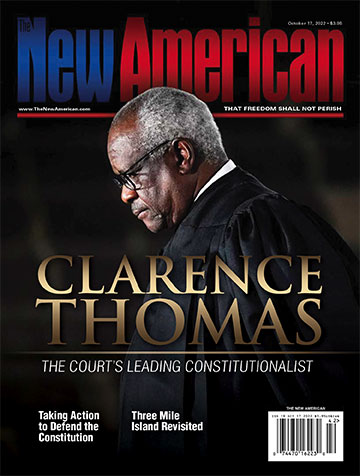

Clarence Thomas: The Court’s Leading Constitutionalist

In May 2000, Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas spoke at a dinner function of the Oklahoma Council on Public Affairs, a conservative think tank. His topic was mostly his judicial philosophy.

Answering questions after the speech, Thomas responded to a query from a state politician who asked, “Isn’t the Constitution a living, changing document?” Thomas answered, “His may be living and breathing, but mine’s inanimate.”

Another person asked Justice Thomas which cases he found the most difficult to decide. “The hard case,” Thomas responded, “is where your heart really wants to do something for somebody and the law says you have no authority. That’s when you see whether or not you are a judge or you’re lawless.”

This philosophy — to follow the Constitution and the law, and not substitute one’s own opinion as to what the law should be — is important to know in order to understand Clarence Thomas’ view of his role as a judge on the highest tribunal in the federal system. After more than three decades on the Supreme Court, Thomas has emerged as arguably the leader of those justices who try to follow the Constitution, as their oath of office requires them to do.

Justice Thomas emphatically rejects the idea that stare decisis (the legal principle of determining points in litigation according to precedent) should dictate decisions in a case before him, if previous court decisions are in conflict with the actual words and meaning of the Constitution. “I think a lot of people,” Thomas explained on a CSPAN program a few years ago, “lack courage, like they know what is right and they are scared to death of doing it and they come up with all of these excuses for not doing it. When someone runs out of arguments, they turn to stare decisis.”

He once said, “When faced with a clash of constitutional principle and a line of unreasoned cases wholly divorced from the text, history, and structure of our founding document, we should not hesitate to resolve the tension in favor of the Constitution’s original meaning.”

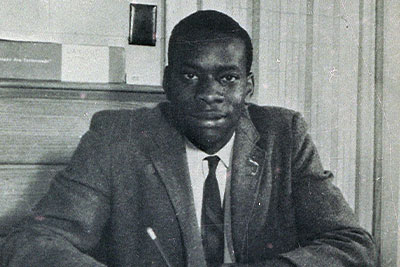

Destined for greatness: Clarence Thomas came from humble circumstances, but even from an early age, he showed much promise. Here he is shown in his role as the co-editor of his high-school yearbook. (AP Images)

While a graduate of Yale Law School, Thomas joked during oral arguments of a case in 2013 that a law degree from either Harvard or Yale might be proof of incompetence. It seems that Thomas did begin to develop his philosophy while at Yale, although not from his professors so much as from his own reading. One author who had great influence on his thinking was Thomas Sowell, an economist, who, like Clarence Thomas, is a black American.

Clarence Thomas was born in Pin Point, Georgia, in impoverished circumstances. His father had abandoned the family, and he, his mother, and sisters went to live with his grandfather, who instilled in him values of hard work, honesty, and moral behavior. From these humble beginnings, Thomas was eventually named the chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) by President Ronald Reagan. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush nominated him for a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court.

For all their talk about giving opportunity to blacks, the Democrats in the Senate were not about to give Thomas an opportunity to serve on the Supreme Court. They grilled him mercilessly, even challenging his view that the natural law principles found in the Declaration of Independence are an interpretive grid for the Constitution. When that did not work, they produced an obscure law professor, Anita Hill, from the University of Oklahoma — who had worked with Thomas at the EEOC years earlier — to claim Thomas had sexually harassed her. Hill was an ardent progressive, and her allegations were forcefully denied by Thomas. Eventually, after a bruising battle, he was confirmed, 52-48.

It appears that Thomas was already much more conservative than President Bush had realized, and Thomas has said that his treatment by the committee and the national media during the confirmation hearings, if anything, hardened his judicial philosophy. At the previously mentioned dinner in Oklahoma, which took place less than a decade after those hearings, Thomas touched on that unhappy episode.

As bad as it was, he told the gathering, which included this writer, he would go through the process again because of his commitment to the Constitution. Others had died defending the document, he explained, so “How could I say that I wouldn’t sustain or endure just minor inconveniences to defend that document and interpret it. I think that would be an act of pure cowardice.”

Thomas Changes the Supreme Court

Because Thomas tended to vote the same as the late Justice Antonin Scalia, many observers have assumed that Scalia had great influence on him, but it was actually the other way around: Thomas often brought Scalia and Samuel Alito over to his thinking on cases. In her book on the Supreme Court, Jan Crawford noted that Thomas also influenced then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Even during the Rehnquist years, Thomas advocated overruling precedents he considered poor interpretations of the Constitution, more so than any other justice.

A look at some of the opinions Thomas wrote confirms that, in his mind, he had taken an oath to the Constitution, not to what some previous Supreme Court had said about it.

An example of a case that is only a federal issue because of the Incorporation Doctrine (the idea that the 14th Amendment applied the restrictions of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, for example, to the states as well as the federal government) was Good News Club v. Milford Central School, a case in which Thomas wrote the majority opinion. At one time, the Incorporation Doctrine was quite controversial, but in the last several decades even some very conservative legal scholars have supported it. The Incorporation Doctrine has led to the transfer of many cases to the federal court system that would — and should — have been left to state courts.

Milford Central School authorized district residents to make use of its facilities after school hours. Two district residents asked to set up a private Christian organization for children known as the Good News Club, but Milford denied their request, arguing that allowing a religious organization to use the facilities would constitute a government establishment of religion. (Again, the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause only restricted Congress from establishing a national religion — states, on the other hand, were free to do so. But with the Incorporation Doctrine, this was considered a case for the federal courts).

The club filed suit, contending that the school district had denied them the right of free speech, considering that other secular clubs could freely use the facilities.

In his majority opinion, Thomas wrote, “Milford’s restriction violates the Club’s free speech rights and that no Establishment Clause concern justifies that violation.… When Milford denied the Good News Club access to the school’s limited public forum on the ground that the Club was religious in nature, it discriminated against the Club because of its religious viewpoint in violation of the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

Another case that landed in the lap of the U.S. Supreme Court, Kelo v. The City of New London, involved the doctrine of eminent domain — the power of a government to take private land. Under the Fifth Amendment, this power is restricted to the taking of land for public use, and only with just compensation. But in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the city of New London, Connecticut, to take a working-class neighborhood, not for a public use such as a government building or a public road, but so the city could give it to the Pfizer Corporation.

The New London City Council believed this would create more economic activity for the city — and more tax revenue — than the private homes that they bulldozed. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court allowed the taking under the reasoning that the taking served a “public purpose.” Thomas dissented, writing, “The deferential standard this Court has adopted for the Public Use Clause [is] deeply perverse.”

Sixteen years later, the Court refused to hear a case that would challenge the precedent set by Kelo — that no public use is necessary, only a public purpose. Thomas condemned the refusal to hear a case that would have challenged the “perverse” Kelo ruling: “The Constitution’s text, the common-law background, and the early practice of eminent domain all indicate ‘that the Takings Clause authorizes the taking of property only if the public has a right to it, not if the public realizes any conceivable benefit from taking. The majority in Kelo strayed from the Constitution to diminish the right to be free from private takings.”

The effect of a refusal to correct Kelo, Thomas said, would “leave in place a legal regime that benefits those citizens with disproportionate influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms.”

Protecting the Second Amendment

The recent case of New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen demonstrates Thomas’ growing influence on his fellow justices — at least on some of them.

In New York, the state government has long had little regard for the right of individual Americans to enjoy their right to keep and bear arms, dating back to the early 20th century and the Sullivan Law.

Under the anti-gun-rights statutes of New York, it was very difficult for a private citizen to legally carry a firearm. Even after the U.S. Supreme Court rulings of District of Columbia v. Heller (which held that the Second Amendment protected the right of individuals to own a firearm in federal districts and territories) and McDonald v. Chicago (which held that states and local governments also must respect the Second Amendment — again using the Incorporation Doctrine), New York attempted to deny average, law-abiding citizens the right to carry handguns publicly.

Thomas wrote the majority opinion in Bruen, arguing, “We … now hold, consistent with Heller and McDonald, that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual’s right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home.” In New York, citizens had to prove to legal authorities that they had some “special need” to carry a weapon outside the home. “Heller and McDonald do not support applying the means-end scrutiny in the Second Amendment context.” Thomas noted that those decisions recognized that the Second Amendment only codified a pre-existing right that did not “depend on service in the militia.”

Thus, New York’s “may issue” granting of a license to carry a firearm outside the home was changed to “shall issue,” as in most other states. In other words, the government must issue such licenses — if they issue licenses at all — unless there is reason not to (such as a felony conviction). Under “may issue,” New York could refuse to issue a license, and it was up to the private citizen to convince the authorities to do otherwise.

One might note that Thomas is not opposed to citing precedent, but only if the precedent conforms to the Constitution. While he cited Heller and McDonald, he opined that they were consistent with a specific portion of the Constitution — the Second Amendment.

Further illustrating the fact that Thomas does not simply issue opinions that conform to his personal standards is his stance on federal marijuana laws. While Thomas does not personally support the use of marijuana, since 2005 he has declared that the federal government regulating marijuana within the borders of a state violates the Constitution, as there is no part of the Constitution that authorizes such regulation. As MSNBC opinion columnist Chris Geidner noted, Thomas’ opinion on this issue is not a pro-legalization statement, but “The reality is far more nuanced — and a part of Thomas’ larger effort to rein in the federal government across the board.”

Thomas said the federal government’s regulation of marijuana “strains basic principles of federalism and conceals traps for the unwary.” As an example, he noted, “Many marijuana-related businesses operate entirely in cash because federal law prohibits certain financial institutions from knowingly accepting deposits from or providing other bank services to businesses that violate federal law.”

Of course, Thomas is right on the Constitution. There is no provision in the U.S. Constitution that grants Congress the power to regulate marijuana purely within the borders of a state. That is why, in 1918, Congress only moved to regulate alcoholic beverages after the passage of the 18th Amendment, which gave Congress the power to do so. Today, when Congress decides to do something, little to no consideration is given to whether there is authorization for it in the Constitution.

Thomas and the Commerce Clause

The Constitution’s “Commerce Clause” — Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 — is often used to argue that the federal government does have the power to regulate drugs and alcohol. Thomas, for his part, believes the Commerce Clause has been stretched far beyond its original meaning so as to justify an expansion of federal powers.

Thomas argues that the Commerce Clause was intended to regulate economic activity across state lines, not activities that might conceivably affect interstate commerce. In United States v. Lopez, the Supreme Court held that the Gun Free Zones Act of 1990, which prohibited “any individual knowingly to possess a firearm at a place” a person knows is a school zone, was a case in which Congress had exceeded its authority under the Commerce Clause. The Court ruled that the possession of a gun in a local school zone is in no sense an economic activity. The majority of the justices contended that what Congress was doing, in trying to use the Commerce Clause to justify the federal prohibition of gun possession in a local school district, was piling inference upon inference in order to justify using the Commerce Clause to take over general police power that is held only by the states.

Thomas concurred with the ruling, but took the opportunity to assert his view that the only thing the Commerce Clause allows Congress to legislate on is actual trade across state lines. He said, “The power to regulate ‘commerce’ can by no means encompass authority over mere gun possession, any more than it empowers the Federal Government to regulate marriage, littering, or cruelty to animals, throughout the 50 states. Our Constitution quite properly leaves such matters to the individual States, notwithstanding these activities’ effects on interstate commerce.”

In Gonzales v. Raich in 2005, which involved California residents who were growing marijuana for their own medical use, the Supreme Court upheld the authority of the federal government to regulate marijuana. Thomas dissented, writing, “If Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate virtually anything — and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers.”

This is an example of Thomas focusing on the real issue: the U.S. government’s twisting of the plain wording of the Constitution in order to increase its powers. Critics have expressed concern that should Thomas’ position ever prevail on the Supreme Court, much of what the federal government does in modern America would be invalidated.

One can only wish.

The federal “war on drugs” has led to perverse abuses of the rights of individual American citizens in the form of Civil Asset Forfeiture (CAF). CAF is a perfect example of how federal law enforcement has exceeded its jurisdiction in a manner that tramples on many other rights. Under CAF, federal agents can seize personal and real property that they allege was somehow used to promote drug trading. A person whose property was thus seized must then prove it was not used in drug dealing. The argument is that the case is not criminal, but rather civil, and the government’s case is against the automobile, yacht, or house that was used in the illicit drug trade.

Sometimes, the “fine” in these CAF cases is the seizure of the property. In the case United States v. Bajakajian, Thomas wrote the majority opinion, which declared an excessive fine unconstitutional. A person was fined for failing to disclose more than $300,000 in his luggage on an international flight. Under CAF, the passenger forfeited the entire amount! Thomas’ opinion was that this was a clear violation of the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause and was “grossly disproportional.”

Because Thomas is black, special notice is often given to his views on issues such as affirmative action — the practice of favoring individuals who belong to a group regarded as having suffered racial discrimination in the past. Among the places that this happens is in employment hiring and promotion, and in college admissions. Thomas opposes this practice, arguing that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment prohibits any consideration of race. In Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, Thomas wrote, “There is a ‘moral [and] constitutional equivalence’ between laws designed to subjugate a race and those that distribute benefits on the basis of race in order to foster some current notion of equality. Government cannot make us equal; it can only recognize, respect and protect us as equal before the law.”

In another affirmative-action case involving education, Thomas concurred with the opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” but then added his own opinion: “If our history has taught us anything, it has taught us to beware of elites bearing racial theories.” He contended that the arguments of those who supported racial discrimination in the name of affirmative action were making remarkably similar arguments about race as did segregationists in the famous case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Substantive Due Process

Perhaps in all of these cases, Thomas’ consistency is found in his desire that Supreme Court justices base their opinions not on what they think law should be, but on what the law actually is. He made this crystal clear in his concurring opinion in this year’s historic Dobbs case, which reversed the Roe v. Wade ruling of 1973. In his concurring opinion, Thomas called the practice of “substantive due process” — when justices substitute their opinions for the law because they believe a law is so terrible and unfair that it should be struck down by judicial fiat — an oxymoron that “lacks any basis in the Constitution.” He added, “The notion that a constitutional provision that guarantees only ‘process’ before a person is deprived of life, liberty, or property could define the substance of those rights strains credulity for even the most casual user of words. The resolution of this case [the Dobbs case] is thus straightforward. Because the Due Process Clause does not secure any substantive rights, it does not secure a right to abortion.”

Thomas added that there were three dangers in continuing to decide cases under the “substantive due process” grid. He contended that it “exalts judges at the expense of the people from whom they derive their authority.… In practice, the Court’s approach for identifying those ‘fundamental’ rights unquestionably involves policy making rather than neutral legal analysis.” This leads judges to nullify state laws “that do not align with the judicially created guarantees.”

He cited the infamous Dred Scott v. Sanford decision of 1857 as an example of substantive due process, in which Chief Justice Roger Taney substituted his opinion on the question of whether the Fugitive Slave Law was constitutional because he wanted to settle the issue of the expansion of slavery into the territories. Incredibly enough, Taney believed the Constitution protected the right of slave owners to take their slaves into other parts of the country, even if the law there actually disallowed slavery, and that use of substantive due process led to “immeasurable human suffering.” Interestingly, the late Justice Antonin Scalia believed the Scott case was the first major example of the idea of substantive due process.

The Left has vociferously opposed the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, implying at times that the Dobbs decision somehow “outlawed” abortion on a national scale. Actually, all the Dobbs decision did was say that abortion was a matter the Constitution leaves to the states under our federal system of government. But what particularly generated angst among those Americans for which the “right” to an abortion is of paramount importance was Thomas’ concurring opinion. Thomas agreed with Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett that Roe was wrongly decided, but disagreed with Alito’s remarks that Dobbs’ reasoning should not be considered applicable to other previous rulings favored by the Left.

Alito wrote, “And to ensure that our decision is not misunderstood or mischaracterized, we emphasize that our decision concerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.”

Constitution first: Clarence Thomas was among the five justices who voted to strike down the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade with the recent Dobbs ruling. Thomas, however, wrote a separate opinion in which he made clear his view that justices should not let adherence to precedent overrule their oath to follow the U.S. Constitution. (AP Images)

He was responding to the concerns raised by the dissenting justices that the Dobbs decision “calls into question” cases such as Griswold, Lawrence, or Obergefell. Griswold was the Supreme Court decision that Connecticut could not ban the use of contraceptives by married couples; Lawrence was the ruling that states could not make homosexual relations illegal; and Obergefell held that states could not deny marriage between same-sex couples.

Thomas wrote in his concurring opinion, “Because the Court properly applies our substantive due process precedents to reject the fabrication of a constitutional right to abortion, and because this case does not present the opportunity to reject substantive due process entirely, I join in the Court’s opinion.”

But he then added, “In future cases, we should follow the text of the Constitution.... Substantive due process conflicts with that textual command and has harmed our country in many ways. Accordingly, we should eliminate it from our jurisprudence at the earliest opportunity.” Thomas invited cases that allow the Court to overturn previous rulings based on substantive due process, and many fear he wants to revisit Griswold, Lawrence,and Obergefell.

People holding such fears either misunderstand Thomas’ position, or they are knowingly mischaracterizing it. He is not demanding that Connecticut, for example, return to the time when contraception was banned in that state. Thomas argued that even if a law is “stupid,” that does not mean that it is necessarily unconstitutional, and it is not within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to strike down a law simply because the justices believe it is stupid.

It is unlikely that Connecticut or any other state would ban contraception today, and the Left knows that, or should know that. They are simply using that “fear” as another way to undermine our federal and republican form of government.

The United States would be better off if all nine justices had the same respect for the Constitution as Clarence Thomas. One valid criticism of Thomas’ judicial philosophy, however, is his apparent acceptance of the Incorporation Doctrine — the view that the 14th Amendment “incorporated” the federal Bill of Rights, applied it to the states, and left it in the hands of federal judges to adjudicate a state’s obedience to the Bill of Rights.

If that doctrine were repudiated, as Thomas rightly repudiates substantive due process, there would be far fewer cases landing in federal courts.

But it is clear that Thomas is fighting the good fight, that he has clearly emerged as the justice on the bench most dedicated to following the Constitution of the United States, and that he is determined to convert his fellow justices to that view.