Nullification: How to Resist Federal Tyranny in the 21st Century by Thomas E. Woods, Jr., Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing Inc., 2010, 309 pages, hardcover.

Nullification is an indispensable book about what could become the most effective means of stopping an out-of-control federal government: nullification. "Nullification" is simply an act by states (and occasionally individuals) to resist unconstitutional federal laws. The term “nullification” was coined by Thomas Jefferson in his 1799 Kentucky Resolutions that protested the Alien and Sedition Acts’ unconstitutional criminal ban on criticism of the President. (The ban violated the First, Ninth, and 10th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution). Loaded with primary sources among the more than 100 pages of appendices, Thomas Woods’ Nullification should become an action manual for committed activists of the Tea Party movement on the issue of federal healthcare mandates and a host of other issues.

Woods begins his must-read book by exploding one of the three main arguments usually levied against state nullification of unconstitutional federal laws: There’s nothing in the Constitution about nullification. The three basic arguments against nullification are: 1. It’s unconstitutional, 2. It doesn’t work, and 3. It is nothing more than a tool of racists or secessionists who want another civil war. Woods proves definitively that none of these arguments have the slightest merit. He is quick to point out in Nullification the irony of the first objection to nullification: Most of the politicians who pushed the healthcare law (and are presumed to be nullification opponents) don’t care in the slightest about the U.S. Constitution anyway.

The author explains the constitutional justification for nullification of unconstitutional laws: the 10th Amendment. Indeed, nowhere in

the Constitution is any branch of the the federal government given the exclusive right to “interpret” the document. (Yes, it sounds silly to speak about needing an “interpreter” to read a document written in straightforward English prose, but that’s the unfortunate terminology government uses today.) It’s true that the Supreme Court has always acted as if it has the exclusive right to “interpret,” but the supremacy clause in Article VI of the Constitution merely stipulates:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

The supremacy clause simply states that judges must follow the Constitution, not that the Supreme Court is the exclusive judge of what is — or is not — constitutional. Likewise, other branches of government are bound to follow the Constitution. Article 2 specifies the President must swear to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” In fact, if there is an exclusive interpreter of the Constitution, it is the states or the people, since the 10th Amendment stipulates: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

If the exclusive right of interpretation is not expressly delegated to the United States — and indeed it is nowhere found in the text of the Constitution — then that authority clearly resides in the states and the people. The 10th Amendment is key to understanding both the limitations of the federal government as well as the unlimited nature of the response appropriate from the states and the people. The 10th Amendment figures prominently in Nullification.

Woods also exposes the canard that nullification has never been successful, taking this historical fiction out to the factual Woods-shed. The author cites numerous examples of how nullification has worked in the past, and is continually working in the present. For example, the federal Real ID Act of 2005 tried to tell states how to issue drivers’ licenses but has been effectively nullified by the states. Half of the states issued formal declarations that they have no intention of ever complying with the federal mandate and Woods notes that “resistance was so widespread that although the law is still on the books, the federal government has, in effect, given up trying to enforce it.”

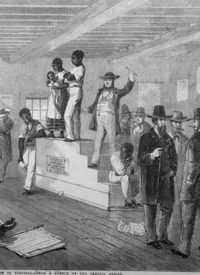

Contrary to claims that nullification is only a tool of racists, nullification of the Fugitive Slave Act from the Compromise of 1850 was also widespread and highly effective, Woods points out. In fact, nearly every state that later seceded (primarily in reaction to Lincoln’s election to the presidency) mentioned it in their resolution of secession. Mississippi complained that Northern state officials “nullified the Fugitive Slave Law in almost every free State in the Union, and has utterly broken the compact which our fathers pledged their faith to maintain.” South Carolina and Texas made almost identical claims, with Georgia complaining in its secession resolution: “For above twenty years the non-slave-holding States generally have wholly refused to deliver up to us persons charged with crimes affecting slave property. [Northern state officials] shield and give sanctuary to all criminals who seek to deprive us of this property or who use it to destroy us. This clause of the Constitution has no other sanction than their good faith; that is withheld from us.”

Woods almost entirely ignores Jim Crow laws in Nullification, perhaps because it is already well known and emphasis upon it could politically detract from popularization of the nullification issue. But he is quick to point out that nullification was employed against racism in nullifying the Fugitive Slave Act decades before racists copied the tactic and nullified the “equal protection” and clause of the 14th Amendment. Both Jim Crow supporters and their civil rights activist rivals used nullification, though civil rights protesters arguably only attempted to nullify state laws.

But Jim Crow laws also revealed that nullification is without a doubt an effective tool. If Jim Crow laws could successfully nullify the 14th Amendment for nearly 100 years, one could hardly call nullification ineffective. Just imagine what success a nullification effort with a good cause could have. Why should only racists be able to use this highly effective tool?

Woods’ book is undoubtedly the definitive work on the subject of nullification currently in print, though it cries out for a sequel with more information and even greater detail. Though he’s written this first trailblazing exposition on nullification, there’s still a lot of ground to cover on the topic.

There are currently two competing definitions of the term “nullification.” Woods chooses the narrower, Jeffersonian definition: “Nullification … involves the refusal to enforce unconstitutional laws, not simply laws the states do not like.” But a competing, wider definition, as exemplified by the pro-nullification Fully Informed Jury Association, claims that nullification encompasses relying upon “personal conscience, to judge the merit of the law and its application, and to nullify bad law.” The difference is simply this: One would nullify only unconstitutional laws — those inferior laws that clearly conflict with the U.S. Constitution — and vindicate the law, while the other would ignore the law completely and decide based upon whatever in his or her personal judgment simply doesn’t like.

Put another way, the more limited Jeffersonian definition seeks to validate the limits of the U.S. Constitution, while the broader definition is an anarchistic attack on all objective law. Woods’ book does not have any detailed discussion of the constitutional merits of laws that were nullified by states throughout American history, even though many instances of nullification in American history were constitutionally dubious.

South Carolina’s nullification protest against the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations” would fall into the latter category. The 1828 tariff law was a terrible law, based upon poor economic theory and vindictive sectional rivalry, but it was clearly a constitutional law. The Constitution allows Congress to pass virtually any indirect tax so long as it is “uniform” throughout the United States, a constitutional requirement that the 1828 law undoubtedly fulfilled.

Likewise, the 1787 Constitution clearly required free states to turn over fugitive slaves to slave-owning states. Northern abolitionists sought to nullify the Constitution itself, albeit to stop a hideous injustice, in opposing the fugitive slave laws (as well as the unconstitutional federalization of those laws after the Compromise of 1850). The same could be said of Jim Crow laws after the Civil War, which tried to nullify the “equal protection of the laws” clause of the 14th Amendment.

These examples stand in stark contrast with Jefferson’s attacks on the anti-free speech provisions of the Alien and Sedition Acts, which undoubtedly fell into the category of an unconstitutional law, or state nullification of the clearly unconstitutional Real ID Act of 2005 and Obama’s more recent healthcare mandate.

The variety of nullification cases throughout American history mean that states have nullified both constitutional and unconstitutional laws, and for both good and evil causes. Was nullification of the Fugitive Slave law acceptable, even though it was constitutional? When should bad law stand and nullification dropped as a tactic? At what point should the conscience choose God’s natural law over the “highest law in the land”? Woods did not take pains to make these distinctions or answer these questions. He leaves the moral questions to his readers to decide, perhaps because taking a clear stand on these controversial questions could defeat the book’s purpose in popularizing nullification as a remedy for out-of-control government.

Nor does Woods delve very deeply into the far broader concept of jury nullification. His book is a survey of the issue, and the best summary of the issue in print, one with copious primary source documents. Thus, he barely mentions jury nullification as a valuable tool: “Although few people realize it, the consensus among the Founding Fathers was that jury nullification was an essential defense mechanism for a free people.”

But jury nullification is even more susceptible to the broader understanding of the term “nullification,” taking it beyond action by state legislatures, something that 5P-anarcholibertarians (The five “P”s are: Pro-abortion, Pimp, Prostitute, Pornographer, or Pothead) are all too eager to realize. Thus, it’s important that this first thorough discussion of nullification was undertaken by Professor Woods, who is by no means a 5P anarcholibertarian. Woods’ Nullification makes an unfair negative stereotyping of the movement by the Left exceedingly difficult, though this stereotyping is something in which many leftists often engage (even while they rail against their opponents for stereotyping).

Nullification is not a review of some ancient and long discarded doctrine of Jefferson, rather it is a cogent analysis of an effective tool continuously at work in American society throughout American history. American history is so thoroughly marinated in nullification that its distinctive pattern is rarely noticed among political analysts. Woods provides the remedy for that short-sightedness and notes that “plenty of people make nice salaries writing think-tank reports, some of them quite good, about the benefits of freedom in this or that area. Isn’t it time to supplement all the report-writing with vigorous, constitutional action in the tradition of Jefferson?”

Yes, it is time. And Professor Woods’ book is a necessary and powerful opening argument for a renewal of that constitutional action.

To order the book, click here.