The World Trade Center bombers had some curious connections.

Following the outbreak of communist revolutions across Europe in 1848, Frederic Bastiat, a French champion of free enterprise, took note of the fact that many of his government’s supposedly anti-communist policies were actually creating communist-style controls over the economic and political life of his country. As a member of the French Assembly, Bastiat chided his government for “concocting the antidote and the poison in the same laboratory” and for devoting “half of its resources to destroying the evil it has done with the other half.”

Our own federal government’s ever-escalating “war” on terrorism displays similar dynamics. The same Clinton administration that urges the expansion of federal power — and the contraction of personal liberties — in the struggle against terrorism has eagerly courted the Syrian terror regime and has played host to representatives of the IRA, the Russian mafia, the Red Chinese arms-smuggling industry, and Muslim terrorist factions. This same bizarre duality is apparent in the administration’s domestic “anti- terrorism” initiatives. As the November 11 Washington Post reported, “Since the Oklahoma City bombing [of] April 19, 1995, the FBI, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF), and other federal law enforcement agencies have embarked on a preemptive strategy to uncover domestic terrorist conspiracies while they are in the planning stages. This strategy requires aggressive and potentially controversial tactics as investigators infiltrate groups and bring charges on the basis of allegedly criminal plans that are conceived but not carried out.”

Federal Entrapment

The new federal anti-terrorism strategy has resulted in the arrest, prosecution, and (in some cases) conviction of militia members on conspiracy charges in Georgia, Arizona, Washington, and West Virginia. However, it has also produced convincing evidence that the federal informants have acted as agents provocateurs, urging militia members to undertake potentially criminal actions.

In the case of the “Viper Team” in Phoenix, for example, it was a “confidential informant” who infiltrated the militia and suggested that the group rob banks in order to finance its activities. In the Georgia militia case, federal informants who had infiltrated the militia urged its leaders to manufacture pipe bombs; after failing to win support for their idea, the informants planted pipe-bomb components on property belonging to the militia group’s leaders.

In the more recent case of the Mountaineer Militia in West Virginia, an FBI informant — posing as an arms dealer — asked militia leader Floyd Ray Looker to sell him plans of a local FBI computer facility for $50,000. Although U.S. Attorney William D. Wilmoth has acknowledged that “the facility itself was never in any direct danger” from the Mountaineer Militia, seven members of the group were arrested on terrorism charges on October 11 in what the Washington Post called an “unprecedented use of a new anti-terrorism law.” None of the militias targeted for “preemptive” federal action has a track record of violence. What would happen if federal agents were to use the same tactics on an authentic terrorist cell — one composed of genuinely ruthless people possessing both the will and the means to carry out lethal acts of political violence?

Bungling or Abetting?

One answer was provided by the February 26, 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City, an attack that killed six Americans, wounded more than a thousand others, inflicted $500 million in damage, and dispelled America’s sense of immunity to international terrorism. The leaders of the radical Islamic network responsible for the bombing, who later planned a campaign of urban terrorism which could have claimed the lives of thousands of Americans, were given financial aid and training by the CIA. Furthermore, at several critical junctures where the conspiracy could have been exposed and its leaders arrested, federal law enforcement either ignored that network or actually provided crucial help to it.

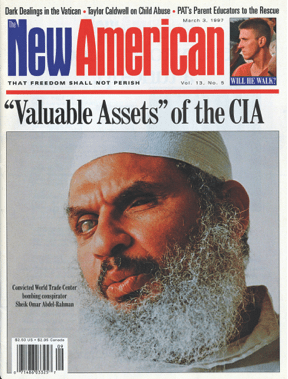

The central figure of that terrorist network was Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman (shown above), the “spiritual leader” of the Egyptian extremist group Gama al-Islamiya. In January 1996, Sheik Omar was convicted of “seditious conspiracy” and sentenced to life in prison for his part in planning the bombing; his nine co-conspirators were handed sentences ranging from 25 years to life. The sheik’s defense team attempted to depict the prosecution of their client as an instance of anti-Muslim persecution. However, Sheik Omar’s religious vocation, unlike that of the vast majority of devout, peaceful Muslims, was steeped in violence and hatred.

Sheik Omar and his followers were arrested in June 1993, six months after the Trade Center bombing; at the time of the arrest, some of the plotters were literally mixing chemicals to manufacture bombs. Following the January 1996 convictions of Sheik Omar and his disciples, Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew C. McCarthy declared, “There is a support system for terrorism in the United States whose designer is Sheik Abdel-Rahman…. [It would be] naive to think it has been destroyed.” According to Two Seconds Under the World, an account of the Trade Center bombing by New York Newsday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative team of Jim Dwyer, David Kocieniewski, Deidre Murphy, and Peg Tyre, Sheik Omar’s followers have established cells in Texas, California, Illinois, and Michigan. Although Sheik Omar may have been the “designer” of this terrorist network, its “support system,” as we will see, included the CIA, the U.S. Army, and — arguably — federal law enforcement agencies.

CIA Connection

Sheik Omar, who was accused of complicity in the plot to assassinate Anwar Sadat, has devoted his adult life to the overthrow of the secular Egyptian government and the propagation of his variety of Islam. In 1987, the U.S. State Department placed Sheik Omar’s name on its “watch list” of non-Americans believed to be involved in terrorism. However, this did not prevent the CIA from enlisting Sheik Omar as a “valuable asset” in covert operations involving the Afghan mujahideen during the 1980s.

Between 1980 and 1989, the CIA pumped more than $3 billion in aid into the mujahideen, the Islamic resistance to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The mujahideen’s rank and file was composed of brave and motivated men who displayed astonishing courage in their effort to evict the Soviets from Afghanistan. However, as veteran foreign correspondent Kurt Lohbeck documented in his study Holy War, Unholy Victory: Eyewitness to the CIA’s Secret War in Afghanistan, the CIA invested most of its aid in the least combat-worthy and most anti-American factions of the mujahideen. Among the CIA’s dubious beneficiaries was Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman.

Writing in the May 1996 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, foreign correspondent Mary Anne Weaver pointed out that it was in Peshawar, Pakistan, in the late 1980s that Sheik Omar “became involved with U.S. and Pakistani intelligence officials who were orchestrating the war” against the Soviets, and that the “sixty or so CIA and Special Forces officers based there considered him a ‘valuable asset’ … and overlooked his anti-Western message and incitement to holy war because they wanted him to help unify the mujahideen groups.”

Sheik Omar and his associates created an institution in Peshawar, Pakistan, called the Service Office, which recruited Muslims from around the world as volunteers to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. However, as Weaver pointed out, “Money flowed into the Service Office from the Muslim Brotherhood” — one of the most radical and violently anti-Western factions of the Pan-Islamic movement. Along with hundreds of millions of dollars from Saudi Arabia, Muslim Brotherhood money was distributed through branches of the Service Office in Europe and the United States, thereby providing a ready slush fund for terrorists and anti-Western agitators. While the Service Office sluiced money into the coffers of terrorists, Sheik Omar preached his gospel of jihad in Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, and in Islamic population centers in Turkey, Germany, England, and even the United States — despite his listing on the State Department’s “watch list.” Sheik Omar’s CIA-aided access to the United States continued after the Soviets vacated Afghanistan in 1989.

On May 10, 1990, Sheik Omar was granted a one-year visa from a CIA agent posing as an official at the U.S. Consulate in Khartoum, Sudan, and he arrived in New York in July 1990. In November of the same year Sheik Omar’s visa was revoked, and the State Department advised the Immigration and Naturalization Service to be on the lookout for him. So attentive was the INS to this advisory that it granted Sheik Omar a green card just five months later.

Terrorist Network

The American-based radicals who sponsored Sheik Omar’s 1990 trip to the U.S. included Mahmud Abouhalima, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and a CIA-supported veteran of the Afghan campaign. Abouhalima had networked with radical Muslims and American Black Panthers since the mid-1980s. Also helping to make arrangements for the sheik’s visit was Mustafa Shalabi, the Brooklyn-based director of Alkifah, a support fund for mujahideen fighters. Another leader of Sheik Omar’s American network was El Sayyid Nosair, an Egyptian expatriate who was later acquitted of the 1990 murder of Jewish militant Rabbi Meir Kahane.

Abouhalima and Nosair were eventually among those convicted of conspiring with Sheik Omar to wage urban warfare in the United States, and in that campaign they made use of skills imparted to them by the CIA and the U.S. military. During the conspiracy trial, attorneys for Sheik Omar and his disciples introduced a file documenting that in 1989, the U.S. Army had sent Special Forces Sergeant Ali A. Mohammed to Jersey City to provide training for mujahideen recruits, including Abouhalima and Nosair. But even as Abouhalima and Nosair underwent that training, according to Two Seconds Under the World, the FBI had them under surveillance as possible terrorists. Although Sheik Omar provided “spiritual” guidance to his network, the Abu Nidal-trained Nosair was the conspiracy’s field commander, and Abouhalima was his most important lieutenant.

The FBI engaged in a curiously timed fit of incompetence when the opportunity arose for a preemptive strike against Sheik Omar’s network. Following the shooting of Rabbi Meir Kahane in November 1990, the FBI seized and impounded 49 boxes of documents from Nosair’s New Jersey apartment; the cache included bomb-making instructions, a hit list of public figures (including Kahane), paramilitary training materials, detailed pictures of famous buildings (including the World Trade Center), and sermons by Sheik Omar urging his followers to “destroy the edifices of capitalism.”

But the FBI made none of the evidence available to New York City Assistant District Attorney William Greenbaum, who prosecuted the case. In fact, the FBI ignored the material until after the Trade Center bombing in 1993. Veteran radical lawyer William Kunstler offered his services as Nosair’s defense attorney. Kunstler deployed his entire arsenal of sophistries, and presiding Judge William Schlesinger of the New York State Supreme Court granted Kunstler extraordinary procedural latitude (including the privilege of dismissing white potential jurors on racial grounds). Schlesinger’s penchant for Kunstler was so pronounced that he invited the notorious Marxist barrister to a Christmas party in his chambers during jury deliberations.

Hamstrung by the FBI’s decision to withhold the evidence collected at Nosair’s apartment, and stymied by Judge Schlesinger’s visible partiality toward the defense, prosecutor Greenbaum was unable to secure a murder conviction against Nosair. When the verdict was announced on December 20, 1991, Kunstler was carried triumphantly away from the courtroom on the burly shoulders of Muslim Brotherhood terrorist Mahmud Abouhalima. Nosair, who was convicted on lesser firearms-related charges, began a seven-year term in Attica prison, where he continued to direct the affairs of Sheik Omar’s terrorist network.

The violence pulsating through Sheik Omar’s network was not directed solely at predictable enemies like Kahane. By March 1991, Sheik Omar and his associates had seized control of the Alkifah fund, which had by then swollen to an estimated $2 million — and Shalabi, the fund’s manager, was found murdered shortly after a confrontation with three of Sheik Omar’s disciples. The CIA-originated fund helped finance Nosair’s trial defense. It was also used to procure many of the bomb components that were assembled under the expert supervision of Afghan terrorist Ramzi Yousef, who was imported by the Sheik Omar network in late 1992.

FBI Foreknowledge

Yousef was convicted on September 8, 1996 of plotting a 48-hour campaign of bombings against American commercial flights over the Pacific Ocean. The campaign would have targeted a total of 12 jetliners and as many as 4,000 passengers. Yousef is also accused of carrying out the December 11, 1994 bombing of a Philippine jetliner that killed a Japanese passenger, as well as plotting to assassinate Pope John Paul II. Yousef met Abouhalima in Afghanistan in 1988, and it was Abouhalima who brought the Afghan terrorist to the United States in September 1992 on behalf of Sheik Omar’s network.

Shortly after Yousef’s arrival, the FBI subpoenaed two dozen of Sheik Omar’s followers and questioned them about the sheik, Nosair, and Abouhalima. However, no arrests were made, no grand jury investigation was launched, and the FBI chose to downgrade its scrutiny of Omar’s network — just as plans were being finalized for the Trade Center bombing. This curious decision is even more peculiar in light of the fact that the FBI had obtained intelligence on the network’s capabilities and intentions from Emad A. Salem, a former Egyptian Army officer and FBI informant who served as Omar’s security guard.

Salem’s relationship with the FBI was turbulent, and there were suggestions of impropriety in his personal contacts with FBI handler Nancy Floyd. However, he had repeatedly warned the FBI that Nosair was running a terrorist ring out of his prison cell, and he had supplied detailed descriptions of the Sheik Omar network’s plans. But the FBI was doubtful of Salem’s reliability and severed its contacts with him seven months before the bombing.

In the aftermath of the Trade Center bombing, the FBI renewed its association with Salem, paying him a reported $1 million to infiltrate Sheik Omar’s group once again. Salem secretly recorded many of his conversations with law enforcement agents, including exchanges in which it was revealed that the FBI had detailed prior knowledge of the Trade Center bomb plot. According to Salem, the FBI had planned to sabotage the Trade Center bomb by replacing the explosive components with an inert powder. The October 28, 1993 New York Times reported that in one conversation Salem recalled assurances from an FBI supervisor that the agency’s plan called for “building the bomb with a phony powder and grabbing the people who [were] involved in [the plot].” However, the supervisor, in Salem’s words, “messed it up.”

Salem recalled that when he expressed a desire to lodge a protest with FBI headquarters, he was told by special agent John Anticev that “the New York people [wouldn’t] like the things out of the New York office to go to Washington, DC.” Unappeased, Salem rebuked Anticev: “You saw this bomb went off and you … know that we could avoid that…. You get paid, guys, to prevent problems like this from happening.”

Perhaps the most remarkable illustration of the depth of the FBI’s knowledge of the Sheik Omar network came after the World Trade Center bombing, when the Bureau employed Salem’s services as an informant once again. As the Wall Street Journal reported, from March to June 1993 Salem “helped organize the ‘battle plan’ that the government alleged included plots to bomb the United Nations and FBI buildings in New York, and the Holland and Lincoln tunnels beneath the Hudson River. Working with a charismatic Sudanese man named Siddig Ali, a follower of Sheik Omar, Mr. Salem recruited seven local Muslims to scout targets, plan tactics and obtain chemicals and electrical parts for bombs.” By the time the FBI closed in on the plotters on June 23, it had literally hours of videotapes documenting the conspiracy in intimate detail — including footage of conspirators mixing fertilizer and diesel fuel to build a bomb.

Predictably, defense attorneys for Sheik Omar and his followers insisted that Salem’s actions amounted to entrapment. While the court rejected this defense, the FBI’s proficiency at using Salem to assemble a radical Muslim terrorist cell is unsettling, to say the least. Clearly, Salem knew his way around the sheik’s network, and was well-versed in the techniques of terrorism; just as clearly, the FBI knew how to make use of Salem’s abilities. It is difficult to believe that the FBI was incapable of cracking down preemptively on the sheik’s followers before the Trade Center bombing.

Poison and Antidote

However, the fact that Sheik Omar’s network consistently benefited from the actions of the federal government — from direct CIA aid to instances of peculiar neglect by the FBI — suggests that the cabal should be considered as much a creature of our federal government as it was a creation of a particular strain of Muslim extremism. Furthermore, the influence and activities of Sheik Omar’s co-conspirators are not limited to the United States.

As Mary Anne Weaver pointed out in The Atlantic Monthly, “the CIA helped to train and fund what eventually became an international network of highly disciplined and effective Islamic militants — and a new breed of terrorists as well.” According to Weaver, the CIA’s handiwork is on display across the Middle East — in the December 1995 car bomb attack in a crowded market in Peshawar, Pakistan, that killed 36 people and wounded 120 more, and also in two nearly identical car bombings in November 1995 that targeted U.S. military advisors in Saudi Arabia and the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan. The same network could also be considered a prime suspect in last summer’s unsolved terrorist attack on U.S. troops in Daharan, Saudi Arabia, terrorist bombings in Algeria and the Philippines, and perhaps even the downing of TWA Flight 800. Weaver quoted a former U.S. diplomat who told her, “The common element in all these attacks — whether in Cairo or Riyadh, Islamabad or Algiers, Europe or New York — is today’s equivalent of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade” — namely, a CIA-trained terrorist network.

Some intelligence analysts describe the emergence of that network as an example of “blowback” — unintended negative fallout from a covert operation. However, a more accurate analysis might make use of Frederic Bastiat’s metaphor of government creating the poison and the antidote in the same laboratory. The same power elite that created the “poison” of the post-Afghanistan terrorist network stands poised with an equally dreadful “antidote.” As Richard Haass, director of national security programs at the influential Council on Foreign Relations, asserted in a Washington Post op-ed column, the war against terrorism will require “a willingness to compromise some of our civil liberties, including accepting more frequent phone taps and surveillance. Those who would resist paying such a price should keep in mind that terrorism could well get worse in coming years.”

In such fashion, American citizens will pay the price for evils nurtured by a government that poses as their protector.