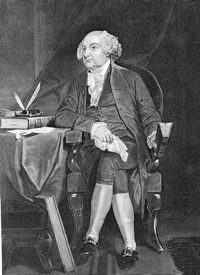

Whatever the merits of such claims, on occasion a volume — or two — of lasting significance emerges in this category of political discourse, and readers have been so blessed with the recent release of the two-volume edition of John Adams’ Revolutionary Writings, published by The Library of America.

The modern publication of the writings of John Adams would hardly seem in need of apologia. From his central role in the Continental Congress, through his ambassadorial service representing his nation in Europe, to his terms both as vice president and then President of the United States, Adams’ pivotal role in the early days of this nation should always recommend a careful study of his writings. That Adams was also a careful student of law and political philosophy adds further enduring value to the continued inquiry into his thought. In fact, the late scholar of history of conservative thought, Russell Kirk, deemed Adams to be “the founder of true conservatism in America,” and devoted the third chapter of The Conservative Mind to a careful analysis of the nation’s second President as a vital link in a succession of conservative thinkers extending from Edmund Burke to our own age.

The Library of America edition of Adams’ Revolutionary Writings is divided between a volume of his earlier labors, from 1755–1775, concluding with his “Novanglus” essays, and a second volume encompassing the revolutionary period from 1775 through 1783, concluding with the peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States, which Adams helped draft.

The two volumes were edited by Gordon Wood, a distinguished historian of the early Republic and professor emeritus of Brown University, whose recent works include Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different. In fact, his chapter on John Adams in that volume in certain regards anticipates the portrait of the patriot presented in the pages of Revolutionary Writings. Wood has provided extensive notes on the texts, but a notable feature of Revolutionary Writings is the absence of introductory material; one is simply brought to the chronologically arranged compilation of essays, letters, diary entries, etc., and allowed to find one’s own way; even Wood’s notes are consigned to the end of the volume. One result of this arrangement is that the novice may find the bare text somewhat daunting, but such readers can easily utilize the detailed chronology at the end of the volumes to provide a measure of context. Personally, this reviewer found it pleasant to encounter an editor who does not insist on telling the reader how he should interpret a text before actually allowing him to read it.

Since several efforts have been undertaken previously to publish anthologies of John Adams’ various political writings, it is worth noting Wood’s contribution to this effort in this context. The three most noteworthy recent efforts in this field are the volumes by George A. Peek (originally published in 1954) and George Carey (2000), both of which were entitled, The Political Writings of John Adams, and C. Bradley Thompson’s The Revolutionary Writings of John Adams (2001). Of these two collections, Carey’s is manifestly superior, offering a greater range of Adams’ writings, and including works that fall outside the purview of Wood’s Revolutionary Writings. However, Thompson’s Revolutionary Writings appears to have been superseded by Wood’s two volumes — not on account of any deficiency in Thompson’s edition, but simply because of the greater extent of material available in the new volumes.

There is, of course, a degree of repetition in terms of the contents of the Wood and Carey compilations. For example, both editions include Adams’ Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law (1765) and his series of “Novanglus” essays (1775). However, as regards the latter work, the new edition is to be preferred, since it also includes the complete text of the essays of David Leonard (“Massachusettensis”), which were the catalyst for Adams’ “Novanglus” essays.

Undeniably, there are aspects of the Carey volume that continue to recommend it. Carey’s volume is a collection of the “political writings” — and not only “revolutionary writings” — of Adams, and thus, for example, it includes an abridged version of A Defence of the Constitutions of the United States of America (1786–87), as well as The Report of a Constitution, or Form of Government, for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1780), and 1797 Inaugural Speech. In short, the diligent inquirer into the thought of John Adams will find both Carey’s and Wood’s collections to be worthy additions to his library.

As noted previously, no extended defense is required for the reasons for reading Adams — especially at a time when the most fundamental principles of constitutional conservatism are being challenged on all sides. The daunting size of the two volumes belies the nature of their contents: Much of what is collected in this work consists of letters and essays that are quite brief, and allow the reader to delve into Adams’ thought a few pages at a time. The immediate value of the various entries is admittedly uneven; but an astute reader will find much "food for thought." Some of the works such as A Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law (1765), the “Novanglus” essays (1775), Thoughts on Government (1776), Letters from a Distinguished American (1780) — even little treasures such as Adams’ letter to his son, John Quincy, on the merits of studying Thucydides (August 11, 1777) — are of lasting benefit to those who admire the genius of the age of the American Founders, and especially that of that remarkable founder of American Conservatism, John Adams.

John Adams, Revolutionary Writings, 1755–1775/1775–1783, 2 volumes, (New York: The Library of America, 2011). 743 pages and 811 pages, respectively.