World AID Programs Don’t Work

Poor people around the world often starve to death — that’s a fact of life. Starving is a lousy way to die — that’s also a fact.

Here’s what it feels like to starve, according to an article by a prisoner who went on a hunger strike: For the first handful of days, you feel constantly hungry — empty. Then the stomach shrinks so that you don’t feel the emptiness, but in a short time, the weakness begins — movements are slower; energy is way down; and getting up quickly causes dizziness and nausea. The sense of smell becomes acute, but vision and hearing begin to fail. The body becomes gaunt, and blood vessels burst in the arms and face. Blurred and double vision begin, and the skin simply breaks open. At this point, starvation becomes painless until the retching begins, with the feeling that a bowel movement must be made, which is agonizing. Shortly after that, a coma sets in, and without medical intervention, death will come.

Short of death, starvation causes stunted growth, easier disease transmission, poor brain development in children, and more.

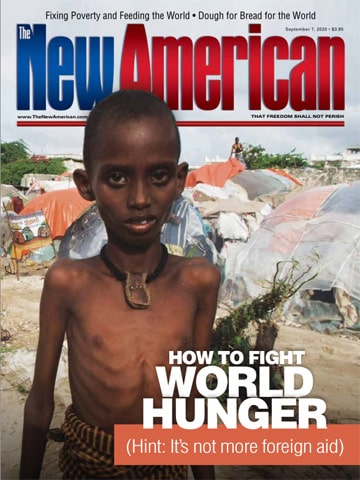

When public aid agencies are seeking funds, pictures of Third World starvation speak thousands of words. And in response to the pictures of starving people, many people in the developed world push their governments to send tax monies to public aid entities to help the poor. Those First Worlders desperately want to do something to help, and it is what they can do.

But while orchestrating giving to public aid entities may make the First World citizens feel better, their efforts will likely not help the poor — in fact, their efforts are likely to hurt the poor.

Graham Hancock, formerly a correspondent covering East Africa for the left-wing publication The Economist, wrote a book about the folly of foreign aid entitled Lords of Poverty: the Power, Prestige, and Corruption of the International Aid Business. Therein he states:

Africa contains many lessons for the aid lobby. It [Africa] has lost the self-sufficiency in food production that it enjoyed before development assistance was invented and, during the past few decades, has become instead a continent-sized beggar hopelessly dependent on the largesse of outsiders — per capita food production has fallen in every year since 1962. Seven out of every ten Africans are, furthermore, now reckoned to be destitute or on the verge of ‘extreme poverty’, with the result that the continent has the highest infant mortality rates in the world, the lowest average life-expectancies in the world, the lowest literacy rates, the fewest doctors per head of population, and the fewest children in school. Tellingly, during the period 1980 to 1986 when Africa became — by a considerable margin — the world’s most ‘aided’ continent, GDP per capita fell by an average of 3.4 per cent per annum.

After seeing firsthand how public foreign aid was misused, he concludes:

To continue with the charade seems to me to be absurd. Garnered and justified in the name of the destitute and the vulnerable, aid’s main function in the past half-century has been to create and then entrench a powerful new class of rich and privileged people. In that notorious club of parasites and hangers-on made up of the United Nations, the World Bank and bilateral agencies, it is aid — and nothing else — that has provided hundreds of thousands of “jobs for the boys” and that has permitted record-breaking standards to be set in self-serving behaviour, arrogance, paternalism, moral cowardice and mendacity. At the same time, in the developing countries, aid has perpetuated the rule of incompetent and venal men whose leadership would otherwise be non-viable; it has allowed governments characterized by historic ignorance, avarice and irresponsibility to thrive; last but not least, it has condoned — and in some cases facilitated — the most consistent and grievous abuses of human rights that have occurred anywhere in the world since the dark ages.

Moreover, he added, “Such suffering … often occurs not in spite of aid but because of it.” (Emphasis in original.)

Yet public righteousness in the global community, then and now, goes hand in hand with the amount of money that governments give as foreign aid. Governments such as that in the United States — which actually gives more money than any other nation except China, but doesn’t give as a high a percentage of its GDP as some other countries’ governments — are chastised, while other countries such as little Sweden are praised for their generosity. (Note: Foreign aid from private sources in the United States is several times larger than public aid.) The implication given is that the aid is having a direct, positive effect on the poverty-stricken of the world, especially the malnourished; hence, aid, especially food-related aid, is equivalent to godliness.

Hancock wrote his book in 1989, but aid — in larger amounts than ever before — hasn’t ended or substantially changed, even though it hasn’t lifted the world’s poor from poverty or enabled them to feed themselves over its past, roughly, 70 to 80 years of existence. Keeping these facts in mind, let us examine the failing face of world aid programs — then and now.

Graham’s Gripes

In his book, Graham Hancock covers case after case in the past wherein aid actually made the lives of the world’s poor worse, and he explains why aid was/is far from helpful (though the following list is not all-encompassing):

- Very little aid reaches the poor because aid workers for such entities as the UN and the World Bank seldom spend much time with the poor figuring out their problems.

- Very few aid workers have any expertise in the problems they are supposedly trying to solve, and they are usually too vain to ask the opinions of the needy.

- Most money supposedly spent on “the poor” usually goes toward Western experts, or toward goods purchased in Western countries.

- Most aid money that does make it to Third World countries gets siphoned off for use by governmental elites.

- Food aid is not usually sent when it is needed, and when food aid is sent, it tends to impoverish local farmers by glutting markets so they can’t sell their produce.

- Aid abets corrupt governments, keeping them in power and aiding them to steal land and money from the poor.

- The World Bank and UN are graft-ridden and loaded with self-indulgent hacks who only really care about their own welfare.

- The World Bank not only demands repayment of loans with interest from poor countries, but the loans usually come with strings attached, making the countries beholden to their international masters.

Hancock’s first notable example showing the fallacies of public foreign aid was the August 1988 flooding in the Sudan: After the River Nile overflowed, “overnight, more than a million people were rendered homeless in Khartoum, the capital city,” many “without any kind of food or shelter.” Aid agencies appealed in Western countries for money, and millions of dollars were pledged, yet “two weeks after the flooding … almost no tangible signs of the relief effort could be seen on the ground: a dozen or so plastic sheets here, a few blankets from the Red Crescent Society there, and a grain-distribution station with just twelve sacks of flour in hand. Visiting reporters were proudly shown a newly erected camp of 300 tents provided by Britain: for reasons that no one on the spot could explain, all the tents turned out to be empty and under armed guard — even though tens of thousands of homeless people were milling about on mudflats nearby.” Eighty-five relief flights had arrived from the United States and Europe, but only 400 tons of food, against an estimated need of 12,000 tons. And part of the food sent was a container of fresh meat, despite a lack of refrigeration; “by contrast much more durable — and necessary items — like clothing, soap and hospital tents were almost completely missing from the relief deliveries during the first two weeks.”

Hancock found that such poor planning by aid agencies, rather than being an anomaly, was the rule. In the 1950s and 1960s, the World Bank helped fund the “giant Akosombo Dam on the Volta River” in Ghana. The damn provided electrical power for a U.S.-owned alumina smelting plant, and “benefitted wealthy Ghanians,” but hurt the poor. The power lines ran over their villages, not to them; diseases spread — tens of thousands got river blindness (onchocerciasis), caused by black flies that breed in fast-running dam discharges; and prime farmland behind the dam was flooded. Similar types of problems happened in Pakistan, India, Haiti, China, Nigeria, Brazil, Paraguay, and more. Then there were a multitude of projects built — such as a rice-hull-fed thermal power plant in the Philippines and a solar drier in the Dominican Republic — that couldn’t be run owing to a lack of local expertise or the funds needed to keep operating, especially if something broke down.

He noted that the World Bank usually failed to support useful projects: “Year in year out, … and in true Soviet-factory style — this is precisely what the Bank continues to do. It is thus probably not entirely coincidental that, out of a representative sample of 189 projects audited worldwide, no less than 106 — almost 60 per cent — were found in 1987 either to have ‘serious shortcomings’ or to be ‘complete failures’. A similar proportion of these projects — including many judged in other senses to be ‘successes’ — were thought unlikely to be sustainable after completion.” And the World Bank performs worst in the poorest countries.

International aid agencies also commonly wreak havoc on the environment. In 1972, the World Bank “contributed $1.65 million to … finance cattle and sheep ranches in the environmentally sensitive western Kalahari. The project — which was eventually completed with a budget over-run of $2.9 million — resulted in dangerous overgrazing of the fragile savanna grasslands but, unfortunately, produced no benefits at all.” The World Bank tried again from 1977 to 1984, with the same result: desertification and monetary loss.

In several cases, aid agency-backed plans entailed relocating large groups of peoples, depriving them of livelihoods and often ruining the natural environment in the process. In addition to the uncounted masses who had to move when waters from dams flooded their homelands, Hancock lists a few other examples to make his point: “In Ethiopia’s Awash Valley, Afar nomads whose traditional dry-season pasture lands have been sown with cash crops and surrounded by barbed wire are today reduced to penury, their independence gone, their way of life shattered, their dignity destroyed as they queue in rags for food handouts. Brazilian Indians whose rainforests have been felled in the name of progress now face genocide; their unique knowledge and skills are about to be lost to mankind for ever. In Indonesia’s ‘thousand island’ paradise, tribal peoples are remorselessly being extinguished and priceless ecological resources turned to ash and mud amidst the folly of the largest resettlement programme in human history…”

As to the tragedy in Indonesia, from the 1970s through the 1990s, that country attempted “the world’s largest-ever exercise in human resettlement,” which was supported by the World Bank, USAID, FAO (the UN Food and Agriculture Organization), the World Food Programme, Catholic Relief Services, and some European governments, and it was a disaster. The plan was to move six to eight million peasant farmers from “overcrowded Java to the more thinly populated outlying islands of the vast archipelago.” Not only were hundreds of thousands of indigenous people on the outlying islands stripped of their property rights and often forcibly moved to make room for the new populace, when the jungles were slashed for farms, it was soon discovered that the soils were unsuitable for large-scale farming, so the relocated peoples often continued to slash and burn the tropical rainforests to sell the wood or they fled back to where they came from or they did the lowest of work to survive, such as prostitution — with venereal disease running rampant. A World Bank study found that the relocated people not only were poorer than they had been previously, the longer they lived in the new areas, the poorer they became.

Much of the destruction of the rainforest in the Amazon Basin in Brazil also came from a World Bank project that gave $250 million in funding to open up the rainforest with a new highway, supposedly to aid settlement of the rainforest by the poor.

The failure of the aid agencies is a logical consequence of the design of the agencies: They are set up so that mission failure results in their prosperity and longevity. They are similar to many government agencies, which exist for the most part to employ, enrich, and empower their workforce, rather than to actually serve society; and aid workers will do nearly anything to keep their jobs in perpetuity. In the case of aid agencies, their policy failures actually ensure the workers’ own livelihoods, and failed activities are only considered truly bad when the blunders make the national headlines.

The problems with public aid were unfixable in Hancock’s day, and remain so today. The entities exist not to serve the poor, but to use the poor.

At the UN, Hancock states, in referencing the likelihood that aid agencies would change for the better, the hierarchy is so complicated that every agency simply gets in the way of every other one. And waste is virtually never stamped out: “In 1982, at least 100 such programmes [programs deemed to be redundant or non productive] were judged by the Secretary General of the United Nations to be ‘elderly’, non-productive, or redundant by virtue of duplication. He recommended that all should be terminated, with an anticipated annual savings of $35 million. Four years and $140 million later, however, an independent study revealed that not one of these senile and unnecessary ‘pets’ had been put down.” Moreover, a whole host of committees have been created to construct organizational efficiency from UN chaos, but they have just made more unread paperwork. When a hard-hitting conference does find blame for a problem somewhere, the conference stands to get shut down by the countries it is reporting on.

Even when the UN created the UN Disaster Relief Office to make aid effective and coordinate aid among UN agencies, it failed utterly: “A study of the UN World Food Programme’s response to eighty-four emergencies showed that it took an average of 196 days for requests for assistance to be processed and the food delivered.”

Of course, complete incompetence or malfeasance didn’t/doesn’t cut into the upscale lifestyles of UN aid workers (or other public aid workers), especially the bosses.

In 1986, the Bank-Fund annual meeting, where all the important people in the aid business — both donors and recipient countries — met to talk about poverty, cost about $10 million, and participants stayed at the finest hotels and dined on such delicacies as crab cakes, caviar, smoked salmon, beef Wellington, lobster, duck, and more. As the author says, $10 million could have provided enough vitamin-A tablets to prevent 47 million children from risking sight impairment from nutrient deficiencies.

Meanwhile, aid workers were so commonly incompetent that much basic work needed to be outsourced. “Personnel and associated costs [at that time] absorb[ed] a staggering 80 per cent of all UN expenditures,” leaving not much for world development. “Thus, at every level of the multilateral agencies, maladjusted, inadequate, incompetent individuals are to be found clinging tenaciously to highly paid jobs, timidly and indifferently performing their functions and, in the process, betraying the world’s poor in whose name they have been appointed.”

Then, too, most of the money supposedly spent on “the poor” usually went toward Western experts, or toward goods purchased in Western countries. Hancock offers the following:

During the period 1960-70, for example — John F. Kennedy’s idealistic “First Development Decade” — studies showed that 99 per cent of all the funds provided by AID for development in Latin America were in fact spent in the USA, and on products that were priced on average 35 per cent above their world market value. Even today 70 cents out of every dollar of American “assistance to the Third World” never actually leave the United States.

In fact, the main countries that contribute to the UN Development Programme often get back in purchases from the program more money than they donate.

In regard to this, aid agencies often brag that they are boosting businesses in host countries, as well as helping the world’s most unfortunate, but since the aid projects are often more about figuring out ways to use goods that can be purchased in donating countries, the “aid” that does make it to Third World countries is usually meager or ineffective. Aid usually is about redistributing money to cronies in donating countries, not about helping the poor, and it is about causing poor countries to be indebted to and subservient to rich countries, not equality.

Hancock makes it clear that the entire edifice of public aid is held together by propaganda (the aid agencies not only toot their own horns, governments and media also do it for them) and secrecy (UNESCO doesn’t let staff talk about their experiences, even after they retire, and the World Bank is worse). The very fact that it is extremely difficult to get useful information from aid agencies about exactly how monies are used by the agencies — how much has been raised, how much is spent, where it is spent, what it is spent on, how recipients benefited — is a clear indication of both fraud and failure because, obviously, both upright charitable giving and true success of aid activities would not be hidden.

As more proof of failure, he says, “The very fact that development strategies do keep changing is a tacit admission of failure (or anyway lack of success) of earlier efforts.”

Up to the Present

Now, still, 30 years after Hancock published his book, public aid agencies have not worked themselves out of a job; they have been growing bigger and spending more money, and the employees have been living upscale lifestyles. And their fraud and failure is still evident in their opaqueness, their spending patterns, and their mismanagement.

National Public Radio (NPR), an entity that no one could ever accuse of being against big government, talked about this in its February 28, 2013 article “What Happened to the Aid Meant to Rebuild Haiti?”

After a devastating earthquake hit Haiti in 2010, governments and foundations from around the world pledged more than $9 billion to help get the country back on its feet.

Only a fraction of the money ever made it. And Haiti’s President Michel Martelly says the funds aren’t “showing results.”

Roughly 350,000 people still live in camps. Many others simply moved back to the same shoddily built structures that proved so deadly during the disaster.

Martelly says the relief effort is uncoordinated and projects hatched from good intentions have undermined his government. “We don’t just want the money to come to Haiti. Stop sending money,” [he said]. “Let’s fix it,” he says, referring to the international relief system. “Let’s fix it.”

Disaster specialist Dr. Tom Kirsch from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine agrees with Martelly. “Clearly we saved lives,” he says. “Clearly we put people in tents. Clearly we did all kinds of stuff. But at the same time the level of chaos and the overall ability to reach needy people, we don’t know how well we did.”

Kirsch, who’s been in Haiti several times since the quake, added, “We could have written a check to everyone in Haiti for — I don’t know — $10,000 a piece, which would support them forever rather than the way we spent it.”

Of the estimated $2.5 billion that actually got allocated for Haiti, little of that money actually was sent to Haiti. The NPR story noted:

Ninety-three percent of that money either went to United Nations agencies or international nongovernmental organizations, or it never left the donor government.

So you had the Pentagon writing bills to the State Department to get reimbursed for having sent troops down to respond to the disaster.

If we’re talking about reconstruction, it’s really a misnomer to think that relief aid was necessarily going to have the effect of rebuilding a country in any shape or form.

In a trifecta of admissions — considering that NPR promotes big government as the be-all and end-all of poverty solutions — NPR noted that aid agencies and foreign governments are a main reason Haiti is a Third World mess in the first place:

There are lots of places that have weak governments, but Haiti’s government is weak in a special way. It’s the product of so many years of aid going around the government and international efforts to undermine the government. Presidents being overthrown and flown out on U.S. Air Force planes and then reinstalled and then overthrown again. That left the Haitian government in such a weakened state.

Yet despite the obvious aid-agency failings and the obvious bilking of America’s public funds for well-connected U.S. businesses, which has been going on for decades (this is what is termed “crony capitalism,” instead of free market capitalism), most American groups and individuals who truly wish to combat poverty continue to call for “fixing the international aid system,” as did the NPR article. But as we said, the system is designed to be unfixable — by intent. (See the article on page 16.)

Photo credit: AP Images