How to Protect Our Environment

In 1990, the federal government put the northern spotted owl on the endangered species list. Then it proceeded to make virtually untouchable 24.5 million acres of federal land across three states: Washington, Oregon, and California.1 The stated idea was to preserve old growth forests where the owls — believed to number between 7,000 and 10,000 — could thrive. With many forests off-limits to logging, the timber industry went into a tailspin and tens of thousands of logging-related jobs were lost, yet the species has not been saved. The spotted owl is being killed off, and the culprit is — another owl, actually other owls. The barred owl, which desires similar food and habitat as the spotted owl, is more aggressive than the spotted owl and is pushing the spotted owl out of its territory, or killing it. Also, great horned owls are said to enjoy snacking on baby spotted owls.

The barred owl is native to the East Coast of the United States, but has moved west — presumably as a result of humans changing the landscape in the East. So, although it is illegal to kill a barred owl under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has given permission to a limited number of biologists to shoot barred owls, and is beginning a four-year experiment to kill thousands of the birds because the Fish and Wildlife Service is required under the Endangered Species Act to protect spotted owls. That is, the federal government is enforcing one federal law by ignoring another. If the spotted owls make a comeback in the areas where the barred owls are shot, more barred owls will be killed.2

If the barred owls are not controlled, some believe that they will literally drive the northern spotted owl extinct.

Quandaries of Conservation

When considering the best practices to preserve and even improve our country’s land, water, air, and animal populations, a juggling act of sorts often happens whereby environmental overseers (federal government functionaries) begin by taking in hand and juggling the competing interests of stakeholders: landowners, corporations, environmental groups, scientific groups, interested citizens, and local government. Then after a time, some groups’ wishes are kept aloft by the federal government, while others are dropped outright.

In the case of the spotted owl, initially it was the loggers’ and their families’ and communities’ cares that were let go, while the concerns of environmentalists were heeded. For many families who didn’t know what to do other than logging, life has been painful since logging was dramatically reduced. In 2006, a dozen years after the logging reduction, the New York Times reported about life in Oakridge, Oregon, in an article entitled “In Rural Oregon, These Are the Times That Try Working People’s Hopes.” Prior to forests being put essentially off-limits to logging, the paper said, “Into the 1980’s, people joked that poverty meant you didn’t have an RV or a boat. A high school degree was not necessary to earn a living through logging or mill work, with wages roughly equal to $20 or $30 an hour in today’s terms.” After most of the logging dried up, “Oakridge was wrenched through the rural version of deindustrialization … where much of any job growth has been in low-end retailing and services.” It was so bad, the Times wrote, “About 700 Oakridge residents, from a population of about 4,500 in Oakridge and the surrounding area, visit a charity food pantry each month to pick up boxes of groceries worth $100 apiece. Two-thirds of public school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, meaning their families are near the poverty line or below it. About 260 of the town’s 1,200 housing units are single-width trailers.” And each summer several families went under financially and moved into the forest, finding shelter as best they could.3

Because of the enforced poverty, some forest residents resorted to using illegal drugs or producing them and selling them, leading to a major increase in crime.4

Ironically, now that the barred owls are being shot, one group of environmentalists is challenging another. A group called Friends of Animals is suing the Fish and Wildlife Service to stop the shooting of barred owls. Its legal director, Michael Harris, told National Public Radio: “To go in and say we are going to kill thousands and thousands of barred owls, literally forever, I don’t see that as being a solution. At some point you have to allow these species to either figure out a way to coexist or for nature to run its course.”5

When considering the best possible remedy for protecting a piece of the environment in this country, in almost every instance, there are multiple stakeholders, and each usually claims that common sense or science backs its positions — often dubiously.

To decide who should protect the environment, we should first look to see who has protected it in the past and who best protects it now, as well as which group would allow Americans the most enjoyment of nature and their lives.

Those who consider themselves “environmentalists” — rather than conservationists, ecologists, or whatever other names there are for caretakers of the Earth — would likely, to a person, desire total government control over lands, waters, and air, whether national or international control.

And for proof that government is the answer to environmental problems, oddly enough, environmentalists would probably point to the northern spotted owl, despite its continued spiral toward its ultimate demise, because in the case of the owl, the government showed that it can and will allow the rejuvenation of “pristine” — human-free — wilderness, which is equally needed by other species, according to them. As a New York Times article entitled “Losing the Owl, Saving the Forest” pointed out and honest tree huggers have always admitted, the owl was merely a device by which to set aside “Northwest old-growth forest habitat”:

It was this irreplaceable ecosystem, centuries in the making, that environmentalists were really trying to protect under the terms of the act (whose first declared purpose is to conserve the ecosystems upon which endangered and threatened species depend); and the owl was their best available legal tool.6

The author, not really hiding the fact that he is an environmentalist himself, takes his jabs at those who lament the loss of logging:

I’ve met others … who say that the listing of the spotted owl is, unexpectedly, turning out to be a blessing, bringing more retirees to live there, more visiting hikers, hunters, surfers, birders and fly fishermen, and their money. The forest’s recovery is not without economic benefit to the people who live on its edges. For all that the timber communities have lost, there are signs that the hated environmentalists (“Are you an environmentalist? Or do you work for a living?” as the bumper stickers said) may have helped regenerate the very places they were once said to have ruined.6

Studies such as those covered in the report The Sky Did Not Fall: The Pacific Northwest’s Response to Logging Reductions are cited to show that environmentalists were/are correct about the innocuous effects of some drastic environmental restrictions. Though the authors of the report admit that “without doubt, some communities have had to cope with substantial, even wrenching, change,” they reasoned that the trauma was OK because “the PNW [the Pacific Northwest: Oregon and Washington] did not become an Appalachian-style region of entrenched poverty, as many had predicted.” In fact, they claim, “Instead, the region’s economy has persistently outperformed the rest of the nation in terms of growth in jobs and incomes,” with total employment in the area growing “27 percent.”7

But all that the authors really demonstrated was that logging jobs made up a relatively small percentage of all jobs in the Pacific Northwest prior to making federal forests basically off-limits to logging, not that it wasn’t a painful process. They still admit to a loss of some 24,104 jobs in the timber industry — though they (in the main) correctly claim many of these people would have lost their jobs eventually anyway because forest harvest levels were unsustainable.7

Overall, those who lost logging-related jobs and managed to find others made in wages only about 87 percent of what they did previously.7

I Should, We Should, They Should

Even if one concedes that setting aside millions of acres of federally controlled forests was an overall “good,” it cannot be justly claimed that the government did a good job of protecting the environment. The authors of The Sky Did Not Fall frankly admit government overseers did a poor job: “Federal District Judge William Dwyer shut down virtually the entire timber-sale program on nine national forests in Washington and Oregon until the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and other federal resource-management agencies could demonstrate that they had reversed ‘a remarkable series of violations of the environmental laws.’”7

By 1981, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service warned that the northern spotted owl might soon become endangered if the forests were not managed with the aim of protecting substantial areas of old growth forest. The authors note USFS’s response to the notice:

Despite this warning and those of numerous studies, strategies, and plans, Congress and federal land administrators did not develop and implement an effective conservation strategy. Instead, they stalled, unable or unwilling to accept the inevitable: that spotted owls would require marked reductions in timber harvests. They hoped that the problem would go away or that they could push the problem onto future Congresses, future administrators, and future generations. Indeed, rather than heed the 1981 warning from the Fish and Wildlife Service, the White House, and congressional leaders, forest managers more-than-doubled federal timber harvests by the middle of the 1980s.7

The USFS also did not manage the forests well from an economic perspective. The federal government lost millions of dollars because the price it was paid by loggers for the wood did not meet the government’s costs in remediating and reforesting the land.8, 9 As a result, old growth wood, which should have fetched a premium price and caused it to be processed in the United States, creating additional jobs, or left standing in the forests, was sold cheaply overseas, with taxpayers essentially picking up a large part of the tab. Authors Terry Anderson and Donald Leal explain the happenings in Free Market Environmentalism for the Next Generation: In the 1960s in the Bitterroot National Forest, “because the steep, cut-over slopes were not expected to regenerate naturally, the USFS bulldozed terraces in the hillsides to allow mechanized replanting and improve seedling regeneration,” and the projects cost “more than 35 times the value of the timber removed and forest amenity values were ignored.” Irresponsible forest management has proven true until recent times: “Between 1998 and 2001 the USFS lost $0.46 for every $1 spent on the timber program.”8

The authors of The Sky Did Not Fall noted, too, that government also charged the timber industry less in unemployment insurance payments than it paid out in unemployment claims, and it didn’t manage the logging in such a way so as to keep sediment from streams, costing water treatment centers and businesses money to remove the sediment and negatively affecting the reproduction of salmon, in turn hurting both the commercial and recreational salmon industries. (Additional proof that the government is not a good land steward can be found in the article "Causing the Natural Environment to Crumble" in the July 6 issue of TNA.)

A large part of the reason that government does a poor job of managing wildlife is that it is inflexible. For instance, following the preferred environmentalist methodology to protect and revive nature — providing human-free nature — the U.S. Forest Service in 1946 fenced off an area of abused land, and it remains off-limits, though it has become more and more barren over the years. The land did not recover. This land, the Drake Exposure in Arizona, had been protected from grazing and human activity for more than 68 years when Dan Dagget, who describes himself as an “EcoRadical” who became a “Conservative Environmentalist,” took pictures of the land and compared it to the land outside the enclosure, land used to graze cattle — cattle that were rotated off the property periodically to allow it to rejuvenate.

The land inside the enclosure was “as bare as a well-used parking lot,” as Dagget noted. And, according to him: “Studies show that 90% of the plant species that lived within its boundaries before it was protected no longer live there. In fact, much of the land supports no plants at all, and, judging from the lack of tracks and dung, not much wildlife either.”10

Outside the fence, “a healthy stand of native grasses has repopulated the land; the plant species that have ceased to exist within the Drake can still be found; and there is plenty of evidence of wildlife as well as livestock.” At his website — dagget.com — he compares pictures of various areas of land from before it was “protected” from grazing and human use to pictures taken afterward. The land was healthier when humans used it — and could hold more wildlife.10

Dagget, who was deemed in 1992 to be “one of the 100 top grass roots activists in the United States by the Sierra Club,” was one of the originators of the radical ecological group EarthFirst!, yet he now realizes that “victories” he had fought long and hard for, such as ending grazing on much public land, didn’t mend environmental problems.11 The erosion blamed on cattle grazing got worse, not better, as did the habitat as a whole and the carrying capacity of land. Now he is trying to show the world the damage caused by “protection.”

The government is inflexible for many reasons, but two predominate: Whichever lobbying group holds the most clout largely calls the political-environmental shots, and the government wrongly assumes that nature is by its nature unchanging.

Over many decades, as environmentalists got hold of the environmental political steering wheel, land managers, in an attempt to return land to its assumed optimal state, often took a hands-off approach when it came to wildlands (except to put out forest fires), under the assumption that nature would stabilize. But such a view forgets that early man and fires have had substantial impacts on the environment, and studies have demonstrated that even absent man environments in the past have constantly changed.

As was pointed out in Free Market Environmentalism for the Next Generation, when Yosemite Valley was made into a national park, its scenic beauty stood out because it had few trees and lots of meadows, owing to fires started by natives to clear land for crops. Since then the area has become dense forest. Likewise the area by Flagstaff, Arizona, in the Coconino National Forest formerly consisted of open forest with trees in clumps of 30 to 50 per acre, and the area was home to antelope. Today, “the trees are so dense there that a child can barely fit between them, yet a child’s hands can reach around the trunk of an 80-year-old tree.” “The wilderness of the Boundary Waters region … located on the Canadian border of Minnesota” is another example. “Using pollen records deposited in nearby lakes, scientists now know that since the end of the last ice age the forest passed from tundra to spruce to pine to birch and alder and then back to spruce and pine, changing composition every few thousand years.... These changes occurred even though, for much of that time, the area has largely been spared from the impact of humans.”8

Environmental laws of all stripes — from the Endangered Species Act to the Clean Water Act, the Wilderness Act, and more — are based on this inaccurate view of an ideal state of nature, where equilibrium can be found without human intervention, and they have led to endless environmental fallacies and problems.8

And because of such errant notions, the federal government’s land plans are largely “use it” or “not use it” schemes — mainly “not use it” plans, guided by eco-radicals — not “use it wisely” plans. In fact, when it comes to protecting the environment, “wisdom” is sorely lacking under federal control.

Where’s the Wisdom?

As a bit of proof of federal “lack of wisdom,” consider that the Environmental Protection Agency had until recently laws on the books to treat spilled milk using the same methodology as spilled crude oil because of the fat in the milk.12 There’s more:

• Because of federal regulations protecting a non-endangered bird, the double-crested cormorant, the city of San Francisco expects to pay in excess of $33 million to capture and move 800 birds — instead of driving them away through construction activity — as the city slowly demolishes an old section of the Bay Bridge. The city contends that it’s cheaper to capture the birds than to face fines by the government. The birds have ample places to rest and nest on the new bridge, which is only yards away.13

• When the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded in 2010, causing the worst oil spill in U.S. history, North Atlantic countries offered their oil-skimming equipment to greatly ameliorate the environmental damage from the spill, but the U.S. government said “no” because it would go against the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, which requires all ships transporting goods between U.S. ports to be U.S.-owned ships — to protect labor unions from competition. This act was only waived after two months.14

• The EPA is making plans to lower the amount of allowable ground-level ozone (smog) — caused by the chemical reaction between gaseous emissions and heat from sunlight — to levels so low that even non-industrialized areas of the country, such as Yellowstone National Park, Death Valley National Park, and Sequoia National Park, wouldn’t meet the standards, an action that would decimate U.S. manufacturing.15, 16

In addition to being inflexible and shortsighted, the federal government does everything in its power to accumulate more power in government, which for individual liberty’s sake — and individual happiness — should be fought at all costs. One of the most notable examples of this is the government’s effort to control carbon dioxide.

Under a regime that would control how much carbon dioxide is emitted, the government intends to influence virtually every human activity — meaning it intends to limit virtually every activity. Right now, the Obama administration is attempting to force adherence to UN goals on CO2 emissions via executive fiat,17 UN goals that top UN climate chief Christiana Figueres told The Guardian newspaper in 2012 will result in a “centralized transformation” of humanity and the planet, “one that is going to make the life of everyone on the planet very different.”18

Yet anyone who understands both something of the climate debate and the scientific method, wherein once a hypothesis is forwarded it must survive tests to prove its validity, should immediately recognize that the global-warming hypothesis fails scrutiny — incredibly fails!

In the world of global warming, even as those who predict climate doom claim to see catastrophic warming with their own eyes in the form of melting ice and warmer-seeming temperatures, it must be acknowledged that dire predictions of climate doom are in actuality predicated on 97 computer models that prophesy death-dealing temperatures, owing to increased human-released carbon dioxide. Yet logic should tell us not to believe the models.19

• First, climate-alarmist websites state that CO2 levels rose fairly steadily for the past 8,000 years (and claim levels have jumped dramatically in the past 500 years, owing to man),20 yet Earth has also generally cooled over that time — with a few relatively brief, slight upticks in temperature resulting in melting glaciers, such as the Roman and Medieval warm periods, 2,350 and 1,400 years ago, respectively.21, 22

• Second, every single one of the 97 computer models predicted continual significant warming of the Earth, which hasn’t happened — the global mean temperatures have stayed steady for at least the past 18 years, according to satellite readings (most land-based readings suffer from the urban heat effect, biasing them; those that aren’t biased show slight cooling happening).21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

• Third, the Earth has been warming in fits and starts since the early 1800s, and the warming that we’ve seen since the 1980s mirrors the trends from that time — the rate of warming is unchanged despite CO2 increasing by 38 percent in the atmosphere since the 1800s.24, 29, 30 And from the 1940s to 1975, despite CO2 levels climbing rapidly, temperatures dropped, with scientists predicting another ice age.31, 32

• Fourth, temperature records as gleaned from coral, ice cores, harvest dates, ice breakup dates, tree rings, and tree blossoming dates from Japan and China, all show that temperatures are just now nearing their 3,000-year average, despite the Earth having gone through a mini-ice age during that time, meaning that in the past 3,000 years, it was much warmer than it is now — naturally — and that the temperatures in our times are still very much within normal temperature fluctuations on Earth.31 Oh yeah, all the plants and animals that people are worried about losing to increased heat lived through that period just fine. As well, as was indicated earlier, the Earth’s temperature is now significantly cooler than the Earth’s 8,000-year average.22, 25

• Fifth, though CO2 is indeed a greenhouse gas and does trap some of the Sun’s heat, satellite readings show that it acts like a blanket or blankets on the human body: Adding more and more layers only provides a limited amount of additional warming. Carbon dioxide does not cause heat to be trapped to the extent that it would cause catastrophic global warming.33, 34, 35

• Sixth, multiple ice core studies, with records going back hundreds of thousands of years, indicate that temperature increases on Earth in the past happened immediately before the amounts of CO2 in the air increased, not the other way around — probably because of out-gassing of CO2 from the oceans as temperatures increased.36

There’s more, but this should be enough information to dispel any confidence in predictions generated by computer models of warming based on CO2 levels. To be blunt, there’s no historical or scientific proof that CO2 drives climate change — it’s all speculative theory — while there is substantial proof that climate change can drive CO2 levels. Claims of man-caused catastrophic warming based on CO2 cannot be called credible if one adheres to the scientific method.

Many Americans choose to believe, however, that the Obama administration and the UN are just doing what they need to do to save the planet, but it’s been clear for years that talk about the “environment” is really talk about “control.” The UN’s environmental goals have been unchanged since they were spelled out in the Agenda 21 document at the 1992 UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. That document lays out — as Daniel Sitarz, who edited the document, said — “an array of actions which are intended to be implemented by every person on earth,” a plan that “will require a profound reorientation of all human society, unlike anything the world has ever experienced.”37 And in February, Christiana Figueres once again reiterated the fact that the UN’s plan would lead to a total restructuring of the world’s economies: “This is the first time in the history of mankind that we are setting ourselves the task of intentionally, within a defined period of time to change the economic development model that has been reigning for at least 150 years, since the industrial revolution.”38 Considering that during the last 150 years, free market capitalism has played the predominant role in economic dealings, her words can only mean that the UN has plans to implement centralized control of countries’ economies.

For those who might be cheering Figueres in their hearts, it pays to honestly recall the poor results totalitarian governments have achieved in providing individual freedom, wealth, and happiness — and a pristine environment. The article “An Environment Without Property Rights” gives a little perspective on the direction total government control over nature tends to take:

When Eastern Europe began to open up in the late 1980s, one of the great shocks was the severity of its environmental problems. Journalists reported on skies full of smoke from lignite and soft coal, children kept inside for much of the winter because of unsafe air, and horses that had to be moved away from the worst areas after a few years or they would die.

… Old, polluting factories of the kinds that are dim memories in the United States were the mainstay of socialist industry. Smelly, sluggish automobiles polluted the roads.

Energy waste was tremendous. Their own statistics showed that socialist economies were using more than three times as much steel and nearly three times as much energy per unit of output than market economies.39

When the Iron Curtain parted, Poland was one of the world’s most polluted countries.40

Even now, a brief perusal of the Internet or a conversation with someone who has toured China will convince all but the most skeptical that the communist government controlling China is literally destroying that country’s environment, and the problems are so systemic that China regularly exports polluted foods worldwide.41, 42, 43

And centralized control is a worldwide problem. For instance, the main countries where rainforests are being chopped down — Brazil, Madagascar, Peru, Colombia, Central African Republic, etc. — have highly authoritarian governments.

This damage done to the environment by governments is known as the “tragedy of the commons”: When it’s deemed that the public owns nature, nobody’s really responsible for caring for nature, and tragedy results.

Government Glomming

Governments, whether federal or international, always want to amass more power — playing God over individuals and nature alike, to the detriment of both. And as the U.S. government assumes power unto itself, its ability to effect positive environmental change generally declines. Yes, declines. Because of the enormity of the task of managing the country’s environment, federal politicians and bureaucrats increasingly make what are essentially uninformed snap decisions about what to do with the environment (usually decisions about using or not using certain lands), decisions not based upon science, but upon lobbying, kickbacks, and politics.

Take for instance what should be done to protect the sage grouse from extinction, the population of which in the last 100 years is estimated to have fallen from 16 million to less than a half million. As far as the federal government is concerned, it’s a political decision. The EPA made an agreement with environmental groups to either list the grouse as “endangered” by 2015 or take it off the list of “threatened” animals. Because of political pressures, the agreement to “list” or “delist” the grouse is being postponed for now — likely until September. Listing the grouse would cause millions of acres of land to become off-limits in areas where the country is experiencing a fracking energy boom, providing the main job gains in the economy.44, 45 Now, undoubtedly owing to the fact that Republicans gave Democrats a thorough drubbing in the 2014 elections and Democrats are avoiding a repeat in 2016, the federal government has released a land-use plan to stop the grouse from getting an ESA listing, which, though restrictive on landowners, is less onerous than would occur under an ESA listing.

When deemed expedient, politics will trump protection every time.

And even if it weren’t for political expediency, the federal government would not likely make wise choices about care for the sage grouse or the environment. In fact, it likely couldn’t.

In the case of the sage grouse, to make an informed decision about instituting measures to aid it, one not only has to know what is causing the population to decrease — which is speculative right now and varies from fragmentation of habitat, to invasion by non-native species, to increased wildfires, to the prevalence of West Nile virus, to a lack of nesting cover, to the type and quality of nutrition that the chicks are receiving, and more — one has to determine what changes will bring about more grouse recruitment.46, 47

And what must be done to protect the sage grouse differs depending on location, season, altitude, precipitation, plant species, grazing, the number and types of wildlife, the soil type, the incline of the terrain, etc.

Take just wildfires for a moment. Not only do the frequency and timing of wildfires affect sage grouse numbers, but wildfire severity makes a difference. And the number and severity of wildfires in sage country are influenced by the existence and amounts of more than a dozen types of plant species — plant species that can spread or wither based upon cattle grazing at certain times of the year, in certain areas. Note that cattle and sheep are about the only things besides mechanical and chemical processes that can be used to control various plant species. Fire conditions can be made worse or better depending upon not only when cattle are grazed but upon the type of weather the country is experiencing. For instance, cattle can be used to get rid of cheatgrass, an invasive species that promotes frequent wildfires, if the cattle are used as bovine lawnmowers in early spring and when the grasses are dormant in winter, but grazing can actually increase cheatgrass amounts if done when there is a moist fall and early season rains.48

Likely no person anywhere could know how to protect the sage grouse across all of its habitat because of varied and changing conditions. As well, under the endangered species act, the federal government would likely actually hinder aid for the grouse: It would make grouse habitat largely off limits, basically ensuring that few, if any, cattle or sheep will be allowed to control plant proliferation for the birds’ benefit.

Just locking up the land won’t work to save most native species! Of the 30 species that have been delisted from protection under the Endangered Species Act, it’s not evident from a cursory perusal of them that any were mainly saved by ESA land set-asides (especially the three species of kangaroos that somehow made the list, though they aren’t native to this continent). And of many of the other species “saved” by the act, it’s clear that if the act had any role in the animals’ resurgence, it was a small one since the animals were already coming back owing to other reasons: the gray whale (an international agreement to stop hunting them was passed in 1946),49 the alligator (alligators, too, were already protected), the bald eagle (it was always very common in Canada and Alaska), and more.50 Though it’s very likely that in some cases land set-asides could be very beneficial to certain wildlife populations, there is little evidence that its widespread application is justified.51 In fact, without human intervention, invasive species will run their course and wipe out many less-competitive native species (as has already happened throughout almost the entire Hawaiian landmass),52 and so the environment on this continent can never return to the state it was before European influence, even if man were to disappear from the Earth overnight. Local knowledge must be applied — local knowledge that federal regulations undercut and bypass.

It’s interesting that the majority of the land on which the sage grouse live is under the control of the federal government already,45 and has been for many, many years — just as is true in the case of the northern spotted owl.

In truth, the ESA will likely be the cause of death of many species because of its inane backward incentives: Landowners know that their property can be made off-limits to them if an endangered species is found on it, so they have every financial reason to make their land inhospitable to endangered species. As well, endangered species inhabit some private lands precisely because the owners’ land practices made the area desirable in the first place, and changes to the land practices can inadvertently make the land undesirable. Iain Murray noted in The Really Inconvenient Truths: Seven Environmental Catastrophes Liberals Don’t Want You to Know About — Because They Helped Cause Them one case:50

In 1990, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had ordered the Domenigonis to stop cultivating all eight hundred of their tillable acres, stating this would constitute a “taking” of the [kangaroo] rat. For which they would face impoundment of their farm equipment, a year in jail, and possibly a $50,000 fine for each and every taking of an individual rat. For three seasons their fields lay idle and they lost $84,000 in foregone crops each season. The land friendly practices they had developed over a century were stopped.

They were only allowed to farm again after 1993 when, after a fire, it was determined that the rats had already left the property “because the brush and weeds had grown too thick for them.”

In the end, the case for federal or international control over the environment comes down to power — the power to get things done. But much of the case against federal or international control of the environment also comes down to power — the abuse, misuse, and misapplication of power.

People often assume that government must protect the environment because citizens don’t have the wherewithal to sue big businesses that pollute, but if they think suing businesses is difficult, they should try suing the government when it’s in the wrong. A U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service website brags, “In over twenty years (since the enactment of the Endangered Species Act) not a single case seeking compensation for illegal seizure of private property under the Endangered Species Act has come to the U.S. Court of Claims.”53 (Actually, as of 2013, the Congressional Research Service had found one case where the government was found in the wrong.)54 Similar boasts appear at various government websites, and they are meant to reassure web readers that the government has almost no negative effect on private landowners’ land and water rights. But nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, the government almost never gets penalized for “taking” people’s property because the government has defined “taking” in such a way that court cases are nearly unwinnable. The government hurts property owners such as the Domenigonis noted above almost constantly, but it is virtually impossible to get justice, or even remuneration.54

Localized Land Control

While no system will stop all environmental destruction, to aid the planet, we need to look to local solutions for the best results, which have the side benefit of adding the least infringements on people’s freedoms.

The success stories of private citizens and entities in sustaining the environment and wildlife populations are legion. Members of Ducks Unlimited and hunters get the main credit for reviving wood duck populations by building and promoting human-built duck boxes to promote procreation. In Colorado alone the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation has enhanced hundreds of thousands of acres of habitat for elk and mule deer, including planting aspen and conducting prescribed burns. Pheasants Forever, whose chapters “retain 100 percent decision-making control over their locally-raised funds” and allow “chapter volunteers to develop wildlife habitat projects and conduct youth conservation events in their communities,” is the leading advocate of pheasants and quail and their habitat. Then there are also similar accomplishments by Whitetails Unlimited, the National Wild Turkey Federation, Trout Unlimited, etc.

And environmental groups are finding creative new ways to use free markets to meet their environmental goals. The Montana Land Reliance raises funds to purchase permanent easements on private land. It has more than 800,000 acres under easement. The National Audubon Society — usually considered a very left-wing outfit — leases out its lands in the Intracoastal Waterway in Louisiana for energy development, in order to raise money for land stewardship.8 (Ironically, it fights against the same type of arrangements on public lands.) And there are many more examples, many of which can be found in Free Market Environmentalism for the Next Generation.

Though private groups have accomplished a lot of their environmental successes by poking, prodding, and otherwise influencing government policies, there can be no doubt that these private groups spearhead saving wildlife and habitat, often providing both the knowledge base and the manpower to effect progress.

As to the problems of citizens not being able to sue big companies or effect changes to air and water across state lines, while there is some truth to the claim that the private environmental umbrella has holes, it should also be acknowledged that most of the reason that private parties are not able to protect the environment now is because government has stood in their way — taking away the tools they need to do the job (such as by extinguishing property rights)!

Interestingly, one of the tragedies that environmentalists commonly point to as the impetus behind, and the need for, the EPA and environmental laws is the burning of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland in 1969. The river was so polluted that the oil and debris in the river caught fire (an occurrence that was fairly common in early industrial cities). Environmentalists blamed, and still blame, big business for stomping out local efforts to save the river, which turns out to be largely false. As Iain Murray explained:

In early American history, th[e] principle of private ownership supported by common law was the model for waterways … [but] this principle changed, with the “progressive” notion of common ownership replacing it. With water belonging not to individuals, but to the state, the way was open for pollution....

This meant that industrial areas tended to treat their commonly owned rivers as common dumping grounds.50

Since most people in Cleveland considered industrialization to be a good thing, the situation grew worse, with numerous fires on the river. But when citizens and businesses reached a level of affluence where they could afford to care and they finally objected to the pollution, first the local government protected the polluters; then the state government did the same.

Murray elaborated:

After the Cuyahoga had spent decades as an “open sewer,” a paper manufacturer sued the municipality in 1936 to prevent the city dumping sewage into the river, harming the manufacturer’s business. The city, on the other hand, claimed it had a “prescriptive right” to use the river in that way.

Influenced by decades of “progressive” thought, the court agreed with the city — the city government got to determine what was done with the river, no matter how much it harmed others.

In the 1940s, the tides began to turn against localities’ “prescriptive rights,” and, Murray notes, cities and businesses were likely to soon find themselves the defendants in losing pollution lawsuits — until the state took over the role of polluter-in-chief.

By 1952, Cleveland residents expected better for their environment, valuing the river for its own sake, and they began a river cleanup. “In 1959, fish reappeared, testimony to some remarkable progress.” But in the 1960s, the state took over management of the river and began issuing permits to dump pollutants into the river. And, again, courts found for the polluter:

In 1965, for example, a real estate company sued the city to stop allowing use of the river as an industrial dump. It won, but the verdict was overturned by the state supreme court, which found that state law trumps common law rights.

On the other hand, where the law is designed to allow private individuals or groups to manage and protect nature, it does work.

Private Property Is the Answer

Remembering that all disputes over the environment are really arguments over differing plans for how to use the country’s resources, it makes sense that competing interests put their money where their beliefs are and essentially bid in the open market for their desired outcomes. The alternative is the present system where the government makes decisions, and there is no give-and-take between the disagreeing parties. There is simply total victory for one side or the other, the side that can best afford to lobby Congress — with some concessions made via litigation. It’s a methodology hardly likely to lead to wise policy.

By strengthening property rights, even seemingly intractable problems could be resolved through the private sector. In the West, historically, rights to free-flowing water went to the first people to use the water; they took what they needed, and what they didn’t use, someone else could claim and use. Increased numbers of users meant that water supplies couldn’t satisfy all demands: for agriculture, fish, and home use. In states where property rights to water were later defined, secured, and made transferable, consumers then set a value on, bought, and sold water rights, and lo and behold stream levels increased to the point of supporting fish such as trout. Similarly, using revamped property rights, falling groundwater levels in the Tehachapi Basin in California were halted and reversed. And ocean fish stocks that had been overfished for decades have rebounded.8

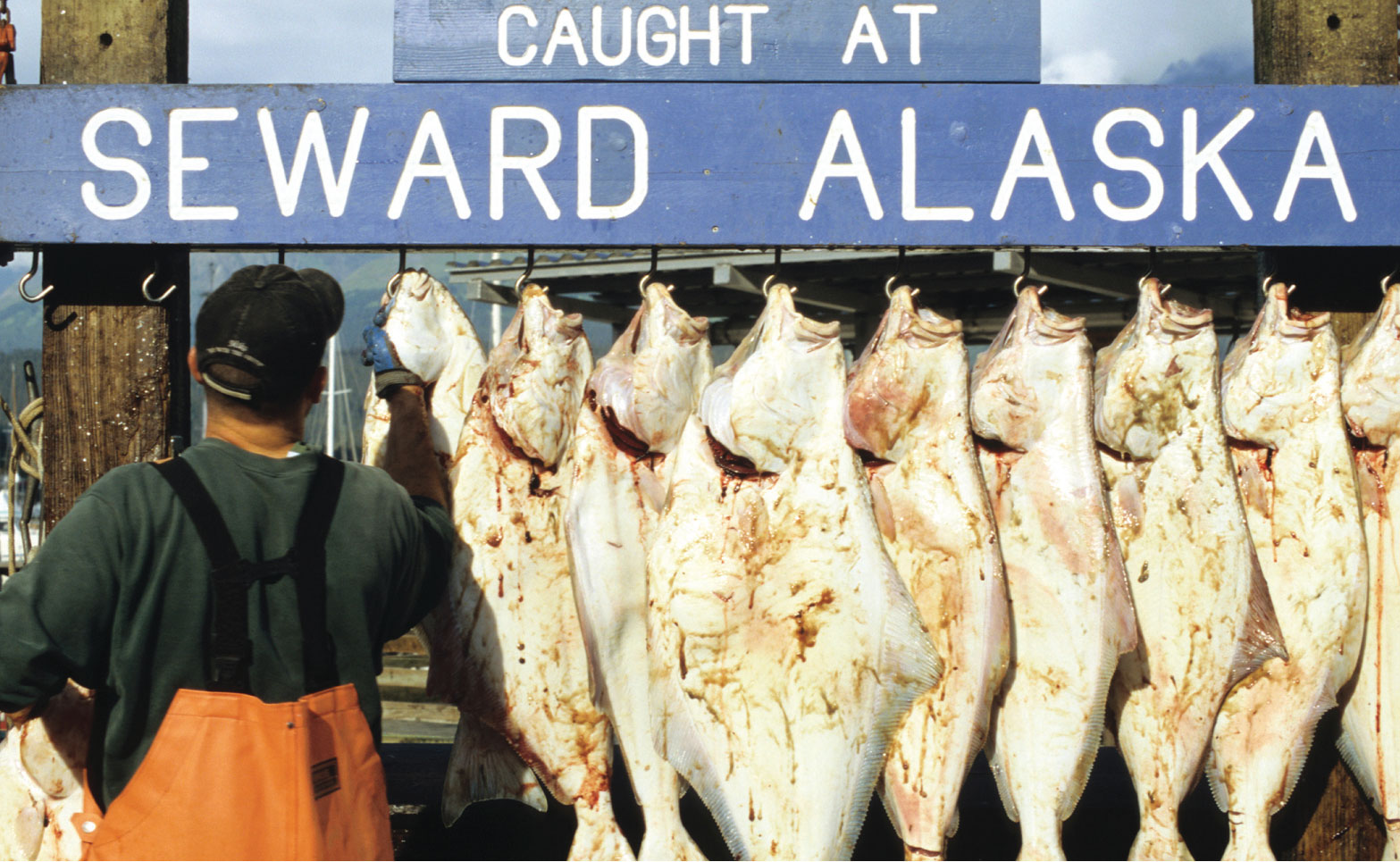

Take, for instance, halibut populations in Alaska. As consumers became enamored of the white, flaky fish, boats got bigger, hook design better, and technique more sophisticated. And the halibut population became depleted. The government, in turn, reduced fish catch totals and fishing seasons drastically. Fishing seasons declined from several months to three days. The result: bycatch (untargeted fish that happened to get caught, which is thrown back, usually dead) went up substantially, millions of pounds of halibut weren’t properly stored and spoiled, and boats’ fishing lines became tangled and lost, leading to tens of thousands of hooks catching fish on abandoned lines. The fishermen then brought 10 million pounds of halibut to the dock all at once, depressing fish prices and leading to the fish being sold frozen, rather than fresh.8

When property rights were tried in the halibut fishery, termed “individual fishing quotas” or “catch shares,” wherein fishermen are able to purchase shares of the allowable fish quota (and also sell unused shares), bycatch went down dramatically, less fish spoiled, more fish were sold fresh, fewer lines were lost, and the fishery began to recover.8

With continental shelves providing up to 90 percent of fisheries’ production,55 property rights for fish can protect most of the world’s fish stocks, and are, in fact, already being implemented by many countries successfully. A positive side effect of defining and protecting property rights in the marine environment is that it encourages fishermen to care for fish stocks, instead of racing to get as many fish as they can — before someone else can catch them.

Environmentalists often claim that private ownership of land and water, combined with greed, leads to environmental devastation (which is often the truth in poor countries, until most citizens in a country leave poverty), but history shows most property owners try to keep their properties as valuable as possible in order to benefit from its use or its future sale — falsifying the environmentalist claim.

On the whole, at this point in time, free markets might not be the panacea to fix all environmental problems. But that is mainly because the legal foundation has not yet been developed to allow private parties to monitor and protect the environment, and the beings in it. However, if free market environmentalism is encouraged to develop by smart laws, free markets would likely quickly find the answers for most regulatory problems.

And the alternative has no chance of working anyway, so let’s dive in.

Bibliography

1. “Northern Spotted Owl Conservation in Washington State.” Washington Forest Protection. Accessed online January 2015. Online @ http://www.northernspottedowl.org/jurisdictions/nwfp.html

2. Groc, Isabelle. “Shooting Owls to Save Other Owls. National Geographic. July 19, 2014. Online @ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/07/140717-spotted-owls-barred-shooting-logging-endangered-species-science/

3. Eckholm, Erik. “In Rural Oregon, These Are the Times That Try Working People's Hopes.” New York Times. August 20, 2006. Online @ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9804E2D7153EF933A1575BC0A9609C8B63

4. Loomis, Erik and Ryan Edgington. “Lives under the canopy: Spotted owls and loggers in Western Forests.” Natural Resources Journal, volume 52. Spring 2012. Online @ http://lawschool.unm.edu/nrj/volumes/52/1/loomis_edgington.pdf

5. Shogren, Elizabeth. “To save threatened owl, another species is shot.” npr. January 16, 2014. Online @ http://www.npr.org/2014/01/15/262735123/to-save-threatened-owl-another-species-is-shot

6. Raban, Jonathon. “Losing the Owl, Saving the Forest.” New York Times. June 26, 2010. Online @ http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/27/opinion/27raban.html?_r=0

7. Niemi, Ernie et al. The Sky Did Not Fall: The Pacific Northwest’s Response to Logging Reductions. ECONorthwest. April 1999. Online @ http://pages.uoregon.edu/whitelaw/432/articles/SkyDidNotFallFull.pdf

8. Anderson, Terry L. and Donald R. Leal. Free Market Environmentalism for the Next Generation. Palgrave Macmillan: 2015

9. Cole, Daniel H. “Clearing the Air: Four Propositions About Property Rights and Environmental Protection.” Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum, volume 10:103. Fall 1999. Online @ http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1514&context=facpub

10. Dagget, Dan. “Another Liberal Failure: Unmasked on the Arizona Range.” Dandagget.com. June 5, 2013. Online @ http://www.dandagget.com/

11. Dagget, Dan. “From EcoRadical to Conservative Environmentalist.” Dandagget.com. March 29, 2013. Online @ http://www.dandagget.com/

12. “Gibbs: Eliminate EPA’s Designation of Milk as an Oil.” Ohio Free Press. November 11, 2011. Online @ http://www.ohiofreepress.com/2011/gibbs-eliminate-epa%E2%80%99s-designation-of-milk-as-an-oil/

13. Cowan, Claudia. “$40G per bird? California cormorants refuse to budge from bridge being demolished.” Foxnews.com. November 10, 2014. Online @ http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/11/10/40g-per-bird-relocating-protected-cormorants-to-raze-bridge-breaks-bank/?cmpid=cmty_twitter_fn

14. Green, Craig. “Free Market Environmentalism: Private Sector Better at Preservation.” Property and Environment Research Center. Accessed online January 2015. Online @ http://www.perc.org/articles/free-market-environmentalism-private-sector-better-preservation

15. Newman, Alex. “Obama Imposed 75,000 pages of New Regulations in 2014.” TheNewAmerican.com. December 30, 2014. Online @ http://www.thenewamerican.com/usnews/constitution/item/19803-obama-imposed-75-000-pages-of-new-regulations-in-2014

16. Batkins, Sam and Catrina Rorke. “100 National and State Parks Could Fail to Comply With EPA’s New Ozone Regulations.” American Action Forum. December 8, 2014. Online @ http://americanactionforum.org/insights/100-national-and-state-parks-could-fail-to-comply-with-epas-new-ozone-regul

17. Newman, Alex. “White House Unveils $100B ‘Climate’ Schemes, Mocks Congress.” TheNewAmerican.com. November 18, 2014. Online @ http://www.thenewamerican.com/tech/environment/item/19558-white-house-unveils-100b-climate-schemes-mocks-congress

18. Kolbert, Elizabeth. “Global Warming Talks Progress Is ‘Slow but Steady’ — UN Climate Chief.” The Guardian. November 21, 2012. Online @ http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/nov/21/global-warming-talks-progress-un-climate-chief

19. Larabell, John. “The Rise of Doublethink.” The New American. January 5, 2015

20. “How Reliable Are CO2 Measurements?” skepticalscience.com. Accessed May 1, 2015. Online @ http://www.skepticalscience.com/print.php?r=58

21. Hiserodt, Ed and Rebecca Terrell. “Is Global Warming a Hoax?” The New American. January 5, 2015. Online @ http://www.thenewamerican.com/tech/environment/item/19840-is-global-warming-a-hoax

22. “Holocene Climatic Optimum.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 8, 2015. Online A http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocene_climatic_optimum

23. Monckton, Christopher. “It’s official: No Global Warming for 18 Years 1 Month.” Watts Up With That? The World’s Most Viewed Site on Global Warming and Climate Change. October 2, 2014. Online @ http://wattsupwiththat.com/2014/10/02/its-official-no-global-warming-for-18-years-1-month/

24. Jasper, William F. “Computer Models vs. Climate Reality.” The New American. April 20, 2015. Online @ http://www.thenewamerican.com/tech/environment/item/20610-computer-models-vs-climate-reality

25. Watts, Anthony. “Is the U.S. Surface Temperature Record Reliable?” March 1, 2009. SurfaceStations.org. Online @ https://www.heartland.org/sites/default/files/SurfaceStations.pdf

26. “Climate Monitoring: NOAA Can Improve Management of the U.S. Historical Climatology Network.” United States Government Accountability Office. August 2011. Online @ http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d11800.pdf

27. “National Temperature Index.” National Climatic Data Center. Accessed May 8, 2015. Online @ http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/national-temperature-index/

28. “Scientists Debunk Climate Models.” The New American. April 20, 2015. Online @ http://www.thenewamerican.com/tech/environment/item/20630-scientists-debunk-climate-models

29. Sharp, Jonathon H. “Increasing Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.” College of Marine & Earth Studies University of Delaware. February 13, 2007. Online @ http://co2.cms.udel.edu/Increasing_Atmospheric_CO2.htm

30. “Scripps Mauna Loa CO2 Data Summary (Monthly and Annual).” CO2Now.org. June 4, 2015. Online @ http://co2now.org/current-co2/co2-now/

31. Akasofu, Syun-Ichi. “The Recovery from the Little Ice Age (A Possible Cause of Global Warming) and the Recent Halting of the Warming (The Multi-decadal Oscillation).” January 23, 2008. Online @ http://people.iarc.uaf.edu/~sakasofu/pdf/two_natural_components_recent_climate_change.pdf

32. The Great Global Warming Swindle. March 8, 2007. Online @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52Mx0_8YEtg

33. Taylor, James. “New NASA Data Blow Gaping Hole in Global Warming Alarmism.” Forbes. July 27, 2011. Online @ http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamestaylor/2011/07/27/new-nasa-data-blow-gaping-hold-in-global-warming-alarmism/

34. Spencer, Roy W. “Satellite and Climate Model Evidence Against Substantial Manmade Climate Change.” December 29, 2008. Online @ http://www.drroyspencer.com/research-articles/satellite-and-climate-model-evidence/

35. Spencer, Roy W. and William D. Braswell. “On the Misdiagnosis of Surface Temperature Feedbacks from Variations in Earth’s Radiant Energy Balance.” Remote Sensing. July 25, 2011. Online @ http://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/3/8/1603

36. Ferguson, William. “Ice Core Data Help Solve a Global Warming Mystery.” Scientific American. March 1, 2013. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ice-core-data-help-solve/

37. Coffman, Michael S. “Globalized Grizzlies” The New American. August 18, 1997. Online @ http://fpparchive.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Globalized-Grizzlies_Michael-S.-Coffman_August-18-1997_The-New-American.pdf

38. “Figueres: First time the world economy is transformed intentionally.” United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe. February 3, 2015. Online @ http://www.unric.org/en/latest-un-buzz/29623-figueres-first-time-the-world-economy-is-transformed-intentionally

39. Stroup, Richard L. and Jane S. Shaw. “An Environment Without Property Rights.” Independent Institute. February 1, 1997. Online @ http://www.independent.org/publications/article.asp?id=196

40. Cole, Daniel H. “Clearing the Air: Four Propositions about property rights and environmental protection.” Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum. 1999. Online @ http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1169&context=delpf

41. Sedghi, Sarah. “Frozen berries hepatitis A scare: Pollution poses challenges to Chinese food safety practices.” ABC News (Australia). February 20, 2015. Online @ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-02-20/pollution-poses-challenges-to-chinese-food-safety-practices/6164494

42. Huehnergarth, Nancy. “China’s food safety Issues Worse than you thought.” Food Safety News. July 11, 2014. Online @ http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2014/07/chinas-food-safety-issues-are-worse-than-you-thought/#.VWSK84eLlrc

43. Zamiska, Nicholas. “Who’s Monitoring Chinese Food Exports?” Wall Street Journal. Online @ http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117608207682763704

44. Flatt, Courtney. “Endangered Species Decision for Sage Grouse Delayed by Congressional Maneuvering.” Northwest Public Radio. December 13, 2014. Online @ http://www.opb.org/news/article/spending-bill-could-delay-sage-grouse-listing/

45. Stoellinger, Temple. “Implications of a greater sage-grouse listing on western energy development.” National Agriculture & Rural Development Policy Center. June 2014. Online @ http://www.nardep.info/uploads/Brief33_ImplicationsListingSageGrouse.pdf

46. Crouse, Bebe. “Conservation Countdown: The Recent Decision on Listing the Greater Sage-grouse.” The Nature Conservancy. Online @ http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/montana/mt-sage-grouse.pdf

47. Freese, Erica. “Cows, insects, and plants: How do they fit in the sage-grouse puzzle?” rangelands.org. Online @ “Cows, insects, and plants: How do they fit in the sage-grouse puzzle?”

48. Strand, Eva K. et al. “Livestock Grazing Effects on Fuel Loads for Wildland Fire in Sagebrush Dominated Ecosystems.” Journal of Rangeland Applications. 2014. Online @ http://journals.lib.uidaho.edu/index.php/jra/article/view/12

49. “Gray Whale.” The Marine Mammal Center. Online @ http://www.marinemammalcenter.org/education/marine-mammal-information/cetaceans/gray-whale.html

50. Murray, Iain. The Really Inconvenient Truths: Seven Environmental Catastrophes Liberals Don’t Want You to Know About — Because The Helped Cause Them.

51. “Delisting Report.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. Accessed online June 2015. Online @ http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public/reports/delisting-report

52. Haapoja, Margaret A. “Hawaii’s Rare Breeds.” The New American. August 22, 2005. Online @ http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Hawaii%27s+rare+breeds:+after+decades+of+solitary+effort+to+save...-a0135579374

53. “Threatened and Endangered Species and the Private Landowner.” U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Accessed January 2015. Online @ http://www.na.fs.fed.us/spfo/pubs/wildlife/endangered/endangered.htm

54. Meltz, Robert. “The Endangered Species Act (ESA) and Claims of Property Rights “Takings.” Congressional Research Service. January 7, 2013. Online @ https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31796.pdf

55. “Continental Shelves.” MarineBio.org. Accessed on June 2015. Online @ http://marinebio.org/oceans/continental-shelve