Vol. 33, No. 06

March 20, 2017

Does Single-payer Signal a Solution?

Single-payer healthcare — such as Canada has — is sold with promises of low costs, abundant care, and high quality. But do the claims stack up to scrutiny? ...

A great healthcare debate is happening in America over whether the healthcare system should be improved via tweaking ObamaCare — a methodology that the new GOP-designed healthcare plan, dubbed the American Health Care Act, seems to be following — or whether an entirely new system should be created. This is one of a series of five articles about how the healthcare system could be changed. The first article, "Healthcare: Which Fix Should We Follow?", explains the goals that a healthcare system should shoot to achieve and lists the four main types of reforms available to the country. The other four articles, including this one, give background and facts about each type of reform and how many goals it would secure. The other articles are entitled "ObamaCare Unraveled," "Government-run Healthcare," and "Free Market Healthcare Reform."

According to Physicians for a National Health Program, creating a healthcare program that operates as a Medicare system for all would not only rid Americans of all of the costs associated with health insurance companies (since those companies would not be allowed to compete with the government public system), it would fund all of the medically necessary healthcare needs for all Americans — and have enough money left over for care for the aged in long-term care facilities. The plan’s proponents advertise that it would meet all the criteria of an ideal health system: It would provide cradle-to-grave care; no one would go broke in paying for care; it would not raise costs any higher than they are now; rich and poor alike would get equal access; and quality would remain high.

Here’s how it would be set up: The U.S. government would create a system that is set up like Medicare, except it would be without deductibles and co-payments and it would cover “all medically necessary services, including: doctor, hospital, preventive, long-term care, mental health, reproductive health care, dental, vision, prescription drug and medical supply costs.” The plan would pay private doctors an agreed upon amount for services rendered, as determined by a health planning board made up of patient representatives and medical experts. (“The representatives would decide on what treatments, medications and services should be covered, based on community needs and medical science.”) Patients could go to any doctor they desired. Using savings generated by eliminating insurance companies’ administrative and overhead costs — presumed to be in excess of $500 billion per year — and monies already spent by governments on healthcare, all necessary physical and mental care for every American would be paid for (for the same cost as our present system). To ensure that the system isn’t undermined by wealthy Americans, private individuals would be legally forbidden from purchasing from outside the system any medical service covered by the government. Also to bolster the system, the health planning board would have the power to allocate all medical equipment in the country to where it is needed, and no medical practice could purchase capital equipment — think “CT scanners, MRI scanners, and surgery suites” — without permission from the board.

The website of Physicians for a National Health Program makes it sound as if its plan is a no-brainer: It will simplify everyone’s lives, and completely eliminate the fear of huge medical bills. It will cost the same as at present, without the giant yearly increases; it will let doctors make doctor-decisions without interference; and it guarantees equality of care and even pharmaceutical needs. But is it that easy?

In a word: no.

It Isn’t That Easy

In fact, most of the claims are little more than a pipedream. For instance, a few of the biggies that undergird the entire rationale behind the government-provided care — that rich and poor will get equal care and that quality of care and access to care will improve — are simply false.

Just because a governmental entity promises to pay a person’s medical bills doesn’t mean that that person can actually obtain medical care. Massachusetts introduced a healthcare plan that, while not a single-payer system, was the model for ObamaCare, and when subsidized care was provided, the waiting time to see doctors grew dramatically. As John Goodman says in Priceless, “The waiting time to see a new family practice doctor in Boston is longer than any other major U.S. city. In a sense, a new patient seeking care in Boston has less access to care than new patients anywhere else.” He adds:

In Britain, 50 years after the National Health Service was formed to rid the country of healthcare inequality in the country, a government task force released the Atcheson Report, which found that inequality was worse than when NHS began, noting that there are vastly differing survival rates, depending on whether a person lives in a wealthy neighborhood or a poor neighborhood.

Meanwhile, in Canada, the vast majority of doctors admitted in a survey that they had given preferential treatment to certain patients, including celebrities and people who were in politics (and that’s only the doctors who admitted it).

In a related vein, Goodman makes the point that though Americans are repeatedly told that care in Canada is as good or better than in the United States, Americans in general get more time with their doctor than people in other systems do, and uninsured Americans receive more preventive screenings than insured Canadians do.

Thirty percent of Americans get more than 20 minutes with their doctor, as opposed to 20 percent of Canadians, 12 percent of Australians, and five percent of the British. (Is less time with a doctor really as good, or better?)

As to the tests, the percent of women over a five-year time-span who have had a cervical cancer screening in Canada is 80 percent, and for America’s uninsured it is 80 percent, while for the U.S. insured it is 92 percent.

A similar discrepancy holds true for women between the ages of 40 and 64 having a mammogram within five years: 65 percent both for Canadians and America’s uninsured, and 87 percent for U.S. insured. Almost twice as many U.S. uninsured men have had a prostate cancer test as compared to Canadians, and far more American men and women have ever had a colonoscopy. Too, the United States has the best five-year survival rates for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer.

In Canada, 27 percent of patients need to wait four months or more for elective surgery; in Britain it’s 30 percent and in the United States it’s eight percent — though U.S. times are becoming longer as more people enroll in government healthcare programs. And Brits and Canadians have far “less access to expensive medical interventions, such as kidney dialysis or transplants.” In this country, those Americans covered by Medicaid and CHIP (federal insurance for poor children) have far less access to doctors, especially specialists.

Also, the $500 billion in supposed savings from single-payer healthcare, which is mainly presumed to come from eliminating insurance administrative costs, is likely enormously overstated: According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the entire overhead cost for private health insurance — including administrative costs, executive pay, and profits — in 2014 was $194.6 billion, nowhere near $500 billion.

While some of the claims made by Physicians for a National Health Program are undoubtedly true, the good does not seem to outweigh the bad. By way of comparison, while individuals would no longer become medical-induced paupers, it is very likely that the country as a whole would go bankrupt under the plan, subjecting Americans to suffering such as this country has never before seen.

Goodman relates:

In 2009, the Social Security and Medicare Trustees calculated the unfunded liability in the two programs at $107 trillion — a figure about six-and-a-half times the size of the entire U.S. economy.... For both Social Security and Medicare to be financially secure, we need $107 trillion in the bank right now, earning interest, and it’s not there.

And without even taking the step of adding all privately insured and uninsured Americans to the government payroll, the country’s two primary government-funded health systems Medicare and Medicaid are already set to bankrupt the country:

According to the Congressional Budget Office, if Medicare and Medicaid spending continue to grow at their historical growth rates relative to national income, healthcare spending will consume nearly the entire federal budget by midcentury.

Of course, the country would go bankrupt long before we got to that point — meaning that the federal government would not nearly take in enough in taxes to pay its bills, and the government would be forced to resort to printing vast quantities of money to fund its services, causing hyperinflation.

What does that mean in layman’s terms? In Venezuela right now, a country that has some of the world’s largest oil reserves and other natural resources, its unaffordable socialist welfare policies are causing inflation of a mere 1,600 percent, pushing a large proportion of the country to eat out of garbage cans, to move to other countries, and to act on other drastic measures to live, such as giving up their children and committing cannibalism (which reportedly happened in that country’s prisons). When hyperinflation struck in Zimbabwe, the people of the country suffered immensely. As the New York Times quoted one Zimbabwean woman in 2008, “If you’re not fit, you will starve.” Nurses, janitors, garbage collectors, and others just quit showing up for work, devastating public health. In Russia, hyperinflation meant that money that had been enough to buy a condo soon became only enough to buy a pair of boots; the entire country went to a bartering system; and the population crashed from murders and untreated illness and injuries. Do we really want Americans to have to experience such devastation?

Goodman reports that European countries’ healthcare plans as a group are on the same unsustainable paths as ours.

Despite the promises of ample money for everything medical under Medicare for All, the truth is that those promises are little more than wishes, and we need to reduce medical spending, not keep it on its present course.

And no promised cuts or supposed savings from Medicare for All are going to save the system because they aren’t going to happen to any great extent.

Single-payer Savings

Physicians for a National Health Program said that it projects spending savings to come from three sources:

One, we spend two to three times as much as they [single-payer countries] do on administration. Two, we have much more excess capacity of expensive technology than they do (more CT scanners, more MRI scanners, and surgery suites). Three, we pay higher prices for services.

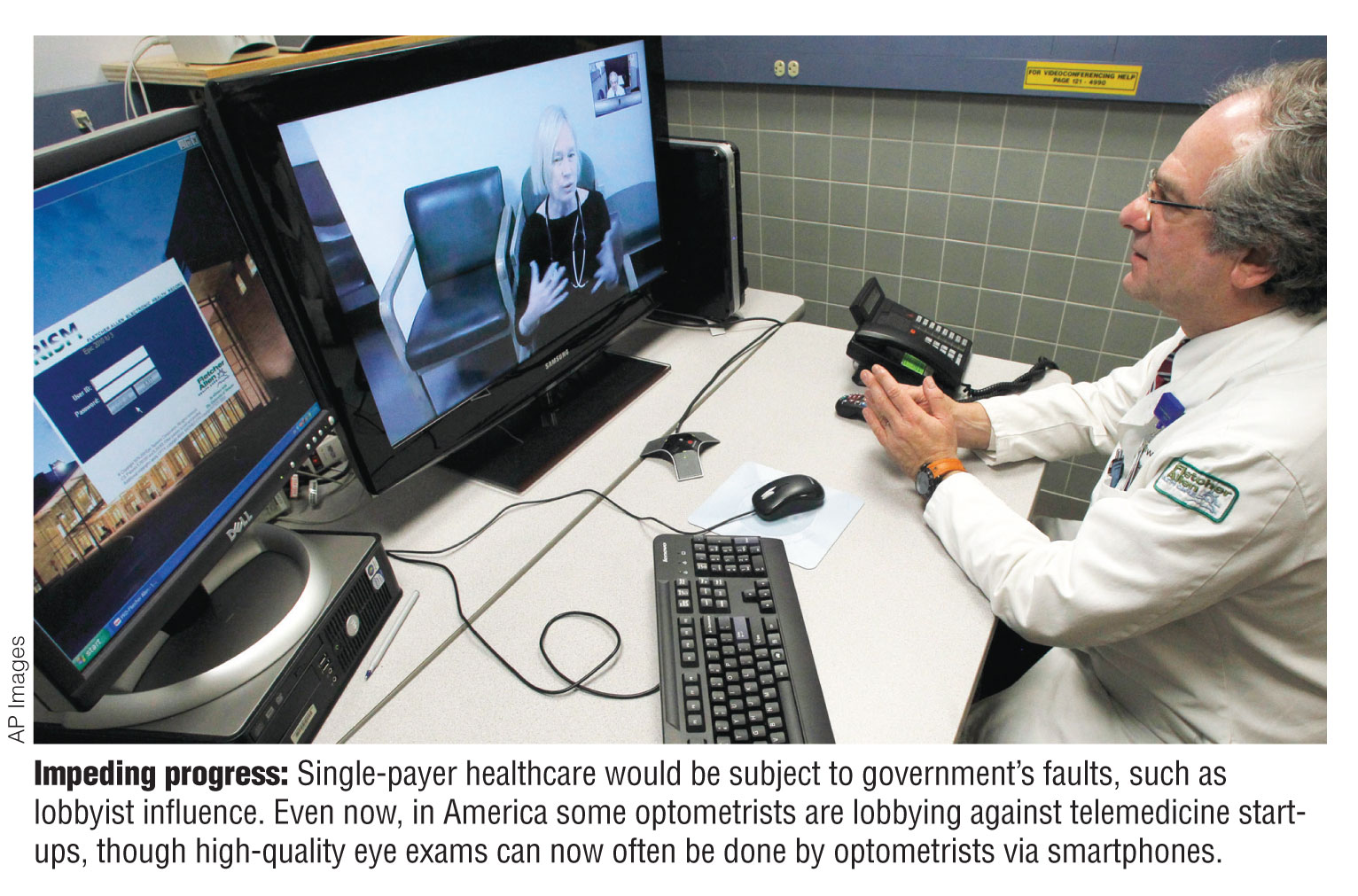

Reality says that these suggested cost savings would prove illusory. As to administrative costs — mainly costs paid by doctors and hospitals to process bills to private insurers — it is reportedly true that administrative costs tend to be much higher to bill private insurance than Medicare. That price difference is largely because private health insurers often require pre-authorization before doctors are allowed to treat patients — authorization doctors have to spend time convincing insurers to allow, according to Dr. David Belk, who runs the True Cost of Health Care website.

But in Medicare-sponsored plans, as in private insurance plans, preauthorizations are a trend and will continue to be a trend, for several reasons:

• For each $10 of Medicare spending, one dollar is believed to be lost to fraud;

• Demand for care for the elderly is so great, and growing, that such measures will be used in response in the hopes of cutting costs.

• As doctors increasingly leave private practices and join medical groups (because of federal legislation pushing them to do so), any additional testing or treatment a patient receives after seeing a primary care doctor will have to be screened so that the government is assured that testing referrals are absolutely necessary and are for the benefit of the patient, not the benefit of the doctors group, thereby stopping unnecessary treatment.

So preauthorizations aren’t likely to go anywhere but up under Medicare.

In fact, under Medicare for All, because “free care” will incentivize all Americans to visit doctors every time they have a concern (as happened in Massachusetts, and is just a natural human reaction to “free stuff”), the only ways that government would be able to avoid spending its resources into oblivion via medical payments would be to ration care through severely limiting the availability of doctors, equipment, or money, or through having protocols in place that require obtaining preauthorization to treat with drugs or devices and limiting the options available to doctors in the way of testing and treatment. And there goes the “quality of care.”

Simply put, to cut costs, either prior authorization often will be required, or items will simply be unavailable. In a similar scenario, the National Health Service in England has announced that, to save money, beginning in April 2017, any drug that costs the NHS more than about $25 million a year will either not be approved at all, or access to the drug will be severely restricted.

Also, claims by proponents of Medicare for All that administrative costs will fall appreciably with the removal of private health insurers because there will no longer be executive payments and profits is undoubtedly wrong. Medicare, which is touted as being better because it is governmental, is run presently mainly by private insurance companies. If we would see government workers actually running Medicare for All, it must be remembered that federal government workers in this country with a high-school education or some college get paid on average 10 percent more than their private-sector counterparts, according to the Congressional Budget Office, and such a system would require a lot of workers. So much for savings there.

Reducing administrative costs would be especially problematic nowadays because at present, according to Roger M. Battistella, a professor in the Sloan Graduate Program in Health Administration and Policy at Cornell University, medicine is now less about treating “acute conditions” that have a dramatic onset and are treated by a single doctor than it is about treating chronic conditions, which don’t lend themselves well to check-list medicine and are “best treated with multidisciplinary, multiprofessional health care teams.” Moreover, the best treatments for such conditions as back pain, breast cancer, and prostate cancer are not only often uncertain, but they require buy-in from patients, without which short-term savings will get eaten by long-term repercussions.

Notably, using checklist medicine and having a lack of face-to-face time with doctors will likely mean a lack of patient buy-in for treatments, and that lack of buy-in will be costly. Battistella says in his 2010 book Healthcare Turning Point: Why Single Payer Won’t Work,

Noncompliance is a big problem, particularly in connection with the treatment of chronic illness. Half of patients fail to follow physicians’ instruction or take medicine as prescribed. Failure to do so results in nearly one-quarter of all nursing home admissions, one-tenth of hospital admissions, and countless extra office visits, tests, and procedures. Noncompliance among cardiac patients is said to cause 125,000 annual deaths (Vermiere et al. 2001; Landro 2005; D9; Orszag 2008). Quality of care and favorable outcomes is a shared physician-patient responsibility. Without the patient’s cooperation, the best treatment can go wrong.... Shared decision making can also help save money. When the choices available to patients are made clear, they tend to prefer less invasive and less expensive treatments than they otherwise would.

Battistella is a strong proponent of government involvement in healthcare; however, he provides evidence that any hope of implementing single-payer healthcare in the United States has long passed. He points out that along with the dire financial situation of the country, the aging of the population makes single-payer untenable, as does the fact that medicines and treatments can now save and prolong the lives of those with chronic illness but only through expensive, recurring treatments. And he’s evidently correct.

The Ouch of Old People

Medicare for All claims that the country will continue spending exactly what the country now spends on healthcare, and that amount will be enough to cover all care, including the burgeoning costs of the elderly as baby boomers retire at a rate of approximately 10,000 per day. Physicians for a National Health Program — in complete contradiction with the Congressional Budget Office — claims that an increasing elderly population will not unduly raise healthcare costs and that they know this because Europe and Japan are aging faster than we are, and their healthcare costs are not exploding: “Studies show that aging of the population accounts for only a small fraction of the increases in health costs.... Germany and Japan recently adopted single-payer long-term care systems to cover the long-term care of the elderly at home and in specialized housing.”

But we shouldn’t believe it because the Europeans certainly don’t. In the 1990s, most of the U.K. officially instituted what was called the Liverpool Care Pathway, which was supposed to ease the passing of those in their last hours of life by providing pain relief. However, scandal broke out when a few doctors became whistleblowers, telling how doctors would not only quickly deem elderly patients to be in their last hours — despite the fact that with treatment, many of the elderly could live substantially longer — but how the doctors would not tell the patients’ families that their loved ones had been put on strong sedatives and not given hydration or nutrition, killing them. Since a nationwide uproar took place when news of it became public, the Pathway was officially disavowed, but critics say that it continues today, just without the name. The fact that the NHS gave financial incentives to use the Pathway indicates the purpose was to save money on treating the elderly.

Additionally, according to a 2012 Guardian article entitled “Germany ‘exporting’ old and sick to foreign care homes,” in Germany, “Growing numbers of elderly and sick Germans are being sent overseas for long-term care in retirement and rehabilitation centres because of rising costs and falling standards in Germany.”

Traditionally, in Germany, families took care of elderly relatives in their homes because of the high expense of institutions; then in 1996, the state began providing long-term care insurance, and families could use the monies provided to either pay for institutionalized care or keep the money and care for the elderly at home. At the time the Guardian article was written, because pension payments did not allow one to afford most retirement facilities — even though the homes were increasingly dirty and manned by Eastern Europeans who spent little time with patients — more than 10,000 German pensioners were in retirement homes in Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, with an unknown number in countries such as Spain, Greece, Ukraine, Thailand, and the Philippines.

According to the online article “How Many Seniors Really End Up in Nursing Homes?” America contains about 78 million baby boomers, and five percent of Americans 65-plus need a nursing home at any given time, with an average stay of six months. As well, 11 million baby boomers will be expected to have two to three chronic health conditions to the extent that they need some type of assistance, such as meals, housekeeping, medicine monitoring, or bathing.

The Family Caregiver Alliance said that in 2007 almost four percent of the total U.S. population needed long-term care — 63 percent of whom were aged 65 or older, and 37 percent under 65. That organization wrote, “In 2012, total spending (public, out-of-pocket and other private spending) for long-term care was $219.9 billion, or 9.3% of all U.S. personal health care spending. This is projected to increase to $346 billion in 2040.”

And those dire figures just mentioned would be before granting the promised long-term care payments to anyone who takes care of the elderly. One out of every five households cares for someone 18 or older. As the Family Caregiver Alliance stated, “Even among the most severely disabled older persons living in the community, about two-thirds rely solely on family members and other informal help, often resulting in great strain for the family caregivers.” If we make this care free, we can expect costs to ascend sharply as families attempt to ease their personal burdens and hire professional care workers.

It’s apparent that the proposed big savings forecast by single-payer advocates will disappear fairly quickly.

As for the savings from granting government the power to allocate where new healthcare equipment will be placed (if too much healthcare equipment really is a problem), it’s not a problem that would go away anytime soon — unless government literally took unto itself the power to tear out existing equipment and destroy much of it.

Of our criteria for an ideal healthcare plan, Medicare for All would likely mean that individuals would not go broke from medical costs. It will have portability and — if you’re fairly old — last a lifetime. It wouldn’t promote much in the way of cost savings, and any savings it might generate would quickly get eaten up by the elderly. At the same time, it would ensure the bankruptcy of the country, yet not mean equitable healthcare for all or high levels of quality care.

If Medicare for All were enacted, the only way it would not bankrupt the country is if healthcare was severely rationed for the oldest and the sickest — essentially meaning the euthanizing of anyone who required costly care — leading to many millions of premature deaths. All told, it’s not a plan that the country can live with.

The trillion-dollar question becomes, “Is there a way Americans can meet our healthcare needs without bankrupting individuals or the country?” The answer to that question is a solid, “It depends.” It depends on the federal government, state governments, doctors, hospitals, and insurance companies.In the next article, we’ll examine allowing free market participants to find ways to meet our criteria for care.