The Original Earth Day

At the time, the first Earth Day may have seemed to many a major anti-litter or pro-conservation effort. But there was much more to it than that.

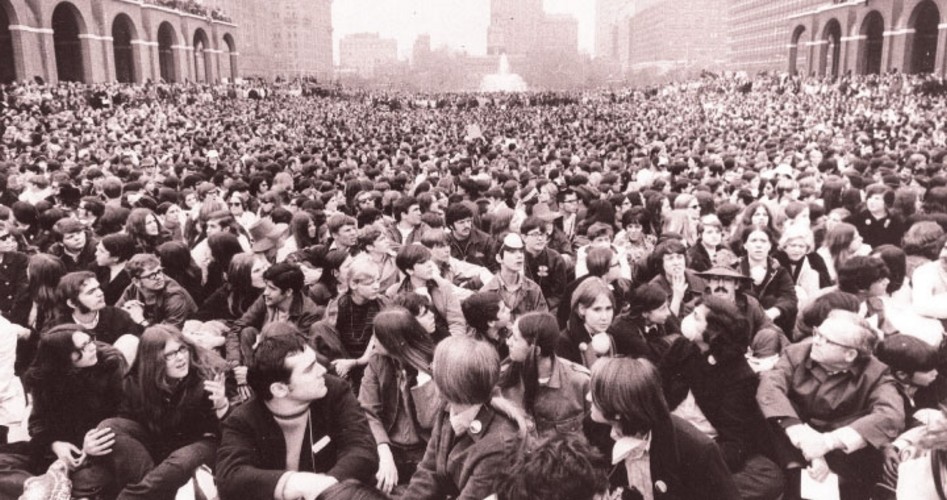

An estimated 20 million people participated in the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970 in college and high-school auditoriums, public parks, and other venues throughout the country. Earth Day founder Gaylord Nelson, who was a U.S. senator from Wisconsin at the time, recalled 20 years later in an article in the EPA Journal that his “major objective in planning Earth Day … was to organize a nationwide public demonstration so large it would, finally, get the attention of the politicians and force the environmental issue into the political dialogue of the nation.”

“It worked,” Nelson added. “By the sheer force of collective action on that one day, the American public forever changed the political landscape regarding environmental issues.”

Yet it was not the American public who changed the landscape, but Earth Day organizers and their patrons in the media, academe, and government who claimed to be operating on behalf of the people. Yes, many millions turned out for the 1970 Earth Day events. But many of these participants were simply pro-environment, without possessing much, if any, understanding of what the agenda behind Earth Day, which galvanized the modern-day environmental movement, actually entailed.

Denis Hayes, who was selected by Nelson to be the national coordinator for the original Earth Day, acknowledged in his April 22 Earth Day speech in Washington, D.C., “I suspect that the politicians and businessmen who are jumping on the environmental bandwagon don’t have the slightest idea what they are getting into. They are talking about filters on smokestacks while we are challenging corporate irresponsibility. They are busting with pride about plans for totally inadequate municipal sewage treatment plants; we are challenging the ethics of a society that, with only 6 percent of the world’s population, accounts for more than half of the world’s annual consumption of raw materials.”

Nelson himself acknowledged in a speech in Madison, Wisconsin, on Earth Day Eve that the envisioned environmental objectives “will require some tough decisions — political, economic, and social decisions that I am not certain the majority of people in this country support.” No kidding. As we shall see, the agenda advocated by Earth Day 1970 organizers amounted to shackling the planet in the name of saving it — hardly an agenda most Americans would have embraced in 1970, or even today, despite many decades of alarmist propaganda.

An excellent source for learning about the first Earth Day agenda is the 367-page manifesto entitled The Environmental Handbook: Prepared for the First National Environmental Teach-in, published by Ballantine Books in January of 1970. This writer remembers getting a copy from his high-school biology teacher that year, during the buildup to the big event on April 22. The handbook, comprised of a compilation of articles, is unabashedly socialist and internationalist — calling for authoritarian controls and the end of nationhood, ostensibly to save the planet. Another valuable source is the selection of Earth Day 1970 speeches that Earth Day organizers compiled in the book Earth Day — The Beginning, published shortly after Earth Day was held.

But before surveying the agenda itself, we should first take a look at the fright- peddling that the Earth Day organizers shamelessly engaged in to try to beguile Americans into accepting radical “solutions” they otherwise surely would reject.

Scary Scenarios

The Environmental Handbook employed fear to create the urgency to implement the agenda. The back cover warned ominously: “1970’s — the last chance for a future that makes ecological sense.” And in the Foreword, editor Garrett De Bell recalled the seemingly impossible task of writing a book during the short one-month time span allotted for that purpose: “We thought that the one-month deadline for the writing was impossible, that we could easily spend a year on it. But a year is about one-fifth of the time we have left if we are going to preserve any kind of quality in our world.” (Emphasis in original.)

Other Environmental Handbook contributors also wrote with the urgency that time was running out. One of them was Dr. Paul R. Ehrlich of Stanford University, the author of the alarmist 1968 best-seller The Population Bomb. The handbook included material excerpted from The Population Bomb as well as an article Ehrlich wrote for the now-defunct leftist political magazine Ramparts. In the latter, Ehrlich offered a scary scenario predicting what the world would be like if present trends continued. “The end of the ocean came late in the summer of 1979,” he lamented in his scenario. “By September, 1979, all important animal life in the sea was extinct. Large areas of coastline had to be evacuated, as windrows of dead fish created a monumental stench.”

In The Population Bomb, Ehrlich went so far as to predict that “in the 1970’s the world will undergo famines — hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” (Emphasis added.)

Anti-People

The alarmist agenda promoted by Earth Day organizers entailed heading off an environmental catastrophe by limiting man’s negative impact on the environment, and accomplishing that goal very much included limiting the number of people on the planet. “Too many cars, too many factories, too much detergent, too much pesticide, multiplying contrails, inadequate sewage treatment plants, too little water, too much carbon dioxide — all can be traced easily to too many people [Emphasis in original.],” said Ehrlich in The Population Bomb.

Ehrlich proposed controlling population “hopefully through a system of incentives and penalties, but by compulsion if voluntary methods fail.” Writing before Roe v. Wade, he candidly stated, “Abortion is a highly effective method in the armory of population control.” He added, “Many of my colleagues feel that some sort of compulsory birth regulation would be necessary to achieve [population] control. One plan often mentioned involves the addition of temporary sterilants to water supplies or staple food. Doses of the antidote would be carefully rationed by the government to produce the desired population size.”

Environmental Handbook editor De Bell recommended that, after halting world population growth, we “work toward reducing the current three and a half billion people to something less than one billion people.... This number, perhaps, could be supported at a standard of living roughly similar to that of countries such as Norway and the Netherlands at the present time.”

Environmental Handbook contributor Garrett Hardin, a biology professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, argued that a welfare state such as ours has an interest in controlling the breeding of families. “To couple the concept of freedom to breed with the belief that everyone born has an equal right to the commons [that is, the resources] is to lock the world into a tragic course of action,” Hardin said.

The handbook included a petition to President Richard Nixon that stated, “The population problem is more serious than any other problem, therefore, at least 10% of the defense budget must be allocated to birth control and abortion in the U.S. and abroad.”

In the minds of Earth Day 1970 promoters, man could no longer “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” He could not have dominion “over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing.” In fact, contrary to the Christian principle that man, unlike the rest of the animal kingdom, is created in the likeness and image of God, the stature of man according to the extreme environmentalist view is reduced to that of the rest of the animal kingdom. Earth Day founder Gaylord Nelson admitted as much when he said in an Earth Day speech in Madison, Wisconsin, “Man is just one of the creatures that the Lord put on this earth and is not more important than all the rest.”

In the Environmental Handbook, Lynn White, Jr., a history professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, went so far as to say that religion itself needed to be changed. “More science and more technology are not going to get us out of the present ecologic crisis until we find a new religion, or rethink our old one,” White claimed in the handbook. “We shall continue to have a worsening ecologic crisis until we reject the Christian axiom that nature has no reason for existence save to serve man.” Apparently, man is instead to serve nature.

Anti-Development and Anti-Freedom

The authoritarian agenda for reducing man’s impact on the environment included not only reducing the number of people but also reducing the impact each person has on the environment to a level that will not, in the view of the coercive utopians, exceed the carrying capacity of the Earth — what is now euphemistically called “sustainable development.”

Those who reside in the developed world, whose lifestyles are affluent compared to the undeveloped world, are viewed as environmental culprits whose standards of living must be reduced. In the Environmental Handbook, Rockefeller University professor René Dubos warned that “the destructive impact of each U.S. citizen on the physical, biological, and human environment is enormously magnified by the variety of gadgets and by the amount of energy at his disposal.” The solution? Handbook editor De Bell proposed a 25-percent reduction in total energy use in this country over the next 10 years.

America’s transportation system, with its heavy reliance on the private automobile, was decried by Earth Day 1970 promoters as being extremely energy inefficient and a major source of air pollution. In the Environmental Handbook, biophysicist Kenneth Cantor recommended programs “aimed at reduction of automobile usage to one-tenth of the present levels.” The handbook’s “Suggestions Toward an Ecological Platform” even recommended “outlaw[ing] the sale of reciprocating internal combustion engines by 1975.”

In general, America’s historic system of economic and political freedom, which has resulted in a cornucopia of wealth and prosperity making the American dream realistically achievable for everyday Americans, was viewed as toxic to the environment by Earth Day 1970 promoters. The compilation of speeches in Earth Day — The Beginning includes one given by Rennie Davis, who on April 22 in Washington, D.C., called for “an end to a system based on the prerogatives of private greed rather than social need.” Davis, who was one of the “Chicago Seven” defendants charged with conspiracy and inciting to riot in connection with the violent demonstrations that took place in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, proclaimed in his speech, “Earth Day is for the sons and daughters of the American Revolution who are going to tear this capitalism down and set us free.”

But U.S. Senator James Pearson of Kansas perhaps presented the Earth Day message more clearly and concisely than anyone else on April 22, 1970, when he stated in remarks included in Earth Day — The Beginning: “Profits must be cut, comforts reduced, taxes raised, sacrifices endured.”

Pro-World Government

The agenda advanced by the first Earth Day also included submerging the United States and other nations in a one-world government, based on the premise that environmental devastation and other problems transcending national boundaries cannot be adequately addressed without international controls.

The Environmental Handbook included a selection by Harper’s magazine contributing editor John Fischer that proposed a comprehensive environmental college education, dubbed “Survival U.” In his article, Fischer referred to the U.S. Constitution as a “political artifact.” He quoted Professor Richard A. Falk of Princeton on the supposed “inadequacy of the sovereign states to manage the affairs of mankind in the twentieth century.” He explained that students at Survival U. would be encouraged to ask the following questions: “Are nation-states actually feasible, now that they have power to destroy each other in a single afternoon?... What price would most people be willing to pay for a more durable kind of human organization — more taxes, giving up national flags, perhaps the sacrifice of some of our hard-won liberties?

Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins bluntly stated on Earth Day 1970: “Humanity needs a world order. The fully sovereign nation is incapable of dealing with the poisoning of the environment.” He argued that “management of the planet … requires a world-government.” The same day, I. F. Stone, editor and publisher of I. F. Stone’s Bi-Weekly, opined in his own Earth Day speech, “There’s no use talking about Earth Day until we begin to think like Earthmen. Not as Americans and Russians … but as fellow travelers on a tiny planet in an infinite universe.” Both Cousins’ and Stone’s comments were included in Earth Day — The Beginning.

Earth Day Legacy

The original Earth Day was so successful in galvanizing the modern-day environmental movement that it is often credited with launching that movement. Soon after Earth Day 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established in the United States. But Earth Day has long since gone international, with last year’s Earth Day serving as the occasion for the signing of the draconian Paris climate agreement by many of the world’s countries, including the United States.

The agenda behind the original Earth Day remains unchanged today. Under a pretext of saving the planet, Earth Day alarmists and the environmental movement as a whole still advocate sacrificing our freedoms, our prosperity, and even our nation in favor of socialistic global governance. If the sinister aims behind the Earth Day “celebrations” were better, and more widely, understood, Earth Day’s popularity would likely fizzle.

Much of the information in this article also appeared in this writer’s March 26, 1990 article “The Greatest Sham on Earth.”

Photo: AP Images