Is the U.S. Intelligence Community Believable?

Can we trust the U.S. intelligence community when they say that Russia “hacked the election” to help Trump? Consider a past intelligence failure: Iraq’s alleged WMDs.

After thousands of e-mails from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) damaging to Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign were released by WikiLeaks in the weeks leading up to the 2016 election, Clinton attempted to divert attention away from the e-mails themselves. In the second presidential debate, she claimed “our intelligence community just came out and said in the last few days that the Kremlin, meaning Putin and the Russian government, are directing the attacks, the hacking on American [e-mail] accounts to influence our election.”

In the third and final debate, Clinton said that Russian President Vladimir Putin wanted “a puppet [Trump] as president of the United States.”

Indeed, as we reported in the February 20 edition of The New American, “In the weeks between Trump’s election and his inauguration, the intelligence community released two reports to the public claiming that the leaked DNC and Clinton e-mails and documents were the work of Russian state-sponsored hackers,” all designed to elect Trump.

“These are the same people that said Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction,” responded the Trump transition team to the report that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had concluded that Russia intervened in the presidential election to help Republican Donald Trump defeat Democrat opponent Hillary Clinton.

The Trump team’s response to such claims raises an important question: Can we trust the accuracy of reports from the CIA and other elements of the American intelligence community? To answer that question, it will be useful to look more closely at the events referred to above by the Trump team.

WMDs and Ties to Terror

Perhaps the best-known example of false information coming from the American intelligence community and an American presidential administration was the serial duplicity fed the American people and the Congress when they were told that Saddam Hussein was a threat to the United States because of his close ties to the al-Qaeda terror network and his supposed possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), such as biological, chemical, and even nuclear weapons.

The false claims led to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the loss of thousands of American lives and trillions of dollars of American treasure. It also led to the loss of many Iraqi noncombatants, including women and children, and an even more dangerous Middle East.

After the Persian Gulf War of 1991, the Iraqi government had agreed to destroy all of its WMDs and cease its WMD programs. It also agreed that inspectors from the United Nations would be allowed access to the country to verify that this was being done. This was accomplished over the next seven years, until UN inspectors left the country, saying that Iraq was no longer cooperating with them. President Bill Clinton then launched bombing strikes on targets inside Iraq in 1998, causing Iraq’s refusal to allow inspectors back in.

The atmosphere changed dramatically after the September 11, 2001 attacks upon the World Trade Center in New York City and on the Pentagon. Claiming fear that Iraq might be in league with Islamic terrorists, the George W. Bush administration threatened force, if necessary, to disarm Hussein of his reputed WMDs and remove him from power. The principal argument for this “regime change” was two-fold: Iraq had WMDs and was in league with al-Qaeda, the Islamic terrorist group behind the 9/11 attacks.

One cannot understand the willingness of the American people and the Congress to go to war against Iraq without both of these assertions. In fact, President Bush made this connection in October 2002, in very stark terms: “America must not ignore the threat gathering against us. Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof — the smoking gun — that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.”

In his January 28, 2003 State of the Union Address, President Bush was very specific in charging that Iraq still had large stockpiles of WMDs: “The United Nations concluded in 1999 that Saddam Hussein had biological weapons sufficient to produce over 25,000 liters of anthrax — enough doses to kill several million people. He hasn’t accounted for that material. He’s given no evidence that he has destroyed it. The United Nations concluded that Saddam Hussein had materials sufficient to produce more than 38,000 liters of botulinum toxin — enough to subject millions of people to death by respiratory failure. He hadn’t accounted for that material. He’s given no evidence that he has destroyed it. Our intelligence officials estimate that Saddam Hussein had the materials to produce as much as 500 tons of sarin, mustard and VX nerve agent. In such quantities, these chemical agents could also kill untold thousands. He’s not accounted for these materials. He has given no evidence that he has destroyed them.”

During the address, Bush raised the specter of the “mushroom cloud” — nuclear weapons — again, with backing from “intelligence.” Interestingly, however, this time he did not cite American intelligence agencies, but rather British intelligence. Speaking to a joint session of Congress, and a large television audience, Bush said, “The International Atomic Energy Agency confirmed in the 1990s that Saddam Hussein had an advanced nuclear weapons development program, had a design for a nuclear weapon and was working on five different methods of enriching uranium for a bomb.” Bush then uttered what have been called the “16 famous words,” in which he said Iraq could attack us not only with biological weapons such as anthrax, or chemical weapons such as mustard gas, but was actively pursuing the construction of atomic weapons: “The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” So “the British government” gave the Bush administration their intelligence about Saddam’s alleged nuclear-weapons program.

Bush buttressed this chilling prospect with, “Our intelligence sources tell us that he has attempted to purchase high-strength aluminum tubes suitable for nuclear weapons production.” And just in case any member of Congress or American watching the address on TV missed the point, Bush added, “Before September 11, many in the world believed that Saddam Hussein could be contained.... Imagine those 19 hijackers with other weapons and other plans — this time armed by Saddam Hussein.”

In a presentation to the UN Security Council on February 5, 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell echoed some of President Bush’s claims: “Our conservative estimate is that Iraq today has a stockpile of between 100 and 500 tons of chemical weapons agent. That is enough agent to fill 16,000 battlefield rockets.... Iraqi officials deny accusations of ties with al-Qaeda. These allegations are not credible.” How did Powell know this? He said his comments were not just “assertions,” but rather “facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.” In his presentation, Secretary Powell also agreed with President Bush’s statements on the Iraqi “nuclear weapons” program and their purchase of aluminum tubes: “Most U.S. experts think [the aluminum tubes] are intended to serve as rotors and centrifuges used to enrich uranium.”

Regarding Saddam Hussein’s ties to terrorism, Bush, in a February 6, 2003 radio address, said: “Iraq has sent bomb-making and document forgery experts to work with al-Qaeda. Iraq has also provided al-Qaeda with chemical and biological weapons training. And an al-Qaeda operative was sent to Iraq several times in the late 1990s for help in acquiring poisons and gases. We also know that Iraq is harboring a terrorist network headed by a senior al-Qaeda terrorist planner. This network runs a poison and explosive training camp in northeast Iraq, and many of its leaders are known to be in Baghdad.”

Then, in a February 8 radio address, Bush seemed to be sharing very specific intelligence when he said, “We have sources that tell us Saddam Hussein recently authorized Iraqi field commanders to use chemical weapons — the very weapons the dictator tells us he does not have.”

Clearly, Bush and Powell were assuring the American people that this troubling information came from intelligence, gathered by professionals inside the CIA and other such agencies.

During a March 6, 2003 press conference, Bush said, “Saddam Hussein and his weapons are a direct threat to this country, to our people, and to all free people.... I will not leave the American people at the mercy of the Iraqi dictator and his weapons.” “Intelligence gathered by this and other governments leaves no doubt that the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised.... The terrorist threat to America and the world will be diminished the moment that Saddam Hussein is disarmed,” Bush said in a March 17 address to the American public. And in a March 19 address to the nation on the eve of the war, Bush stated, “The people of the United States and our friends and allies will not live at the mercy of an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weapons of mass murder.”

On March 30, 2003 (10 days after the start of the Iraq War), Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said on ABC’s This Week With George Stephanopolous, “The area … that coalition forces control … happens not to be the area where weapons of mass destruction were dispersed. We know where they are. They’re in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat.”

Rumsfeld’s bold assertion was a continuation of the repeated claims made by the Bush administration and the American intelligence community before the war. In fact, Rumsfeld himself said before the invasion, “No terrorist state poses a greater or more immediate threat to the security of our people than the regime of Saddam Hussein and Iraq.”

This fear — that Hussein was working with al-Qaeda and could strike America with either a nuclear weapon, a biological weapon, or chemical weapons — caused most Americans to accept the necessity of invading Iraq and effecting regime change. Without this frightening prospect of Iraqi WMDs being used on America, most Americans would not have supported the 2003 invasion, and Congress would not have gone along.

The Reality: No WMDs

But after the invasion, which U.S. and coalition forces won rather quickly, Americans waited in vain for the capture of these supposed large stockpiles of WMDs. No evidence was ever found that Iraq was even working on a bomb. Iraqi Air Force General Georges Sada, an Assyrian Christian, wrote in his book Saddam’s Secrets that while Iraq had a nuclear-weapons project at one time, “it was destroyed in 1981” by an Israeli bombing raid and was never started back up again.

Lieutenant General James Conway, the commander of the First Marine Expeditionary Force, told reporters after the war, “It was a surprise to me then, it remains a surprise to me now, that we have not uncovered weapons … in some of the forward dispersal sites. Again, believe me, it’s not for lack of trying. We’ve been to virtually every ammunition supply point between the Kuwaiti border and Baghdad, but they’re simply not there.... We were simply wrong.”

When Reuters interviewed America’s chief weapons inspector, David Kay, on January 23, 2004, Kay was asked, “What happened to the stockpiles of biological and chemical weapons that everyone expected to be there?”

“I don’t think they existed,” Kay responded.

Eventually, Secretary Powell admitted he had been wrong about Iraq possessing WMDs, but said he believed they did — based upon what he thought was solid intelligence.

For the next year, coalition forces searched for the stockpiles of WMDs and programs. The search was led by the CIA and investigators from the U.S. Department of Defense. The failure to find WMDs — the alleged presence of which was the ostensible cause of the war — led to the creation of a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, chaired by Senator Pat Roberts (R-Kan.). The committee promised a “thorough and bipartisan review,” principally of two subjects: Iraq’s WMDs, and its alleged ties to terrorist groups.

The committee also said it would examine whether Hussein was a threat to “stability and security in the region,” and his “repression of his own people.”

Because of the insistence that Hussein possessed WMDs, and had ties to al-Qaeda, both of which turned out be wrong, the committee would look into “the objectivity, reasonableness, independence, and accuracy of the judgments reached by the intelligence community; whether those judgments were properly disseminated to policy makers in the Executive Branch and Congress; [and] whether any influence was brought to bear on anyone to shape their analysis to support policy objectives.”

Later, the committee expanded its probe to include other matters, including “the collection of intelligence on Iraq from the end of the Gulf War to the commencement of Operation Iraqi Freedom; whether public statements and reports and testimony regarding Iraq by U.S. Government officials made between the Gulf War period and the commencement of Operation Iraqi Freedom were substantiated by intelligence information; [and] the postwar finds about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and weapons programs and links to terrorism and how they compare with prewar assessments.”

The committee staff reviewed more than 30,000 pages of documentation provided by the intelligence community, but were denied copies of the President’s Daily Briefs (PDBs) that dealt with Iraq’s WMDs and its supposed ties to terrorists. But journalist Murray Waas has written that the PDB for September 21, 2001, only 10 days after the 9/11 attacks, said the U.S. intelligence community had found “no evidence” that Hussein had anything to do with the attack, and only “scant credible evidence” that he had any significant ties with al-Qaeda.

Much of the committee’s 511-page report focused on the October 2002 classified National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), entitled Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction. Its conclusions were very uncomplimentary: “Most of the major key judgments in the Intelligence Community’s October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction, either overstated, or were not supported by, the underlying intelligence gathering. A series of failures, particularly in analytic trade craft, led to the mischaracterization of the intelligence.”

In specific comments about the supposed domestic nuclear program, the committee concentrated on the intelligence work in early 2001, examining the attempts by Iraq to purchase 60,000 high-strength aluminum tubes. While the CIA had allegedly led Secretary Powell to believe these tubes were for the construction of centrifuges for a uranium-enrichment program, analysts for both the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense argued that was unlikely. In fact, the committee concluded that “much of the information provided or cleared by the Central Intelligence Agency for inclusion in Secretary Powell’s speech [to the UN] was overstated, misleading, or incorrect.”

Senator Roberts later told NBC’s Tim Russert that the U.S. government had used an alcoholic who was “utterly useless as a source” for their conclusion that Iraq had biological weapons. Roberts added that before the war, a Defense Department analyst contacted the CIA with his concern over this source, an Iraqi defector code-named “Curveball.” The CIA responded, “Let’s keep in mind the fact that this war’s going to happen regardless of what Curve Ball said or didn’t say. The Powers That Be probably aren’t terribly interested in whether Curve Ball knows what he’s talking about.”

How the Intelligence Failure Happened

In a bipartisan report, with Republicans in the majority on the committee, the senators concluded that no evidence existed that there were any WMDs, nor was there any complicity of Saddam Hussein in the 9/11 attacks. But, the committee said, after 9/11, “analysts were under tremendous pressure to make correct assessments, to avoid missing a credible threat, and to avoid an intelligence failure on the scale of 9/11.”

CIA Director George Tenet later lamented, when it became obvious that no such effort to obtain uranium from Africa had ever been attempted by Iraq, that Bush’s infamous “16 words” “should never have been included in the text written for the president.” But they were added, and Tenet took responsibility in a July 11, 2003 statement: “I am responsible for the approval process in my Agency,” Tenet said. He defended Bush in speaking those words, however, because “the President had every reason to believe that the text presented to him was sound.”

Later in his statement, Tenet made an effort to offer an explanation: “There was fragmentary intelligence gathered in late 2001 and early 2002 on the allegations of Saddam’s efforts to obtain additional raw uranium from Africa, beyond the 550 metric tons already in Iraq. In an effort to inquire about certain reports involving Niger, CIA’s counter-proliferation experts, on their own initiative, asked an individual with ties to the region to make a visit to see what he could learn. He reported back to us that one of the former Nigerian officials he met stated that he was unaware of any contract being signed between Niger and rogue states for the sale of uranium during his tenure in office. The same former official also said that in June 1999 a businessman approached him and insisted that the former official meet with an Iraqi delegation to discuss ‘expanding commercial relations’ between Iraq and Niger. The former official interpreted the overture as an attempt to discuss uranium sales. The former official also offered details regarding Niger’s processes for monitoring and transporting uranium that suggested it would be very unlikely that the material could be illicitly diverted.”

As a result of this report, Tenet believed it “did not resolve whether Iraq was or was not seeking uranium from abroad, it was given a normal and wide distribution, but we did not brief it to the President, Vice-President or other senior Administration officials. We also had to consider that the former Nigerian officials knew that what they were saying would reach the U.S. government and that this might have influenced what they said.”

So in the fall of 2002, Tenet did not include the uranium acquisition story in his briefings for “hundreds of members of Congress” on the situation in Iraq.

Then “our British colleagues told us they were planning to publish an unclassified dossier that mentioned reports of Iraqi attempts to obtain uranium in Africa. Because we viewed the reporting on such acquisition attempts to be inconclusive, we expressed reservations about its inclusion, but our [British] colleagues said they were confident in their reports.” (Emphasis added.)

Tenet said that senior intelligence officials told members of Congress that the CIA differed with the British on the “reliability” of the uranium reporting.

In fact, according to Tenet, the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research included a sentence that stated, “Finally, the claims of Iraqi pursuit of natural uranium in Africa are, in INR’s assessment, highly dubious.”

Because of this, nothing was said on the issue in many public speeches, congressional testimony, or the presentation of Secretary Powell. Yet, the 16 words still made it into the State of the Union message.

“Portions of the State of the Union speech draft came to the CIA for comment shortly before the speech was given,” Tenet said. “Various parts were shared with cognizant elements of the Agency for review.” Several “concerns” were raised about the 16 words. But, “Agency officials in the end concurred that the text in the speech was factually correct — i.e. that the British government report said that Iraq sought uranium from Africa.”

Tenet concluded, “This should not have been the test for clearing a Presidential address. This did not rise to the level of certainty which should be required for Presidential speeches, and [the] CIA should have ensured that it was removed.”

Changing the Story

In the face of mounting evidence that America had not gone to war out of concern that Saddam Hussein had links to al-Qaeda, possessed stockpiles of WMDs, and was even attempting to build atomic weapons, Secretary Powell admitted, “I don’t know,” to a question in 2004 from the Washington Post as to whether he would have recommended the invasion of Iraq. “I don’t know, because it was the stockpile that presented the final little piece that made it more of a real and present danger and threat to the region and to the world.”

This failure to find WMDs left the Bush administration scrambling for an explanation. One tactic used was to shift from the argument made before the war that Hussein had massive stockpiles of weapons to arguing that he had “programs” to produce such weapons. Bush even resorted to noting that American forces had discovered two “mobile” labs that he claimed could be used to “build biological weapons.” Note not that the Iraqis were building them, but they could.

Even this explanation proved to be a failure, however. Weapons inspector Kay concluded that no evidence existed that the two tractor-trailers had ever been used to produce biological weapons. “Technical limitations would prevent any of these processes from being ideally suited to these trailers.” It was finally concluded by the Defense Intelligence Agency that the two mysterious trailers were used to produce hydrogen for weather balloons.

When challenged, Bush lamely responded, “I mean, Iraq had a weapons program. Intelligence throughout the decade showed they had a weapons program.”

In an enlightening interview with ABC’s Diane Sawyer on December 16, 2003, Bush asked, “What’s the difference?” in response to Sawyer’s asking him about his prior insistence that Hussein already had WMDs, rather than that he could “move to acquire those weapons.” Bush added, “The possibility that he could acquire weapons. If he were to acquire weapons, he would be the danger.” (Emphasis added.)

“What’s the difference?” Put another way, would the American people have been persuaded to support going to war against Iraq if the administration’s pre-war claim was merely that Hussein “could acquire weapons”? But the administration said much more than that, and it did so to build support for launching an offensive war against a country that had not attacked us. In an amazing admission to Vanity Fair shortly after the war’s conclusion, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz said, “We settled on the one issue that everyone could agree on which was the weapons of mass destruction as the core reason.”

This moving target of why the Bush administration took the nation to war in 2003 raises an obvious question. If the question of WMDs in Iraq’s possession was, at best, only a secondary reason for going to war, and at worst, a subterfuge, then what was the real reason for going to war?

Empowering the UN

Perhaps an important clue lies in the statements of Bush’s father, who spoke glowingly of the 1991 Persian Gulf War as a building block for “New World Order.” Certainly, the United States could not be expected to achieve this grandiose scheme by itself. Even before the 2003 Iraq War, while President George W. Bush was expressing grave concerns about WMDs, he also made references to strengthening the United Nations.

“America will be making only one determination: is Iraq meeting the terms of the [UN] Security Council Resolution [1441, which ordered Hussein to disarm] or not?... If Iraq fails to comply, the United States and other nations will disarm Saddam Hussein.”

In an address to the UN General Assembly before the war, Bush said, “All the world now faces a test, and the United Nations a difficult and defining moment. Are Security Council resolutions to be honored and enforced, or cast aside?” Then, in a speech in South Dakota, Bush said, “I want the United Nations to be effective.... It makes sense for there to be an international body that has got the backbone and the capacity to help keep the peace.... The message to the world is that we want the UN to succeed.”

But Americans were told that we had to invade Iraq because of Iraq’s ties to terrorism and its stockpiles of WMDs, and that this was based upon “solid intelligence.” Americans were fed a steady diet of incomplete, inaccurate, and sometimes blatantly false information in the lead-up the war.

One could argue that this false information was incompetency, or one could argue that it was intentionally duplicitous. Certainly there is evidence supporting the latter, such as the administration pointing to British intelligence in the famous “16 words” in Bush’s 2003 State of the Union Address if U.S. intelligence did not draw the same conclusion, and also redefining the reputed WMDs as merely programs to make WMDs, as if there’s no difference between the two. But regardless if one concludes that it was incompetence or duplicity or some of both, it is uncontestable that the American president got the “findings” he wanted from the intelligence community and that these findings were false.

So when President Obama and a compliant intelligence community told us that the Russians “hacked” an American election in order to elect Trump over Clinton, the disturbing history of Iraq War intelligence justified a healthy dose of skepticism.

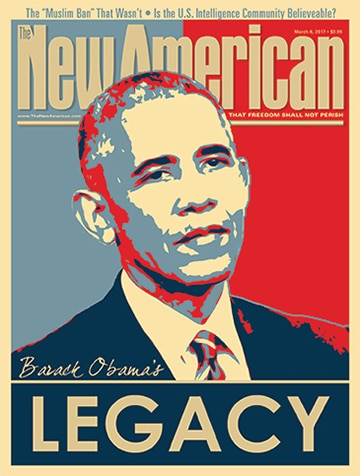

Photo: AP Images