Vol. 33, No. 06

March 20, 2017

Free Market Healthcare Reform

With health insurance companies being the bane of Americans, it seems silly to suggest that the private sector play a role in fixing the healthcare system, but it must be done. ...

A great healthcare debate is happening in America over whether the healthcare system should be improved via tweaking ObamaCare — a methodology that the new GOP-designed healthcare plan, dubbed the American Health Care Act, seems to be following — or whether an entirely new system should be created. This is one of a series of five articles about how the healthcare system could be changed. The first article, "Healthcare: Which Fix Should We Follow?", explains the goals that a healthcare system should shoot to achieve and lists the four main types of reforms available to the country. The other four articles, including this one, give background and facts about each type of reform and how many goals it would secure. The other articles are entitled "ObamaCare Unraveled," "Government-run Healthcare," and "Does Single-payer Signal a Solution?"

To begin with, in any discussion about the government allowing the private sector to reform healthcare, it should be noted that it is understandable why some Americans have a gut-wrenching visceral reaction against allowing the private sector to try to fix the healthcare system: Insurance companies surely aren’t much in the way of friends of the sick, the poor, or the elderly; insurance companies played a large part in getting us to the disastrous state of healthcare we’re in now; the elderly feel they have pre-paid for Medicare via deductions from their paychecks — and now often desperately need help paying medical bills; and the poor don’t want to rely on private charity for medical care.

A Health-insurance Hammering

Right now, quite frankly, health insurance is a rip-off. Not only is the average premium for family coverage $17,545 per year for employer-sponsored plans in 2016, according to the Kaiser Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, but the deductibles, which average between $1,200 and $2,000 per person, depending on the type of plan, could easily lead to a family going broke — literally. And then there are co-payments to deal with.

Making insurance a much worse deal is the fact that America’s insured often must pay more out-of-pocket for a treatment than someone would pay who was uninsured and negotiated a cash price prior to being treated.

Dr. David Belk, who runs the True Cost of Health Care website and does his own billing for his personal practice, noted that a typical private health insurance company pays a hospital between $300 and $350 for a CT scan of a patient’s head; however, one of Belk’s patients, who had insurance, received approval from his insurer for a CT scan, and then decided not to get it done because the patient’s portion of the scan would have been $1,200. To get his patient the proper care, at a livable price, Dr. Belk found a high-quality local imaging company that was willing to do the scan for $414 if the man paid cash up front. The man would have had to pay $800 extra out-of-pocket if he wanted to use his insurance. Unbelievable, yet true.

Dr. Belk points out that such scenarios are becoming increasingly common. Patients can often negotiate lower prices than they can get through an insurance company, even when the same hospital would be providing the treatment!

At the very least, using insurance, the patient often still pays the bulk of medical bills out-of-pocket — something my wife and I have been finding out about in spades in recent weeks.

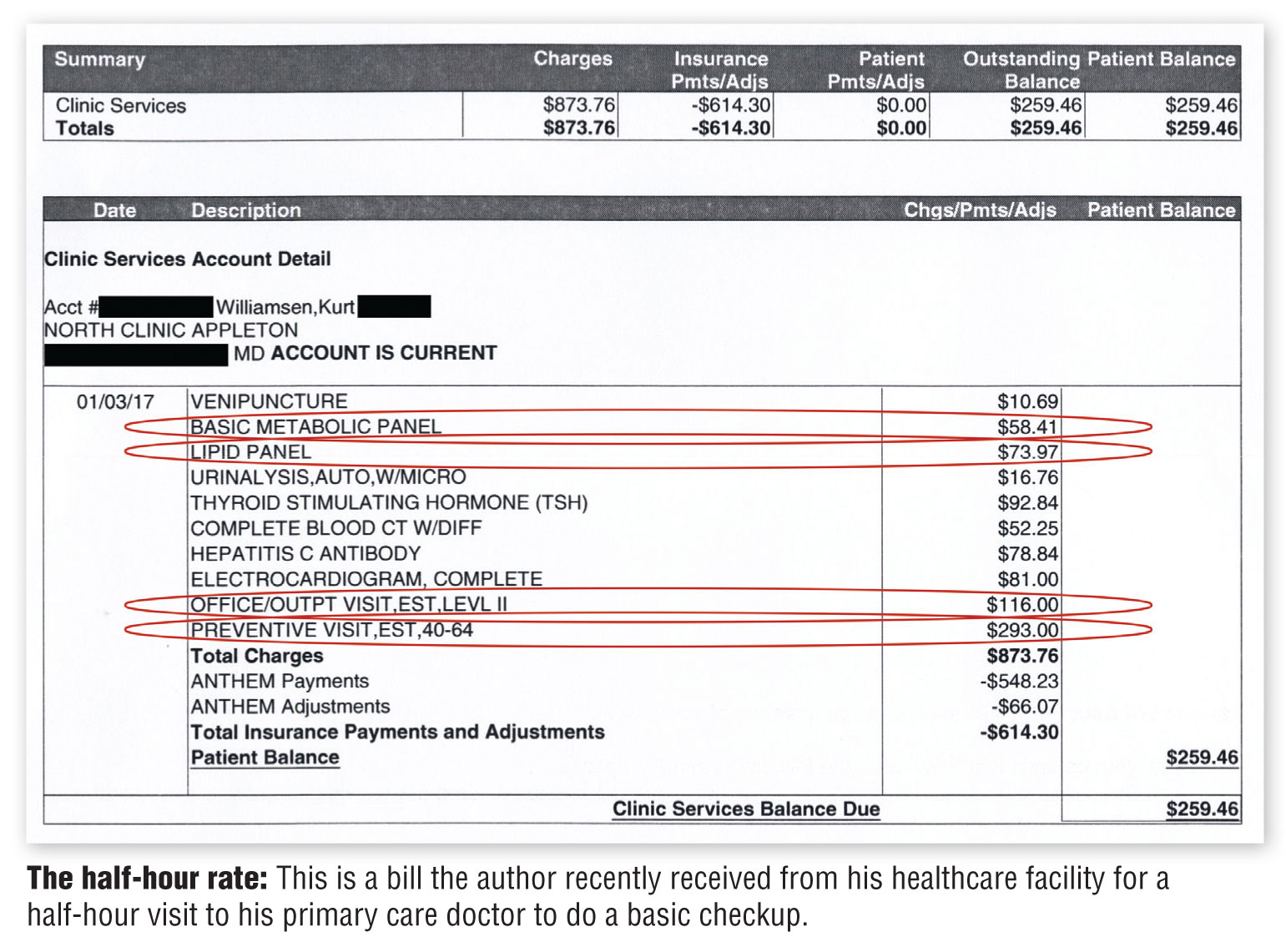

We now owe $2,200 for having had our daughter’s wisdom teeth extracted because the surgeon’s office didn’t tell us until after the surgery that the doctor was out of network, though it knew months before because it had tried to charge our insurance for an X-ray of our daughter’s jaw. My wife had even asked the office to check preauthorization. Additionally, I recently received a bill from a large local medical provider named ThedaCare for my yearly annual checkup, which totaled $873.76 — for about a half-hour visit to my primary care doctor. The sum total of what was done to me was a couple of blood tests, a urine test, a hepatitis C test, and an electrocardiogram (where a nurse sticks a few little electrodes to one’s chest for about a minute to see if the heart is functioning properly). And then my doctor gave me a brief physical exam. I was told at the front desk where I had checked in for the appointment that since it was a preventive visit, I didn’t even need to pay a co-pay. (Apparently under ObamaCare, all preventive visits to the doctor must be covered by insurance.) Yet upon receiving the bill in the mail, I learned that after subtracting “total insurance payments and adjustments,” my out-of-pocket portion of the bill was $259.46. The insurance company’s portion was $548.23.

To me, both figures seemed excessive. They seemed even worse when I found out from the True Cost of Health Care website that my insurance company could have, if it had so chosen, paid the health clinic $237, and the clinic would have considered the amount paid in full and been glad to get it — so much for my insurance company being there to save me money.

The insurance company could have paid so little of the total bill because, for outpatient care, when hospitals and clinics strike deals to accept payments from insurance companies, the insurance companies are allowed to exercise almost complete discretion over how much they will pay for procedures — though they usually at least pay an amount commensurate with what Medicare pays for procedures. Let me explain using the bill I recently received, and tell how insurers and medical providers often work together as co-dependent parasitic entities, deceiving and bleeding patients.

On my itemized bill from my recent checkup, which is shown on this page, circled are some of the charges. The top circled item shows that I received a “basic metabolic panel,” which is a blood test that assesses kidney function and electrolytes, and that I am being charged $58.41 for it. According to Dr. Belk, in his area of California, though hospitals usually “charge” about $179 for a “comprehensive metabolic panel,” which is the same test as a “basic” panel except that it also tests liver function, private insurance actually often pays a hospital $15 (Medicare also pays $15 for such a panel), and hospitals generally consider their charge as “paid in full” upon receiving a $15 payment from either source. (Hospitals accept $12 for a “basic” panel, but the “comprehensive” panel better illustrates my point.) The remainder of the charge is written off completely by the hospital — gone. Let’s look at one more. Next, my blood underwent a “lipid panel,” which according to Belk is “a blood test that checks total cholesterol and breaks it down to good and bad components.” Hospitals near him usually bill this as a $68 procedure, though both private insurance and Medicare actually pay hospitals $19 for this service. My bill for the lipid panel is charged at $73.97. When my insurance company divvied up the bill, I paid $47.18 for the metabolic panel, to satisfy some of my deductible, and the insurance company agreed to pay the entire amount for the lipid panel — all $73.97. Generous of them, wouldn’t you say?

Let me be clear: If my insurer — Anthem BlueCross BlueShield, the second largest health insurer in the country, with in excess of $80 billion in yearly revenue and billions in profits — had so chosen, it could have paid a grand total of $31 for those two tests, and my medical provider would have been willing to call the items paid, but my insurer paid more, and I was forced to pay, as well.

By the way, Dr. Belk knows the low-end amount that insurers are allowed to pay because a company called Multiplan, which manages a network of “almost 900,000 healthcare providers” that are used by companies that self-insure and insurance companies to broaden their physician accessibility, sent him many of the prices. Payment for Medicare services is public knowledge and can be found at CMS.gov.

To learn how we know that $31 is actually a fair payment for those two blood tests, consider the following. According to the website Lab Tests Online, testing blood usually consists of two steps: Put the blood in a centrifuge to separate the plasma and the blood cells and then put the liquid into a machine called a blood analyzer, which does the analysis. The machine uses a few dollars worth of chemicals to process the blood, and a top-of-the-line machine, which can process more than 400 samples per hour, costs $116,350 (used ones are a small fraction of that amount). Very little labor is involved. Using the payment of $31, we find that the machine will be paid for in a little more than 3,800 uses, or in the large medical center I go to, probably less than a month’s time. From that point on, blood tests are almost pure profit. (The machine listed also does other blood tests, such as checking thyroid function, and it analyzes urine samples, making it far more profitable and the time to pay it off far less — and that’s at the uninflated prices!)

Putting the icing on the cake, Dr. Belk shows an advertisement from a blood testing center near him that advertises a price of $95 to draw a person’s blood (venipuncture) and do a metabolic panel, a thyroid count, a cholesterol test, and a urinalysis. Those items on my bill are charged at a total cost of $304.92, nearly all of which my insurance company allowed to be paid by me or it. Is my insurance company — second-largest in the country — fighting for me? No way! Also, keep in mind that the blood-testing center somehow managed to pay for advertising to find customers and did the tests and apparently still made a nice profit.

Looking at my bill again, what’s more odd is that I was charged for two office visits for the same 30-minute appointment: one for a wellness visit at $293, and one for a general office visit at $116, charged because the doctor and I talked about a “health problem” during my wellness visit, and that is not allowed. (Wellness visits must be strictly limited to a brief physical checkup and some blood and urine testing, according to my insurer, as if I knew that ahead of time.) My insurer paid for the entire wellness visit, and it paid $96.09 for the other office visit, when it could have simply told the hospital that my visit wasn’t a wellness visit because the doctor and I discussed my hypertension, and it could have refused to pay the $293 altogether. Odder yet is that the insurer paid a higher amount for the preventive care visit, which is supposed to be a bare-bones checkup, than it paid for the office visit wherein we discussed an actual health problem. Crazy, right?

Too, if I use Dr. Belk’s website, I can add up — based upon his list of normally accepted payment rates — the low end of how much the clinic would have accepted as payment in full from an insurance company for all of the services that I received. Assuming the insurer fought for me (and its own bottom line) and only allowed for one office visit charge (as logic suggests it should do), the total bill would have been $237, or thereabouts. Yes, less than my out-of-pocket payment.

So we have two strange things going on here: The clinic charged a grotesque amount for the care I received, and the insurer paid a large percentage of what the clinic asked for, and it made me pay a bunch as well.

As mentioned earlier, Anthem is the second-largest insurer in the country and could have laid down the law to the clinic about overcharging and refused to pay most of the charges, and the clinic would have had little choice but to concede and accept a lower payment.

Calling Out Collusion

So what’s going on here? In the online video entitled The High Cost of Collusion: Why Healthcare Is So Expensive in the US, Dr. Belk makes a good circumstantial case that health insurers are colluding not only with hospitals but with pharmacies to improve all their bottom lines. He explains that not only do pharmacies such as Walgreens push consumers to buy medicines using insurance, rather than abstaining and paying cash — benefiting both Walgreens and the insurers — but insurers actually benefit when they pay more than minimal amounts toward many hospital bills (bills that are grossly inflated). By overpaying some bills (not all bills, or insurers would go broke) insurers not only boost their future profits, they convince Americans that it would be suicidal to live without insurance (consider it a form of advertising).

The way insurers benefit by overpaying has to do with the fact that if insurance companies pay out a certain percentage of their health premiums on medical care, they can raise insurance premiums the following year and make more total profits. Here’s how it works: For years insurers have tried to convince the public that they are good stewards of monies by advertising their “medical loss ratios” — essentially the percentage of the premiums they collect that they actually spend on people’s medical bills. Typically, insurers want to show that they spend between 80 and 85 percent of premiums on medical care (leaving 15 to 20 percent to cover costs and make a profit). So to make more profit the following year, insurers need to raise the amount of premiums they collect. Mathematically speaking, for every dollar insurers spend above a certain medical loss ratio, they get to raise their premiums by $1.20. Not a bad deal if you can get it.

Hospitals, of course, benefit from higher insurer payments, and so they have no reason to disrupt the system.

Looking at how my own bill was paid, there doesn’t seem to be another rational explanation besides collusion for how items are billed and paid. At the very least, it is clearly apparent that my insurer is not looking after my best interests. Moreover, all of the economic incentives, as the system is presently set up, will inevitably drive healthcare costs higher yet, which the country and the people in it cannot afford. So the system needs to be changed.

And though health insurance verges on being a criminal enterprise, the free market is where the fix must come from.

Not only must the free market be allowed to fix the system because — as we have seen in the other healthcare articles in this issue — government-controlled plans are doomed to fail, but the free market is not to blame for the dysfunction in the medical marketplace. The dysfunction was/is caused because entities strove to cancel out free market incentives in medical care, and they were successful.

In fact, blaming problems in healthcare on the free market seems nearly ludicrous when one realizes that there is virtually no free market in healthcare — it is controlled and largely run by government. Goodman estimates that the U.S. system is 80-percent similar to most other systems in the world.

As for health insurance, it’s not really surprising that insurers don’t watch out for the well-being of Americans in general because that wasn’t among the functions that the largest insurance companies were created to accomplish. As Goodman related in Priceless,

BlueCross was essentially created by the hospitals, and BlueShield was created by the doctors. In both cases, the objective was the same: drive the commercial insurers out of the market and establish health insurance that saw its purpose as (1) making sure everyone was insured and (2) making sure providers were paid enough to cover the cost of services. (You can think of this as private-sector socialism.) To achieve the first goal, the typical BlueCross plan practiced community rating (charging everyone the same premium regardless of health condition) and accepted all applicants, regardless of pre-existing conditions. To achieve the second goal … if BlueCross patients constituted 50 percent of the patient bed-days for a hospital, BlueCross agreed to pay 50 percent of the hospital’s annual expenses.

After some favorable legislative votes in statehouses, we got the system we have now — because all the insurers had to play, and pay, the BlueCross way, or they were put out of business.

Doctors and hospitals created the present insurance system to their benefit, and they lobbied statehouses to ensure the system continued to benefit both groups. One of the most important of those lobbying efforts was to eliminate competition — virtually eliminating the chance the system would ever remedy itself via the actions of the marketplace and consumers — through lobbying for something called a Certificate of Need (CON). Most states have CON laws on the books (the federal government had them but eliminated them in 1986), which restrict the construction of new healthcare facilities unless it can be demonstrated to state entities that additional facilities are needed (and the state entities are run by people in the medical community). The American Medical Association also managed to gain the power to certify medical schools, which the AMA used to limit the number of new doctors and drive up doctor pay.

Exacerbating the problems is the fact that both state and federal governments decided that they knew better than their citizens what type of health coverage they should be paying for, and they started mandating that certain benefits had to be included in health plans, many of which didn’t have to do with “wellness.” As Goodman put it, diabetics had “to pay for other people’s in vitro fertilization, naturopathy, acupuncture, or marriage counseling, in order to obtain diabetic care.” That many of the mandated benefits likely reflected acquiescence to lobbyists’ demands is evident by the fact that the federal government has literally made contraception a political issue, fighting lawsuit after lawsuit for infringing on Americans’ religious liberties, though contraceptives are generally so inexpensive that nearly every American could afford to purchase them out-of-pocket.

Those legislation-provided goody lists come at a price, as Goodman indicated: “Studies show that as many as one out of four uninsured Americans — most of them healthy — have been priced out of the market for health insurance by cost-increasing mandated benefits.”

Then there are federal laws allowing pharmaceutical companies to extend patents on medicines so that the drugs don’t achieve “generic” status, the fact that the FDA is almost entirely controlled by ex-executives of the largest pharmaceutical companies (and how they rig the system), and more — much more. Government has driven up costs via mandates, regulations, industry-protecting laws, etc.

Free Market Fixes

On a positive note, there are also ideas to fix all these things, and “proof of concept” that the private sector — if unleashed — could remedy the issues:

• Over the past two decades, the inflation-adjusted price of cosmetic surgery has dropped, not increased. Cosmetic surgery is one of the few medical procedures where patients pay out-of-pocket and doctors compete for business.

• From 1999 to 2011, the price for conventional LASIK has dropped dramatically. Nowadays, if doctors want to charge year 1999 fees for LASIK, they must provide the very latest in custom LASIK, with much greater quality. This is strong evidence that abundant and hi-tech equipment does not necessarily lead to rapidly rising healthcare costs, as groups such as Physicians for a National Health Program have claimed.

• Anyone willing to travel to get surgery can usually bargain to get steeply discounted rates. Medibid, a company that finds discounted surgical prices for American customers, listed a price for total knee replacement of $12,000, though insurance companies paid on average $32,500 for the same procedure (in the Dallas area), according to Goodman, while a company called North American Surgery had the cash price for knee replacement at $16,000 to $19,000.

• The Surgery Center of Oklahoma lists cash prices for surgeries on its website that are often lower than what a patient would pay in health insurance deductibles/- co-pays.

• Walk-in clinics and mail-order drug companies compete on price, as do Walmart and Costco pharmacies.

• And as Goodman learned: Because of their efficiency, “studies by researchers at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice imply that if everyone in America went to the Mayo Clinic [arguably one of the finest medical institutes in the world] for healthcare, the nation could reduce its annual healthcare bill by one-fourth. If everyone went to Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, the nation could reduce its healthcare spending by one-third.”

So the question becomes, “Can the private-sector fix attain our ideal healthcare criteria?” Here are some possible ways that the answer could be yes.

Creating “portable” insurance that lasts a lifetime — The number one method to prompt portability is through changing the tax laws. At present, employers can buy health insurance with before-tax dollars, while people who buy insurance in the individual market must use after-tax dollars, “effectively doubling the after-tax price for middle-income families,” per Goodman. Changing the tax laws would loose insurance from employment, allowing people to keep their insurance and change jobs. This one change alone would give many uninsured the capability to obtain health insurance. To make insurance last a lifetime, government should allow tax-free health savings accounts (HSAs) to pay for Americans’ insurance and any out-of-pocket medical expenses. Insurance companies should be encouraged to provide insurance in case one’s health status changes and one needs to change insurance plans. These HSAs should be allowed to roll over at the end of the year so that in years Americans are healthy, they are saving — and collecting interest — for years that they are not. For constitutionalists, who are aware that nothing in the Constitution allows the federal government to be involved in any aspect of healthcare whatsoever, lifelong HSAs would mean that within a generation most Americans would eventually not need Medicare, and government could be phased out of the healthcare business. There are also several methods whereby Medicare costs could be lowered by allowing those Americans in or nearing retirement, and relying on Medicare, to use monies that would be spent on their healthcare to fund private coverage — again, if they so choose. (Those methods are too detailed to go into here.)

Paying for health insurance after becoming ill or injured — As mentioned above, health insurance companies should be encouraged to sell insurance that continues paying for life insurance premiums should one become incapacitated.

Making medical care affordable — The primary steps to making medical care affordable involve eliminating Certificate of Need laws and encouraging transparency in insurance payments. Getting rid of CON laws would allow enterprises such as the Surgery Center of Oklahoma to flourish around the country and bring competition back into healthcare. To add impetus to bringing back competition in healthcare, since nonprofit hospitals don’t pay taxes, we might take away “nonprofit” status from hospitals that don’t post cash prices for non-third-party payers, prices commensurate with the lowest amounts hospitals would accept from insurance companies (the logic being that “nonprofit” implies that a business acts in the public good). If given the low end of prices that insurance companies are allowed to pay hospitals, along with HSAs, the great bulk of Americans could relatively easily pay for most medical costs out-of-pocket, and so they would only need health insurance against catastrophic illness or injury, causing premiums and total healthcare costs to plummet. Also, another action that would likely prompt the health insurance industry to cater to consumers would be to eliminate them from any role in the public provision of healthcare — either Medicare or Medicaid policies. (Remember that insurance companies lobbied for ObamaCare because the ACA forced Americans to buy health insurance and it promised guaranteed profits.) Too, the role that the FDA plays should be taken over by a private enterprise akin to Underwriters Laboratory, a global independent safety science company that certifies as safe items such as electronics, and drug patent laws need to be rewritten.

Making healthcare accessible by rich and poor alike and eliminating rationing — As was mentioned in previous articles, though governments can nominally provide health insurance, they can’t necessarily provide access to care, so “equal access to healthcare” really means scattered accessibility to treatments that the government makes available, rather than access to treatments patients really want when they want them. If the above changes were made, they would cause healthcare costs to drop drastically and provide a method through tax-law changes and HSAs wherein most everyone could afford care. Furthermore, the dwindling number of primary care doctors needs to be remedied. This can be done by allowing more foreign doctors into the United States (if they pass medical competency tests) and getting the AMA out of certifying medical programs. Every year many students who have passed medical school cannot find a hospital residency program to enroll in — and that’s wrong on every level.

Improving quality and keeping it high — Referencing the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, it should be noted that with a high reliance on cash-paying patients, the Surgery Center is highly motivated to avoid things such as postoperative infections. Its rate is near zero, compared with four to 10 percent in the medical community at large. Not surprisingly in a competitive environment, “quality” is a selling point.

These are just a smattering of the available suggestions to attain as good a healthcare system as possible in an imperfect world. There are many more available from John Goodman with the Independent Institute, Sally Pipes with the Pacific Research Institute, Michael Tanner with the Cato Institute, Robert Moffit with the Center for Health Policy Studies, Steven Trobiani in his book Sustainable Healthcare Reform, Twila Brase with Citizens’ Council for Health Freedom, Robert F. Graboyes’ article “Fortress and Frontier in American Health Care,” and more.