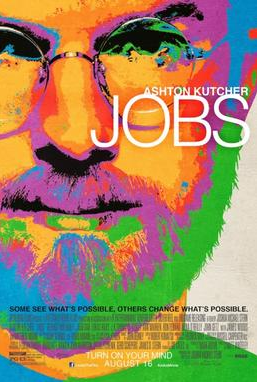

When Apple founder Steve Jobs passed away nearly two years ago, it seemed inevitable that a film honoring the technological and business genius would come out of Hollywood. Jobs, starring Ashton Kutcher as the young Steve Jobs, proves to be an interesting film with some positive elements including a pro-capitalist perspective.

Steve Jobs was somewhat of a mystical man to the public, and the film helps to contribute to the man’s mystique. It tells the story of Jobs’ life from when he started Apple to when he returned to the struggling Apple company, 10 years after its board of directors had fired him. It details how he helped to turn the company around and immortalize himself as a legend. The film spans 30 years, from 1971 to 2001 and attempts to provide an emotional perspective to a story about a technological empire.

Steve Jobs was a college dropout who experienced many of the same struggles as most other young people: confusion about his future and a desire to discover his purpose. He found himself in a delicate and vulnerable place that allowed external influences to distract him. In the film, we see Steve make some unwise choices including experimentation with drugs.

Jobs allowed his quest for self-discovery to take him to India, but the best he could find was a job working for a difficult video game maker.

But Jobs had an eye for greatness, and when his friend Steve Wozniak (Josh Gad) showed him a new computer board, Steve recognized its potential. Together, Jobs and Wozniak built and sold those computer boards, and called their tiny company “Apple.” And when they found an investor to help back the startup company, everything seemed to fall right into place.

Just a few years later, Apple launched the highly successful Apple II personal computer, propelling Apple into a whole new class of businesses, a multi-million dollar one.

Unfortunately, Jobs discovers that all that glitters is not gold. Though at this point he did not have to fear financial problems, he faced an entirely new set of problems that accompanies success, particularly difficult board members who viewed him as an impediment to the company as a result of his obsession with perfection and his eccentricities. In fact, these personality traits hurt Jobs’ personal relationships as well. The board, focused only on money, decides to oust the company’s creator.

Not one to give up in the face of adversity, Jobs creates a new computer company called NeXT. Meanwhile, without Jobs Apple begins to fail.

During his time away from Apple, Jobs manages to gain some control over his emotions and is in a stable marriage. His stability gives the Apple board the security they need to feel comfortable enough to bring Jobs back. They offer him a position as an interim CEO.

It is after Jobs’ return that Apple really takes off.

Interestingly, this is ultimately where the movie ends, a conscious decision of the film’s director, Joshua Michael Stern, who said that he “wanted to end the story where his story really begins.” For Stern, the film is “a prehistory of the Mac.”

While Jobs is an entertaining film, its effort to squeeze 30 years of history into a two-hour film might have been a bit too ambitious. As a result, it sort of oversimplifies the complexities of the man who was Steve Jobs.

Those who fancy themselves well versed on the history of Apple and the biographical history of Steve Jobs have noted that the film is not entirely accurate and that key elements are missing, but much of this is a result of the film’s effort to compress a lot of history into two hours. Therefore, significant storylines such as Jobs’ relationship with the Xerox Corporation and with Pixar are not found in this film, much to the chagrin of some moviegoers.

The director shied away from some of the more tech-heavy elements of the Jobs-Apple story because he wanted the film to focus more on the man behind Apple than the technology. Yet, ironically, the film’s portrayal of the man is lacking. Jobs garnered a reputation for being passionate and eccentric and for struggling with demons, but these characteristics of the man translate poorly on screen. And Jobs’ relationship with his out-of-wedlock daughter, whom he initially denied was his child, does not carry the emotional weight that they should.

There is very little in the way of spiritual elements in the film. Even though Jobs had become a Buddhist, the film only hints at that aspect of his life.

But the film does exude some important moral lessons. Steve’s failure to balance his work life with his family life takes its toll, and the film seems to come down hard on the notion of putting work ahead of all other things.

There is also a pro-life sentiment in the film, though whether or not this was intended is difficult to ascertain. After Steve Jobs was born, he was put up for adoption, and the film depicts him struggling to accept that part of his life. At one point in the film, Jobs opines, “Who has a baby and throws it away like it’s nothing?”

The amazing thing about the film and its subject is the extent to which the real-life biography ensures the film’s inspiring nature. To see what a college dropout can accomplish with just ingenuity and drive is certainly inspirational — and the film does not disappoint in this regard.

Of course, Steve Jobs was not perfect, and those aspects of the Apple genius are present in the film as well, so viewers should watch the film with caution. It is not appropriate for children, since there is a heavy presence of foul language, and there is also some drug use and sexual innuendo.