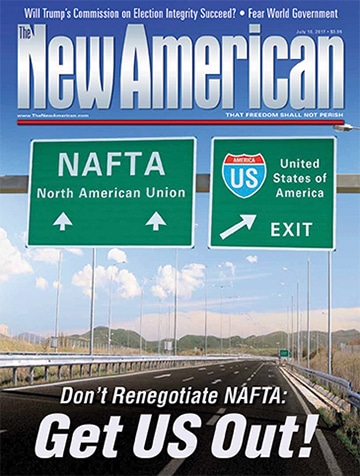

Don’t Renegotiate NAFTA: Get US Out!

While running for the oval office, President Trump noted to crowds how destructive NAFTA was to individuals, businesses, and states. Now he says he may keep NAFTA.

On New Year’s Day in 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into being. Despite the enthusiastic backing of then-President Clinton, congressional Democrats, and a large majority of Beltway Republicans, the massive new trade deal and international bloc that it created were controversial everywhere but inside the Beltway.

As discerning observers almost a quarter-century ago pointed out, although NAFTA was being sold to the American public as a “free trade” deal, it was in fact anything but. Its beguiling name notwithstanding, NAFTA was and remains a “managed trade” deal, an instrument of international socialism setting up a vast new array of international bureaucracies to manage the flow of goods across the borders of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Included in the deal from the very get-go, for example, was a sweeping set of environmental objectives and rules in a little-noticed side agreement, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, whose enforcement arm is the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, headquartered in Montreal, whose mission is to receive and adjudicate notices of alleged environmental violations by any of the three North American countries.

During its 23-year lifespan, NAFTA has brought about radical changes in the economies of the three North American countries, of which the most conspicuous has been the proliferation of maquiladoras, Mexico-based assembly plants, mostly built by American companies moving assets south of the border, where wages are cheaper and government regulations less burdensome. NAFTA has thus been an enormous economic boon for Mexico, a poor country run by an irredeemably corrupt government — which now has the manufacturing base of a major industrial power. The United States, on the other hand, has experienced a massive exodus of jobs and capital as hundreds of American businesses have moved assets south of the border.

NAFTA has failed to deliver on the airy-fairy promises of its creators, at least from the point of view of its most important sponsors, American taxpayers. And despite its dismal track record, the organization is in no imminent danger of collapse, now that President Trump has decided, after months of anti-NAFTA campaign bluster, to renegotiate rather than withdraw from the organization. Trump’s top priority, as with most of his foreign policy priorities, is to get a better deal for the United States. But extracting better trade terms from our two North American neighbors has virtually nothing to do with the long-term objectives of NAFTA. Not only is NAFTA not a free-trade agreement, its underlying purpose is not trade at all. Like the former European Common Market — which was transformed into the European Community and finally into the modern European Union, a full-fledged continental government — NAFTA was designed with much more ambitious aims in mind than making the world safer for imported avocados and Canadian softwood. And President Trump, by deciding to stick with and further legitimize NAFTA, has — wittingly or unwittingly — greatly improved the prospects for NAFTA to someday be transformed into a North American Union.

Candidate Trump portrayed himself as the NAFTAnator, a new type of president with ordinary Americans as his top priority, who would not hesitate to withdraw from “one of the worst deals our country has ever made,” as he called NAFTA on May 9, 2016. On the hustings in August in North Carolina, Trump told an enthusiastic crowd, “I see the carnage that NAFTA has caused, I see the carnage. It’s been horrible. I see upstate New York, I see North Carolina, but I see every state. You look at New England. New England got really whacked. New England got hit.” A core element in Trump’s stump speech, NAFTA was a calamity he routinely blamed on President Bill Clinton — and by extension, his rival, “Crooked Hillary.” Indeed, President Clinton signed NAFTA into law, but it was his predecessor, patrician Republican George H.W. Bush, who negotiated and signed the agreement on the international stage. Also on board with NAFTA was most of the Republican congressional delegation in 1993-1994, including future GOP Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

In a word, NAFTA was never a Big Government boondoggle imposed on an unwilling but valiantly resistant GOP minority by venal Democrats; it was and remains a product of bipartisan consensus, at least among the elites in control of both parties. For Trump to attempt to rally GOP leadership against an organization they were complicit in creating was a nonstarter.

It therefore was not terribly surprising to seasoned observers when President Trump, on April 26, announced that, all previous anti-NAFTA billingsgate notwithstanding, he had decided to renegotiate rather than withdraw from NAFTA. In the first of two Tweets, the president admitted to having a change of heart after receiving personal calls from both Canada’s Justin Trudeau and Mexico’s Enrique Peña Nieto: “I received calls from the President of Mexico and the Prime Minister of Canada asking to renegotiate NAFTA rather than terminate. I agreed.” But then, in an apparent sop to disappointed anti-NAFTA Trump supporters, the president Tweeted reassuringly: “... subject to the fact that if we do not reach a fair deal for all, we will then terminate NAFTA. Relationships are good — deal very possible!” Later he reiterated his position to reporters following a meeting with Argentine President Maurice Macri:

I decided rather than terminating NAFTA, which would be a pretty big, you know, shock to the system, we will renegotiate. Now ... if I’m unable to make a fair deal for the United States, meaning a fair deal for our workers and our companies, I will terminate NAFTA. But we’re going to give renegotiation a good, strong shot.

European Union

Whether President Trump truly believes renegotiating NAFTA could possibly benefit Americans is not for us to speculate. This author finds it difficult to believe, however, that President Trump can possibly be unaware of what internationalist elites have foisted on Europeans in the name of free trade; the entire European unification scheme has unfolded in the course of Trump’s lifetime, and is worth recalling here as a cautionary tale.

In 1951, when Donald Trump was five years old, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was set up by six Western European countries under the Treaty of Paris. Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, France, and Luxembourg created the very first modern supranational organization — an apparently innocuous, narrowly focused trade bloc that began the process that has led to the political integration of much of Europe under the modern European Union. Note well: The European Union has abandoned any pretense of being a “free trade” union; its sponsors now openly tout it as a regional government, and have long since moved on from questions of economic and monetary union to total political and legal union — in other words, a modern-day pan-European empire such as Rome or Napoleonic France, but assembled largely with the consent of its subject peoples rather than by naked military conquest.

Nor did this come about by chance. It is well documented that the political unification of Europe has long been the objective of European elites. Before the Second World War was even over, French financier and pioneering internationalist Jean Monnet, the “father of Europe,” was already working to lay the foundation for a postwar order that contemplated the eventual economic and political unification of Europe. Born into a well-to-do French family of cognac manufacturers, Monnet as a young man was one of the founders of the now-defunct League of Nations, and was appointed the organization’s first deputy secretary-general. However, he soon grew impatient with that organization’s stifling bureaucracy, and returned to the family business and to international finance, where he learned the art of currency stabilization in the new post-gold standard world. A real-life “international man of mystery,” Monnet spent time in Poland, Romania, and China in the interwar years helping to stabilize economies and, in the case of China, even reorganized that country’s railroad system. By the time of the outbreak of World War II, Monnet had become as much an Englishman as a Frenchman, and was instrumental in helping those two governments forge an alliance against the Axis.

Despite his impeccable globalist credentials, Monnet remained a European at heart, and it was with the affairs of Europe that he was chiefly concerned. In 1943, in an address to the National Liberation Committee, the seat of the French government in exile in Algiers, Monnet appears to have articulated for the first time his overarching goal, that of a unified Europe:

There will be no peace in Europe, if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty.... The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the necessary prosperity and social development. The European states must constitute themselves into a federation.

Following the war’s conclusion, Monnet and his associates arranged for the dismantlement of the German industrial base, particularly the seizure by France of the German coal mines in the Ruhr and the Saar. These critical assets were then offered back to Germany at a price: submission to a new international authority, a “High Authority,” that would exercise control over the coal and steel assets of all member nations, including both France and Germany. Having little choice, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer accepted the new order. French Minister of Foreign Affairs Robert Schuman proclaimed at the time:

Through the consolidation of basic production and the institution of a new High Authority, whose decisions will bind France, Germany and the other countries that join, this proposal represents the first concrete step towards a European federation, imperative for the preservation of peace.

Thus the new European Coal and Steel Community from the outset was openly intended to be the first of a series of steps leading to the unification of Europe under a single political authority. Jean Monnet was appointed the first president of the ECSC’s High Authority in 1953, where he immediately began laboring for something larger. In 1955, he founded the Action Committee for the United States of Europe.

As intended, the European Coal and Steel Community was soon overshadowed by a more ambitious organization. In 1958, the European Economic Community (EEC, the “Common Market”) came into being, a broader trade zone that originally consisted of the same six member nations of the ECSC but actively sought to add more, with the transparent objective of eventually including all of Western Europe. Alongside the ECSC and the EEC, a third organization, the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM), operated in concert to draw in other European nations to the budding unification project. In 1967, these three communities were unified under the Merger Treaty.

The 1970s were a banner decade for European unification. In that decade, new countries, including the U.K., joined the EEC, and enormous progress was made toward long-sought political unification. By the end of the decade, a fully functional, if not yet very powerful, European Parliament was operational. By 1980, no sober observer could doubt the true motives of the “Eurocrats.”

The project of European unification has not gone forward without opposition. As early as the 1950s, many in Europe objected to the severe compromises of national sovereignty that were being proposed. Such objections, often voiced by powerful nationalist interests such as trade unions, managed to delay the designs of Monnet and his ideological successors, but in the long run, have not stopped European unification from coming about.

In 1993, the year the Maastricht Treaty came into effect, the European Economic Community shortened its name to the European Community (EC), a name that embraced the all-encompassing vision of its founders. The same treaty also created the European Union (EU) out of the three existing European communities. With the European Union a political reality, movement toward total continental political, economic, and financial integration accelerated. In 1998, the European Central Bank (ECB) was created, and the euro, the currency of united Europe, was launched the following year to worldwide plaudits. In 2009, the old European communities, including the EC, were officially dissolved within the EU via the Treaty of Lisbon. Despite the ongoing sovereign debt crisis in Europe, the union shows no signs of falling apart. The goal all along, after all, has been political unification, not shared economic prosperity, and the gradual leveling of Europe’s once-sovereign economies is of little concern to the internationalist ideologues responsible for cobbling together the world’s first international government-by-consent.

Today’s Europe is, if not yet a fully integrated superstate, certainly no longer a collection of sovereign nations. The European Union now controls European finances via the ECB and the euro; has completely open borders, facilitating not only the flow of goods and services but also illegal immigrants and malefactors such as Islamic terrorists across former international borders; issues a broad range of regulations, including environmental and commercial statutes; has an active European parliament whose legislation is binding on member countries (albeit one whose job is mainly to rubber-stamp already-authorized rules and regulations issued by EU bureaucrats); and is working diligently to establish European taxes, a single European police force, military, and the like. What was 30 years ago considered the province of wild-eyed speculation and dystopian conspiracy theory has become 21st-century reality for hundreds of millions of Europeans who now owe their allegiance not to their respective motherlands but to a continent-wide government.

But what possible purpose could there be in cobbling together a European Union? To facilitate the creation of a single global government, a project near and dear to the hearts of international socialists for more than two centuries. Creating a workable world government by persuading nearly 200 separate sovereign countries to give up their sovereignty is obviously impractical — unless the nations of the world could first be persuaded to form regional political unions with countries with whom they already share history, culture, legal traditions, and the like. Several such regional unions could then be merged into a single global estate with comparative ease.

North American Union

The process of continent-wide unification began in North America with the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement of 1989. At the time, few voices were raised in opposition to this apparently innocuous agreement between two very close allies with an enormous flow of goods across one of the world’s longest borders. But artfully included in the text of the treaty were provisions to “lay the foundation for further bilateral and multilateral cooperation to expand and enhance the benefits of the agreement.” A single word, “multilateral,” betrayed the longer-term aims of the treaty: Other countries were eventually to be brought into this “free trade” zone, in a rhetorical sleight of hand reminiscent of the manner in which the original EEC was used to draw other European countries into the Common Market in addition to the six founding nations.

The ink was not even dry on the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement when negotiations began in earnest to create a broader “free trade zone” that would include Mexico. The so-called North American Free Trade Agreement took only two years to negotiate, and was signed in 1992 by American President George H. W. Bush, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and Mexican President Carlos Salinas. Already by October 1992, The John Birch Society was opposing NAFTA on the basis that it would “create a regional government-in-waiting.” However, Congress went on to approve the “trade agreement” late in 1993. It was signed by President Bill Clinton later in 1993 and went into effect in 1994.

Of course, North America does not end with Mexico, and a few years after NAFTA went into effect, negotiations began to create a separate United States-Central American “free trade zone,” which would include Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, as well as the United States. After much negotiation, the Central American Free Trade Area (CAFTA) was ratified by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2005, and went into effect in 2006. Subsequently, the Caribbean nation of the Dominican Republic has joined CAFTA.

In fact, during the last few decades “free trade” has broken out all across the Americas. In 1991, Mercosur, a customs union and “free trade zone” encompassing much of South America, was founded. Mercosur today includes the nations of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela (which was recently suspended due to political and economic turmoil in that country). Meanwhile, the Andean nations of Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru belong to the Andean Community, a “free trade bloc” transparently inspired by and named after the European Community. These two trading blocs are now subordinate to the Union of South American Nations (USAN, or UNASUR in Spanish), a European Union-like political union that encompasses all 12 South American countries. UNASUR came into being only six years ago, but has already made considerable progress toward continent-wide integration. UNASUR boasts a parliament, a bank (the Bank of the South), and a wide range of councils dealing with matters as diverse as health, defense, energy, education, and culture. In other words, UNASUR is following the European playbook exactly, and is at roughly the same phase of implementation as the European Union was 30 years ago.

Even the English-speaking Caribbean nations (including Belize, technically part of Central America) have a “Caribbean Community” (CARICOM) that began as a Caribbean Free Trade Area (CARIFTA) back in the 1960s.

With the examples of Europe and South America to instruct us, there can be no possible doubt that a North American Union, along the lines of the European Union and UNASUR (as well as other embryonic regional governments overseas, such as the African Union), is planned, the strenuous denials of internationalists notwithstanding. There has been one ambitious attempt at wider unification already, the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which was launched in 1994, scant months after NAFTA went into effect. The FTAA contemplated unifying North, Central, South, and Caribbean America into a single “free trade zone,” with the usual provisions for further integration down the road. After 11 years of negotiations, however, the FTAA foundered and fell apart in 2005. Although 26 of the 34 countries that attended the last FTAA summit, held at Mar del Plata, Argentina, in November 2005, pledged to meet again in 2006, that next summit never happened. Not coincidentally, The John Birch Society had kicked off a vigorous campaign to stop the FTAA by warning its members in May 2000 that the FTAA would be “a step toward transforming NAFTA into a full-scale hemispheric version of the European Union.” By 2005, the JBS had succeeded in shutting down the internationalists’ dream of establishing a bicontinental government bloc in the Western hemisphere.

As for the quest for a North American Union (NAU) per se, the feverish desire of many internationalists to transform NAFTA into a true North American political union á la EU is well documented. Former Mexican President Vicente Fox, for example, agitated openly about the need for using NAFTA to springboard North America into deeper integration, a so-called NAFTA Plus plan that contemplated, among other things, a completely open U.S.-Mexico border. In a candid 2001 interview, Fox held forth with an American interviewer on the need for “convergence of our two economies, convergence on the basic and fundamental variables of the economy, convergence on rates of interest, convergence on income of people, convergence on salaries.” While lamenting that this might take time, he went on to express hope for future policies that would “erase that border, open up that border for [the] free flow of products, merchandises, [and] capital as well as people,” and noted that Mexico stood to benefit from such an arrangement in much the same way as erstwhile weak economies such as those of Ireland and Spain had benefited from membership in the European Union.

The late Robert Pastor, a Latin American expert and member of President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Council staff — and also of the flagrantly globalist Council on Foreign Relations — made a late-life career out of agitating for what he coyly termed a “North American Community.” Pastor insisted that this was not the same as a “North American Union,” nor was in any way inspired by the European Union. Yet his ideas, and those of other “North Americanists,” argue otherwise. Major long-term agenda items include a North American currency union, featuring a currency to be known (not surprisingly) as the “amero”; a North American customs union, such as was implemented in the early stages of the European Community; and various schemes for the harmonization of wages, labor standards, environmental laws, and border security, among many other things.

Nor is a North American Union merely a pipe dream of foreign politicians and think-tank theoreticians. Henry Kissinger, former secretary of state to presidents Nixon and Ford and an arch-internationalist insider, in a 1993 Los Angeles Times article, approvingly styled NAFTA as “the most creative step towards a new world order taken by any group of countries since the end of the Cold War,” pointing out that NAFTA “is not a conventional trade agreement, but the architecture of a new international system.”

As evidence of just how deep-seated the consensus on “North Americanism” is among Washington policy elites, whose concerns are utterly remote from those of the American private sector, consider the frank discussion on how to proceed with continental integration in a 2005 American diplomatic cable, released by WikiLeaks in 2011. In the cable, marked “sensitive,” American diplomatic personnel in Canada assess the prospects for further North American integration, based on circumstances in Canada:

An incremental and pragmatic package of tasks for a new North American Initiative (NAI) will likely gain the most support among Canadian policymakers. Our research leads us to conclude that such a package should tackle both “security” and “prosperity” goals. This fits the recommendations of Canadian economists who have assessed the options for continental integration. While in principle many of them support more ambitious integration goals, like a customs union/single market and/or single currency, most believe the incremental approach is most appropriate at this time, and all agree that it helps pave the way to these goals if and when North Americans choose to pursue them.

The cable discusses in considerable detail the need for such measures as a common currency and customs union, and notes that these, and other recommendations, are strongly supported by Canadian policy elites. The entire concern of the document is with how American and Canadian elites can align their policy goals; that no mention whatever is made of any concerns American and Canadian citizens might have at their countries’ being corralled into this “North American Initiative” is indicative of how completely irrelevant such concerns are to the unelected policy elites who are the true nexus of modern American political power.

Despite all of the momentum behind the internationalists’ NAU project, The John Birch Society managed to inflict a major setback on the construction of the NAU by defeating the Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP) initiative. In March of 2005, President George W. Bush and the leaders of Canada and Mexico announced the formation of the Security and Prosperity Partnership, a trilateral cooperative effort with the hidden goal of transforming NAFTA into the NAU. A couple months later, the Council on Foreign Relations published Building a North American Community, a blueprint for transforming NAFTA into the NAU via the SPP.

In October 2005, The John Birch Society launched a STOP the SPP campaign. Four years later the internationalists were forced to abandon their SPP/NAU initiative. Then, in 2011, Robert Pastor published The North American Idea: A Vision of a Continental Future, in which he specifically named “the John Birch Society” as among the leading groups that “have been the most vocal, active and intense on North American issues, and they were effective in inhibiting the Bush administration and deterring the Obama administration from any grand initiatives.”

Don’t Renegotiate NAFTA — Get US Out!

With the announcement by the Trump administration of its intent to renegotiate rather than withdraw from NAFTA, the JBS is redoubling its efforts to raise public awareness of the true nature of NAFTA. On May 23, the JBS wrote “Don’t Renegotiate — Get US Out! of NAFTA,” posted at JBS.org:

On April 27 President Trump announced he had decided to renegotiate NAFTA rather than withdraw.... Negotiations could begin as early as August 16 and could be complete by the end of 2017. What happened?... Although we do not have inside knowledge of the details of why Trump changed his mind, it is pretty easy to understand the generalities of the sudden change of heart.... Donald Trump had run smack-dab into one of the internationalist establishment’s most important steppingstones toward world government, the North American Union (NAU). The NAFTA agreement represents the foundation of the eventual North American Union, a supranational governmental entity that would be comprised of the three formerly sovereign nations.... The NAU is modeled after the internationalist establishment’s highly successful, although hugely deceptive, project to establish the European Union via so-called free trade agreements. Since many of Trump’s advisors are members in good standing of the internationalist establishment, no wonder they advised him very powerfully to forget about withdrawing from NAFTA and instead work on renegotiating the agreement. In fact, they already had been planning to update NAFTA.

Now that we’ve withdrawn from the TPP, renegotiating NAFTA is exactly what they want as a next step toward regional government, aka the North American Union (NAU), on the way toward world government under the United Nations.

President Trump, it would appear, has some appreciation for NAFTA’s deleterious economic effects. But — despite his pledges to put America first — he has shown little interest, so far, in the far greater threat to American independence entailed by our continued membership in the organization. Let us hope that better-informed and -intentioned ordinary Americans will eventually get America out of NAFTA altogether and stop the North American Union.

This article originally appeared in the July 10, 2017 print edition of The New American.