Bradley J. Birzer, In Defense of Andrew Jackson, Washington: Regnery History, 2018), 209 pages. Hardcover. $26.99.

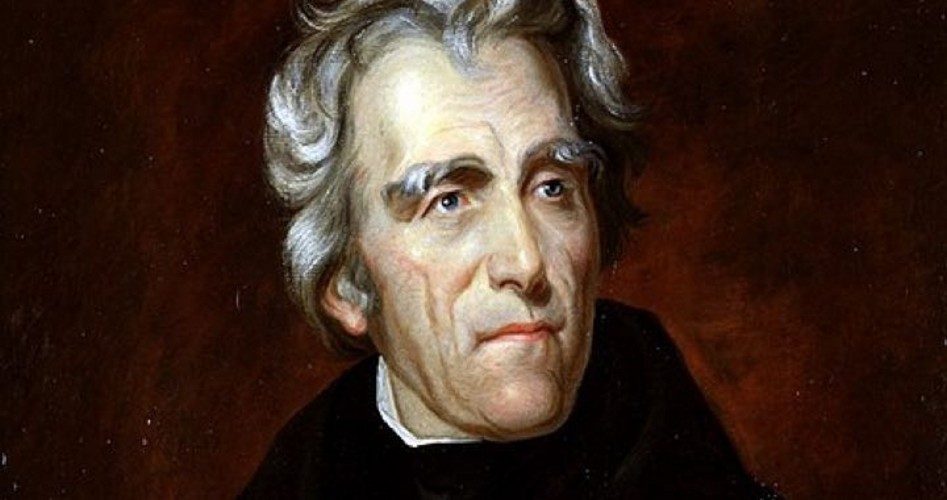

In recent years, the American people have endured the desecration not only of the monuments to, but also the memories of, some of the greatest leaders in our nation’s history. The hipster Jacobins of Antifa have targeted the monuments that commemorate men such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. However, few figures in American history generate animus to such a degree as that which is directed toward Andrew Jackson (1767-1845).

The historical illiteracy of Jackson’s detractors is such that those who rioted in Jackson Square in New Orleans in 2017 demanded that the city “remove the names and statues honoring the treasonous Confederates and white supremacists, who tried to overthrow the U.S. government and killed hundreds of thousands of Americans to preserve slavery for their own economic gain.” In March 2018, rioters had not grown any more aware of actual American history, and thus their renewed protest at Jackson Square — a square which commemorates Jackson’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812 — was explained by a spokesman as “continuing our protest, to show people and explain to people that these things are offensive to black people especially, and should be offensive to democratically minded people.” Of course, when he was elected to the presidency, Jackson received nearly five times the electoral college votes of his opponent, Henry Clay, and received 56 percent of the popular vote.

In response to such historical illiteracy, Dr. Bradley Birzer of Hillsdale College has written a brief overview of the life and presidency of our nation’s seventh president: In Defense of Andrew Jackson. Although he has taught courses for decades on the “Jacksonian period of American history,” Birzer was worried that Jackson’s world was “irreversibly removed from anything within my immediate experience.” However, as he began his research, Birzer found that his subject overcame any such concerns. He stated:

In the end, Jackson made bridging the gap between our worlds easy because whatever his faults — and there were many — he was nothing if not brutally honest about himself and his ideas. Endowed with a nearly supernatural will power and a conviction that could move mountains, Jackson considered it a virtue to be as consistent as possible, even in his violence. Throughout my research, I found evidence of his impressive dedication to his virtue, especially when examining Jackson’s reeling in love, life, and his beliefs.

In Defense of Andrew Jackson is a brief introduction to the life of “Old Hickory” (a nickname that soldiers under his command gave him during the War of 1812). Birzer relies heavily on Jackson’s own writings to flesh out his narrative. This is not a dense, academic text; rather, it is an engaging, sympathetic overview that encourages readers to continue to learn more about its subject. As Birzer explains, “Jackson might be unpopular now, but his continued significance, including as a hero to the current president of the United States, is exactly what this book hopes to explain.… The more I have studied Andrew Jackson, the more I have come to respect him. Forced to rank the U.S. presidents in terms of character, honesty, and effectiveness (regardless of political positions), I would rank him number four, after Washington, Lincoln, and Reagan, respectively.”

Jackson’s commitment to the Republic; his preference for militias in the defense of that Republic over reliance on a standing army; his devotion to “his Sovereign, the People”; his dedication as president to uphold the Constitution of the United States; and his tireless campaign against monied interests that he saw as waging war against the liberties of a free people are themes that unite the life of Andrew Jackson and the text of In Defense of Andrew Jackson. Birzer’s inclusion of Jackson’s “Farewell Address” to the book (roughly one-sixth of the overall text) is a capstone that gathers these themes, as Jackson wrote to the people of the United States in March, 1837:

You have no longer any cause to fear danger from abroad; your strength and power are well known throughout the civilized world, as well as the high and gallant bearings of your sons. It is from within, among yourselves — from cupidity, from corruption, from disappointed ambition and inordinate thirst for power — that factions will be formed and liberty endangered. It is against such designs, whatever disguise the actors may assume, that you have especially to guard yourselves.

Photo: senate.gov