A Congressional Medal of Honor recipient could understandably be designated a “hero” — but what about those who served honorably in combat in a time of conflict? What about everyone who has served in the armed forces, or in dangerous public vocations such as law enforcement?

Christopher P. Jones’ recent book, New Heroes in Antiquity — from Achilles to Antinoos, may not resolve modern disagreements over the designation, but it does offer insights into the usage of the term by those who coined it. Jones, a professor of classics and history at Harvard, returns throughout his brief work to a common theme: From the perception of classical antiquity, the ranks of the “heroes” are thin, indeed. Jones traces the restricted use of the term “hero” to Homer.

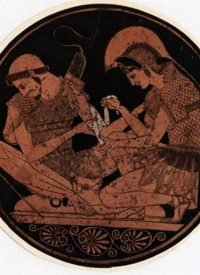

Homer’s use of the word “hero,” and his application of it above all to warriors who fight and often die, was decisive for later generations. He and his near contemporary Hesiod helped to shape all later thought about the divine order; these two, said Herodotus, “first taught the Greeks the descent of the gods (theogoni), and gave to all their several names.”

Beginning from the literary heights of Homer, Jones analyzes the way in which the concept of the “hero” developed over the course of centuries, and in a wide variety of localities, noting two “streams” that led to the designation of new heroes:

I will begin by tracing the two main streams that feed into the creation of such “new heroes” as Brasidas: first, the commemoration of heroes in high poetry and, second, the worship of the petty divinities or “heroes” of particular localities. These two streams meet in the conversion into heroes of those who have fallen in war, or given their lives in the service of their communities in other ways.

For pagan antiquity, the designation of “hero” was clearly linked to a special status after death. Thus, for example, the carved

hero-reliefs that commemorated regional heroes in Thrace proclaimed their elevated role in the afterlife: “In these reliefs, ‘hero’ is not a ‘meaningless compliment,’ but suggests an existence or influence in the afterlife, as the texts that accompany them tell the same tale.” So, too, the speeches commemorating dead “heroes” proclaimed such a privileged status:

These later speeches share several themes. One is the perceived continuity between the legendary heroes and the newly dead. Several of the speakers adduce precedents for Athenian valor from the legendary past, such as Erechtheus in the war with Eleusis and the Athenians’ protection of the descendants of Heracles. Yet while these orators extol the happy lot of the fallen in the next world, their superior status, and their resemblance to the ancient heroes, they refrain from calling them by that name (though the word is sometimes introduced by modern translators).

The determination that someone was a “hero” did not mean that they were merely culturally significant — they were protectors of their society during life, and were believed to have been awarded a special place after death. Thus, despite the ongoing significance of the Greek philosophers for the development of Western thought, they were not perceived to be “heroic”:

In general, it is remarkable how little evidence there is for the philosophers of the archaic period receiving veneration as heroes: at most they seem to receive a cult that places them on a higher level than the ordinary dead, but not with warriors and statesmen such as Brasidas and Timoleon.

What a marked contrast to those bluster of policy wonks and chicken hawks who loom large in their own imaginations! Such persons often have, it would seem, little awareness of the cost in suffering, and acts of profound bravery, which idle political decision of an hour exact from an entire generation of the rank and file serving in a nation’s armed forces.

Jones observes that the rise of Christianity brought an end to earlier notions of “heroism” because of the pagan notion that had been implicit in the use of the term in antiquity. Although some have pressed what Jones refers to as an “extreme form” of an argument for continuity between the pagan notion of the “hero” and the Christian recognition of “saints,” Jones takes a much more limited view.

The only heroes that truly survived the advent of Christianity are the earliest ones of Greek literature, especially those of the Homeric poems. The anxieties of early Christianity were fixed on the pagan gods, not on the heroes.

In Jones’ estimation, the ancient heroes thus continued to enjoy a place within a Christian worldview:

Christian thinkers admired Achilles, Hector, and others like them without making them imaginary beings who had never lived in the real world. They did not turn them into Christians before Christianity, as they sometimes did with Socrates, Virgil, or Seneca. Instead they found a way to accept their exceptional status without compromising their belief that only one person had truly combined the human and the divine, that only He was the Son of God and not one of several sons of God.

Jones also observes that any notion of “living heroes” was restricted to the absolute barest of exceptions to a rule that to be a “hero” was to be numbered among the revered dead of pagan antiquity. What the Greeks and Romans would have thought of modernity’s flippant use of one of its highest honorifics is readily apparent.

Christopher P. Jones, New Heroes in Antiquity — From Achilles to Antinoos (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2010), hardcover, 123 page, $29.95