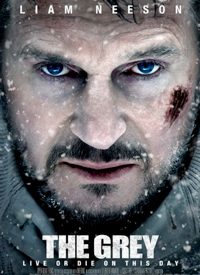

Ottway (Liam Neeson) is an oilman in the Arctic who has grown weary of his job in the frozen north. He wants to be back home with his wife, to whom the audience is introduced through flashbacks. He decides to fly home, but the plane transporting him and his fellow workers crashes, leaving just Ottway and three other survivors in the wilderness to contend with the harsh elements and the vicious wolves.

The men are scarcely acquaintances before the trip began, but, given the situation wherein they find themselves, they must bond quickly in order to ensure their survival. The film focuses on the fluctuating relationships between these men, as there are often shifts between friendliness and animosity amongst them.

What is amazing is the way the men begin to look out for each other, and encourage one another when all seems lost, under the apt leadership of Ottway.

But in addition to how the film examines the changing relationship of the men, it poignantly captures the slowly declining mental states they experience as they struggle to contend with hunger and the fierce weather.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the movie, however, is the presence of Christian elements. One of the survivors is a faithful Christian, who ponders how the ordeal of the four men fits into God’s grand plan. This man’s presence makes for some drama, as another survivor is an atheist who finds the notion of a Higher Being laughable. Ottway finds himself somewhere in the middle, respectful of the faith of others but himself torn by doubt.

Man’s relationship with God plays a significant role in this film, somewhat forming the basis for its central focus. When placed in a difficult situation, can we maintain our civilized selves, our humanity, our better nature, or do we stoop to our basest instincts?

Likewise, all four men are fully aware that their situation is dire and that they will not likely make it out alive, and that reality forces God and the notion of an afterlife to the forefront of their minds and their conversations.

And Ottway, whose own faith journey has been derailed, leaving him with a sense of helplessness and longing, is hoping beyond hope that he can see some sort of sign that erases his doubt.

Slowly, each of the men fights his own battle with death in the wilderness, and Ottway’s confrontation with an alpha wolf in a fight to the end is especially riveting.

A positive element of the film is the overt and explicit references to Christ and His sacrifice on the cross. There is a great deal of prayer in the film, as well as displays of faith.

But there are moments in the film when it seems as if faith is fictional and that total self-reliance is the better choice. There is an irony in the film that underscores that very point. After all, the men view their survival in the crash as some sort of miracle, only to die some other violent or painful way later in the film. Yet, the extra time they have gives them an opportunity to prepare themselves spiritually for the afterlife.

But having such an opportunity is one thing, while recognizing and taking advantage of it is something else. A tragedy which causes one person to move closer to God could cause another to move in the opposite direction. Thus, it could be argued that the presence of doubt adds realism to the film, since even faithful Christians may experience doubt, raise questions about God’s plan, or ponder why bad things happen to good people.

The death scenes in the film are extremely powerful, as those who die are guided by a previously deceased loved one into the afterlife. The scenes involving the wolves effectively capture the ferocity and the raw animalistic nature of the beasts, and underscore how dramatic cinematography can successfully capture gore and fear without obnoxious or unbelievable and expensive special effects.

Overall, the film is a wonderful analysis of human nature and man’s spiritual journey. It will captivate audience’s attention from beginning to end. But what is so positive in the film is unfortunately undermined by the continuous use of foul language.