon, did enact a law in 1997 making it legal for a physician to help terminally ill patients end their lives by prescribing lethal drugs for them. In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the state’s Death With Dignity Act “protected assisted suicide as a legitimate medical practice,” reported the New York Times.

Most of the news accounts on Kevorkian’s death gave the controversial doctor a pass on the fact that he had criminally assisted over 100 people to commit suicide, and was as responsible as anyone for the evolution of such an act in the minds of millions from murderous to “humanitarian.”

One expert who put Kevorkian’s legacy in a more realistic perspective, however, was bioethics specialist Wesley Smith, who noted in a 2006 Weekly Standard article that some 70 percent of the individuals whom Kevorkian helped to kill were not even terminally ill. “Most were disabled and depressed, wrote Smith. “At least five had no discernible illnesses upon autopsy.”

Writing on his blog site after the doctor’s death, Wesley reflected that “Kevorkian was a disturbed man who, I fear, understood his society—and the media—all too well. And that may be his legacy. He perceived how far some will bend to rationalize even the most egregious wrongdoing or advocacy if the excuse is relieving suffering. Time will tell if he was also a prophet of a dark utilitarian society to come.”

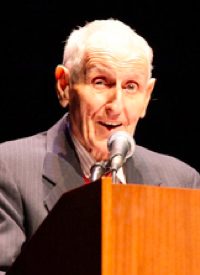

Photo: Jack Kevorkian