Deep State-Nazi Hidden Axis

Witness Osh, Kyrgyzstan, a modest outpost in Central Asia. Boiling clouds enliven the sky as a breeze lazily strums the tall grass. Meanwhile a farmer tends his yaks, as clouds of gnats move across a meadow in a body like a mournful specter.

Life here has gone on in a relatively unbroken pattern for thousands of years.

But peasants have noticed something unusual appearing in the soil of late: train tracks. The construction is new — hence half-finished — giving the scene something of the quality of an old Persian carpet that is fraying, its bare threads exposed. Except instead of white threads that made a net upon which the tapestry was to be woven, the modern traveler can see steel rails making a very similar pattern upon which the scene is stitched, rails that seemingly aren’t supposed to be seen at all; the landscape, as it were, a frayed image with the warp and weft of its matting exposed. And, indeed, Osh is frayed at the edges. Threadbare.

In a way, this image of the landscape of the city being like a Persian rug is more appropriate than one would otherwise imagine, since, thousands of years ago, it was a hub used by Iranid nomads who controlled the Silk Road. Spanning from Anatolia to China, it served as the main conduit of international trade for millennia.

While the Silk Road was once presided over by horsemen from the steppes, the Chinese are looking to establish themselves as the new masters of a resurrected trade route, linking East and West. They call their enterprise variously the New Silk Road or the Belt and Road Initiative. And if this grand infrastructure project comes to fruition, towns such as Osh, Kyrgyzstan, and hundreds of others like it strung along the route, will flourish with new economic activity.

In the world of geopolitics, however, such a land-based route for commerce stands as a looming threat to American naval power. The United States derives trillions of dollars from controlling the trade lanes. If China bypasses that, it represents an existential threat to U.S. wealth, power, and imperial significance.

Of course, Russia (a critical beneficiary of the proposed project, for obvious geographical reasons) is aligned with China in this endeavor to create a new Eurasian economic zone.

From the viewpoint of Washington, this is, needless to say, problematic.

As Brazilian journalist Pepe Escobar wrote in a March 2022 article,

Cue to the Russophobic hysteria in Anglo-American media about the Russia-China strategic partnership. The mortal Anglo-American fear is Mackinder/Mahan/Spykman/Kissinger/Brzezinski all rolled into one: Russia-China as peer competitor twins take over the Eurasian land mass — the Belt and Road Initiative meets the Greater Eurasia Partnership — and thus rule the planet, with the U.S. relegated to inconsequential island status, as much as the previous “Rule Britannia.”

England, France and later the Americans had prevented it when Germany aspired to do the same, controlling Eurasia side by side with Japan, from the English Channel to the Pacific. Now it’s a completely different ball game.

So Ukraine, with its pathetic neo-Nazi gangs, is just an — expendable — pawn in the desperate drive to stop something that is beyond anathema, from Washington’s perspective: a totally peaceful German-Russian-Chinese New Silk Road.

If Escobar’s analysis is correct, then it might explain Washington’s recent interest in instigating turbulence in Ukraine (hence creating tensions between Russia and Germany, as Russian oil pipelines threaded through Ukraine to Central Europe are cut off).

In 2014, the United States helped engineer the removal of democratically elected leader Viktor Yanukovych from power in what many in the press framed at the time as a “right-wing coup.” This characterization was due to shock troops being drawn from the neo-Nazi Svoboda Party. None other than Joe Biden was dispatched by the Obama administration to help set up the new regime. As Ukraine was turned into a money-laundering hub and beachhead for NATO, neo-Nazi brigades, with financial support from the West, shelled culturally Russian neighborhoods in eastern Ukraine as a form of ethnic cleansing.

According to a January 27, 2022 report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, approximately 14,200 people have died since 2014. Most of the casualties occurred in the predominantly ethnically Russian Donetsk and Luhansk regions, also known as Donbas.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded eastern Ukraine in what it claimed was a bid to stabilize the region and fend off NATO expansion. Washington, needless to say, placed a different characterization on the situation. From Pentagon press releases, the public was told that Putin violated international law by aggressing against a sovereign nation.

As competing public relations salvos crisscrossed the airwaves, spectators uttered worries about a resumption of the Cold War. And, in many ways, the scenes were more reminiscent of the 1940s than the 21st century, with Ukraine covered in pennants decked with the wolfsangel symbol, swastikas, and media images of Russian tanks lumbering through the streets.

It all seemed like a flashback from an earlier time. But to understand that flashback, it might be useful to trace the echo to its source in history.

Cold War Taken Out of Cold Storage

As WWII was winding down, the United States and its allies wanted to consolidate their power and protect their gains by formalizing them with new institutions. Two men were set up as the chief architects of the new global financial system, British economist John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White of the U.S. Treasury. Both men were avowedly socialist and globalist in their sympathies, with White eventually being implicated in passing on secrets to the Soviets.

Both delegates from their respective countries wanted to create a global system that would supersede the sovereignty of nation-states and forge a “New World Order.”

As Sky News economics editor Ed Conway notes in his book The Summit, “It is occasionally forgotten that the first nation to put forward a formal plan to remould the international monetary system after the Second World War was not America or Britain, but Germany. In July 1940, Hitler’s economics minister, Walther Funk, stood up in front of an audience of journalists and unveiled the German plan for a financial ‘New Order’ across a putative Nazi world.”

Conway adds,

[Harold] Nicolson, a politician ... realised that unless Britain was able to respond, Germany, already looking invincible in mainland Europe, could also lay claim to possessing the most-comprehensive post-war economic plan. So in November he sent Keynes an account of Funk’s plan and asked him to discredit it. Rather predictably, the attempt to force Keynes to sing from a pre-agreed song sheet backfired.

“In my opinion about three quarters of the passages quoted from the German broadcasts would be quite excellent if the name of Great Britain were substituted for Germany or the Axis as the case may be,” he wrote back. “If Funk’s plan is taken at face value, it is excellent and just what we ourselves should be thinking of doing.”

Funk’s plan consisted of a global financial system run using fiat currency, and the formation of a “European Union” with Germany as its head.

But these ideas go back further than Funk.

In point of fact, Funk was the successor to a German banker named Hjalmar Schacht, who was the guiding force behind the creation of the Bank for International Settlements in Switzerland in 1930.

British journalist, author, and foreign correspondent Adam Lebor, in his book The Tower of Basel, writes about the shadowy organization. Despite the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) being the central bank to all the other world’s central banks, it has evaded publicity and remained solidly outside the public’s consciousness.

Lebor writes,

The Swiss authorities have no jurisdiction over the BIS premises. Founded by an international treaty, and further protected by the 1987 Headquarters Agreement with the Swiss government, the BIS enjoys similar protections to those granted to the headquarters of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and diplomatic embassies. The Swiss authorities need the permission of the BIS management to enter the bank’s buildings, which are described as “inviolable.” The BIS has the right to communicate in code and to send and receive correspondence in bags covered by the same protection as embassies, meaning they cannot be opened. The BIS is exempt from Swiss taxes. Its employees do not have to pay income tax on their salaries.

The bank’s first president Gates McGarrah commented in 1931, “The bank is completely removed from any governmental or political control.”

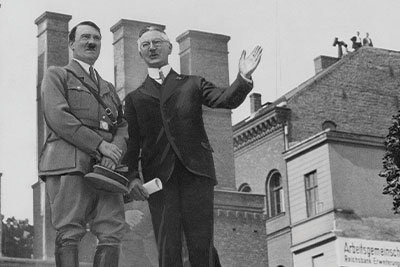

When the bank was founded, it was ostensibly organized to administer German war reparation payments for the First World War. The bank’s principal architect was the aforementioned Hjalmar Schacht, the president of the Reichsbank, who described the Bank for International Settlements as “my” bank.

Lebor adds:

The New York Times described Schacht, widely acknowledged as the genius behind the resurgent German economy, as “The Iron-Willed Pilot of Nazi Finance.” During the war, the BIS became a de-facto arm of the Reichsbank, accepting looted Nazi gold and carrying out foreign exchange deals for Nazi Germany.... After 1945, five BIS directors, including Hjalmar Schacht, were charged with war crimes. Germany lost the war but won the economic peace, in large part thanks to the BIS. The international stage, contacts, banking networks, and legitimacy the BIS provided, first to the Reichsbank and then to its successor banks, has helped ensure the continuity of immensely powerful financial and economic interests from the Nazi era to the present day.

But the bank was a source of growing concern even before WWII.

Back in the wake of WWI, feeling the pinch of the crushing terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Schacht bristled at the punitive reparations payments demanded by the victors. While the United States counseled moderation, and while England was willing to negotiate, France was belligerent, demanding ever more money — impossible sums, given Germany’s economic position in the rubble after the war.

“Germany was paying its reparations by borrowing from other countries,” writes Lebor, and

Such a system was no longer feasible. If the Allies really wanted Germany to be able to pay its obligations, the country needed to become productive again. Instead of lending to Germany, the Allies should lend to underdeveloped countries so they could buy their industrial equipment from Germany. [Some] asked how such a plan could be put into practice. Schacht had a ready answer: by setting up a bank. “A bank of this kind,” argued Schacht, “will demand financial cooperation between vanquished and victors that will lead to community of interests, which in turn will give rise to mutual confidence and understanding and thus promote and ensure peace.”

Hitler’s banker: Hjalmar Schacht (right) and Adolf Hitler in Berlin, May 5, 1934. Schacht was the architect of the Bank for International Settlements and the designer of the modern global economic system. (AP Images)

Conquest by Debt

Thus what are now called “developing countries” were targeted by the bankrupt economic system after WWI. The plan was to place central banks in each country, and, by extending them credit, have them purchase industrial goods from Germany — after which Germany would remit payment for its reparations obligations.

Since all parties concerned among the advanced economies seemed to benefit, the Schacht plan was put into action and the era of the “economic hitman” commenced.

This is, of course, a reference to John Perkins’ book Confessions of an Economic Hitman. In the 2004 exposé, he confided about how he, in his capacity as an economic development expert, was dispatched to Third World countries by the international banking system in order to get struggling nations into debt.

Comments Perkins, “I’m haunted by the payoffs to the leaders of poor countries, the blackmail, and the threats that if they resisted, if they refused to accept loans that would enslave their countries in debt, the CIA’s jackals would overthrow or assassinate them.”

As President John Adams said in 1826, “There are two ways to conquer and enslave a nation. One is by the sword. The other is by debt.” Perkins describes this alternate method of war, as alluded to by Adams. In traditional war, armies invade rival countries to steal their resources. In the new paradigm, “war” would be waged by banks. Credit would be the main weapon. Poor countries were offered loans upon the pretext of helping them with costly new infrastructure projects. To receive the loans, the leader of a nation would be asked to put up as collateral his country’s natural resources. If the leader protested that they’d just built a new airport and didn’t need another one, he would be offered two choices: Take the loan package, build the unnecessary infrastructure, and ensure that his own family and friends were rich for life; or try and keep his citizens from being tax-slaves to foreign banks — whereupon “jackals” would be dispatched to assassinate him and replace him with someone willing to plunge his country into debt. Most leaders, after weighing the options, capitulated. When the respective countries inevitably went into default, the Western banking system would seize their natural resources.

The underpinnings for this system were, needless to say, pioneered by Schacht three-quarters of a century earlier when he founded the Bank for International Settlements. He envisioned the Allies using their considerable influence to spread central banks into all the countries of the world. These new banks in developing nations would be “induced” to buy German goods.

After WWII, new institutions were added to help the Bank for International Settlements achieve these goals. The aforementioned John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White drafted the blueprints for sister organizations: the World Bank (to provide infrastructure loans for war-torn nations after hostilities ended in 1945, as well as for emerging nations going forward) and the International Monetary Fund (set up with the ostensible goal of stabilizing currencies and promoting economic reform in Third World countries, but in reality to create the institutions in their nations to tax the population to pay for crippling World Bank loans).

Needless to say, even after Germany’s postwar obligations were paid off, the system that was initially created upon the pretext of defraying war reparations continued to spread its tentacles around the world.

In the end, its mandate shifted to creating a new sort of “global federalism,” where the sovereignty of individual nation-states was eroded, and a new extra-legal framework was put in place over and above particular countries (analogous to how the federal layer of government was installed over the 50 states in America). Except, the new guiding authority would not be a constitutional branch of government, but a banking system exempt from any law.

Wall Street and Hitler’s Germany

One early apostle for the “New World Order” was none other than Allen Dulles.

Like the Bank for International Settlements itself, Dulles found himself in Switzerland in 1917. From a distinguished American family, both his uncle (Robert Lansing) and his grandfather (John W. Foster) served as secretary of state. Young Allen, after graduating from Princeton and obtaining a law degree, entered the Foreign Service. Stationed in Bern, Switzerland, he worked as a junior intelligence officer at the U.S. legation.

Dulles would later write about how Bern was a hotbed of spies, radicals, and financiers.

At any rate, Dulles soon joined the prestigious law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell and found himself running their Paris office in 1919, just as the Treaty of Versailles was signed. There, he met Hjalmar Schacht.

According to Antony Sutton, “The point to be made is that the Schacht family had its origins in New York, worked for the prominent Wall Street financial house of Equitable Trust (which was controlled by the Morgan firm), and throughout his life Hjalmar retained these Wall Street connections. Newspapers and contemporary sources record [his] repeated visits with Owen Young of General Electric; [W.S.] Farish, chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey; and their banking counterparts. In brief, Schacht was a member of the international financial elite.... He is a key link between the Wall Street elite and Hitler’s inner circle.”

Schacht socialized in the same elite quarters as Dulles, due to the deals the latter brokered for Wall Street firms investing in Germany.

As historian Joseph Farrell writes in Nazi International:

In order to appreciate the German cartel system and its unique power in world finance capitalism at the time, however, it is necessary to go back to the end of World War One, the Versailles Treaty, and the enormous war reparations it imposed on Germany. Since World War One had left the world’s gold standard all but shattered in a tapestry of loans and credits, the outcome was predictable, particularly in Germany’s case: the German government simply could not pay the reparations in any timely and meaningful fashion, and began deliberately to inflate its currency, paying the Allies back with increasingly worthless Reichsmarks, and ruining its own economy in the process as factories shut down and unemployment soared.

It was clear that something had to be done, and the only country at that time that could do it was the only creditor nation in the world with enough liquid capital worth anything to loan: the United States. It is in this context that the 1924 Dawes Plan and the 1928 Young Plan emerged as the latest scheme of international capitalists to milk Germany for all she was worth, for the ruin of the Reichsmark provided them with a golden opportunity “to float profitable loans” with valuable American dollars to the “German cartels in the United States.” Both of these plans “were engineered by these central bankers, who manned the committees for their own pecuniary advantages, and although technically the committees were not appointed by the U.S. Government, the plans were in fact approved and sponsored by the Government.”

The essence of both plans was that the large U.S. central banks floated German bond issues which were paid for by American dollars. In turn, part of these funds were then used by Germany to repay the war reparations imposed by the Versailles Treaty.

But, as Sutton notes in Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, under these two plans “Germany paid out to the Allies about 86 billion marks in reparations. At the same time Germany borrowed abroad, mainly in the U.S., about 138 billion marks — thus making a net German payment of only three billion marks for reparations. Consequently, the burden of German monetary reparations to the Allies was actually carried by foreign subscribers to German bonds issued by Wall Street financial houses — at significant profits for themselves, of course.”

And many of those profitable deals were brokered and overseen by Allen Dulles. One firm he was particularly close to was an outfit called Schrobanco, founded by J. Henry Schröder.

True internationalist: Allen Dulles was an American envoy for the emerging world system, whose embassy he carried out through his tenure as director of the Council on Foreign Relations and his work as head of the CIA. (AP Images)

Working out of London, Schröder set up a trust to invest in numerous German firms, including IG Farben, Siemens, and Deutsche Bank. According to Lebor:

Frank Tiarks, who was a partner in the London branch of Schröder, set up a subsidiary in New York, called Schrobanco. It opened for business in October 1923 and was an instant success. The president of Schrobanco was an American banker named Prentiss Gray, who was a close friend of John Foster Dulles’s, whom Gray had met at the Paris Peace Conference. Schröder’s historic German connections and contacts made that country a natural focus of Schrobanco’s. The company quickly became one of the leading agents for doing business in Germany and later, for processing loans under the Dawes and Young reparations plans. Among Schrobanco’s shareholders were a number of German, Swiss, and Austrian private banks, which included, naturally, the Hamburg branch of J. Henry Schröder, as well as a bank called J. H. Stein of Cologne. One of J. H. Stein’s partners, who was a scion of the Schröder dynasty, would later join the board of the BIS and use J. H. Stein to funnel money from German industrialists to Heinrich Himmler’s personal slush fund.

As a result of these connections, Dulles was at the center of a web of financial interests. But, more importantly, he was becoming known as a sort of glorified mob consigliere with an extensive network of spies.

His growing expertise in intelligence work extended beyond the Versailles period into the ’20s and ’30s (whereupon he worked as the director of the Council on Foreign Relations), and by the Second World War he was the leading spymaster for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Jason Reza Jorjani notes in his essay Black Sunrise:

Dulles would of course go on to serve the OSS, America’s wartime intelligence agency, which he transformed into the Central Intelligence Agency under authorization granted by the National Security Act of 1947. What few people know is that what essentially transformed the OSS into the CIA was Dulles’ assimilation and incorporation of the Fremde Heere Ost or Foreign Armies East, which was under the command of General Reinhard Gehlen and was consequently also known as the Gehlenorg. This was the rabidly anti-Russian Nazi German espionage network in increasingly Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe, which consisted of Czechs, Lithuanians, Estonians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians.

The Ukrainian Role in the Cold War

Ukrainians?

Yes, Ukrainians. The Gehlenorg syndicate (that Dulles later absorbed into the nascent CIA) became the bedrock for the agency’s network in Eastern Europe.

The inherited Gehlenorg has been used consistently since the end of WWII as a hedge against Russian power. Money from Washington has flooded quite freely into eastern Europe to fund neo-Nazi organizations such as the Ukrainian Azov Battalion today.

Victoria Nuland, U.S. undersecretary of state for Europe, stated that Washington had “invested” around $5 billion in political projects in Ukraine over the past two decades. Prior to that, the Reagan administration had allocated funds to build a propaganda infrastructure in the region to cultivate such “useful groups” in their fight during the Cold War. Financing took place, for instance, of Prolog, a nationalist publishing house in the Ukraine, to which the CIA funneled millions. Even before Reagan, however, when Polish-born Zbigniew Brzezinski was President Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor, he engineered the increase in funding for anti-Soviet Ukrainian propaganda.

This is, of course, the same Brzezinski who is famous for his “grand chessboard” theory of containing Russia and having the United States create a pretext to take over Central Asia to control many of the world’s resources, such as rare earth minerals.

But more important than the mineral wealth of the region is its geopolitical significance. Brzezinski’s “Eurasian strategy” is predicated on a much older observation made by Sir Halford MacKinder in a 1904 paper entitled The Geographical Pivot of History.

MacKinder pointed out that civilization, from its earliest stirrings, was based on waterways. All great cities were constructed on the banks of rivers: Sumer on the Tigris-Euphrates, Egypt on the Nile, India on the Indus, China on the Yellow River, and so forth. These hydraulic societies held sway for thousands of years, their commerce helped by these naturally occurring aquatic highway systems. Large empires were constrained by this geographical factor — that is, until the domestication of the horse in 4,000 B.C.

Indo-European-speaking nomads from the Iranian plain were the first to exploit this new mode of transportation. As a result, they could travel thousands of miles where no riverways existed. Eventually, they founded the Silk Road and established the largest land empire the world had ever seen: that of the Golden Horde.

Promoting “international order”: During his tenure as national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter, Zbigniew Brzezinski promoted the idea of America as a “thalassocracy,” i.e., a maritime power. (AP Images)

MacKinder notes that the hinge upon which history pivoted was the shift from naval power to land-based power when this happened.

Eventually, the Silk Road went into decline with the rise of Islam in the early Middle Ages, when Muslims forbade Christian merchants from using the Central Asian trade routes. The European solution was to develop deep-sea naval capacity and try to find a new route to China (accidentally discovering America in the process).

With the Age of Exploration, power shifted away from land-based power to naval power again.

MacKinder warned that, if Russia were ever allowed to industrialize, that balance of power could shift back. Empires such as France, Britain, and America could see their fortunes fall as naval power became obsolete as train tracks stitched the Eurasian landmass together and commerce flowed over land once more.

The Revenge of Geography

Fast forward 70 years, and Zbigniew Brzezinski was an articulate exponent of MacKinder’s trepidations. Russia, he said, must be neutralized by the West — and much less due to America’s dislike of communism than for wider geopolitical and historical reasons. And the concerns extended beyond the loss of revenue due to uncollected tariffs from bypassed naval trade lanes. If Eurasia were permitted to harness its own natural resources and take advantage of a consumer market that represented three-quarters of the global population, these currently challenged countries could use their new economic power to dislodge themselves from the Western banking grid.

Foreseeing the emergence of a troubling paradigm shift caused by the rise of countries calling themselves collectively “The Global South,” Brzezinski lobbied for the creation of the Mujahideen in Afghanistan (which morphed into the Taliban) in the 1980s. Its purpose was to destabilize Central Asia and attack the Soviets from their southern flank. It was, moreover, Brzezinski who used the same template to radicalize young men in the Ukraine (on Russia’s western flank) — a radicalization that, in both cases, took on a perverted form of traditionalism. Traditionalism in Muslim countries manifests in radical Islam. In European countries, it tends to take the shape of Nazism.

Such young men, whose frustrations were unwittingly cultivated by the CIA, were seen as useful tools in the larger struggle over control of the Eurasian landmass.

War by Other Means

As British philosopher Herbert Spencer noted in 1873, war tends to change a nation’s institutions. This was no truer than when the United States, under the influence of men such as Dulles, began remaking itself from a republic into an empire on a permanent war footing. To do so, many of the new institutions embedded in the governance framework were patterned on preexisting Nazi institutions. After the conclusion of the war, Henry Kissinger oversaw Operation Paperclip, where top Nazi scientists, spymasters, and administrators were brought over to America as allies in the Cold War. The German V-2 rocket program was turned into NASA under Werner von Braun. The OSS morphed into the CIA, which Harry S. Truman would later describe in 1964 as “an American Gestapo.”And even the new postwar economic system was patterned off of the “New World Order” promoted by Nazi finance minister Walther Funk.

In this new system, nation-states wouldn’t be independent. The Bank for International Settlements would make the ultimate decisions, controlling countries economically through embedded central banks and intelligence agencies that carried out the will of the BIS. And any leader who expressed the retrograde notion of asserting his country’s sovereignty would meet the fate that Kennedy did when he fired Allen Dulles after the Bay of Pigs fiasco (subsequent to discovering that Dulles was interfering in U.S. foreign policy). After Kennedy’s untimely demise, it was Dulles who was called back to run the Warren Commission.

As the BIS openly says, it is not subject to any law from any country, nor are those who carry out its embassy.

In the New World Order, as embodied by the Bank for International Settlements, the power of nation-states would be supplanted. Banks and corporations would take their place. (Incidentally, in 2001, of the top 100 economies on the planet, 51 were corporations. As of 2022, it’s 69.)

The “senate” at which these financial powers convene is the World Economic Forum, run by Klaus Schwab and headquartered in Switzerland. The “executive branch” of this shadow government is also coincidentally in Switzerland, and its name is the Bank for International Settlements. The European branch of the United Nations is also located in Switzerland (specifically, in Geneva). Though initially Switzerland asserted its neutrality as an excuse to remain independent of the United Nations, it joined in 2022, becoming the UN’s 190th member — a surprising move, given the fact that the UN’s complex web of security treaties would vitiate the landlocked country’s dedication to neutrality. (In reality, however, Switzerland has participated in numerous UN bodies and committees since the organization’s founding in October of 1945.)

It was at the end of World War II that the concept of global governance shifted from speculative to concrete. In a digression, it might be added that Aristotle laid out the three basic functions of all governments in Politics: 1) Creating infrastructure, 2) Establishing a judiciary, and 3) Providing for a military. This was done at the end of World War II by forming a World Bank (to fund infrastructure), a world court at the Hague (to create a global judiciary), and NATO (to act as a de facto world military force).

While opponents of the postwar scheme were shouted down at the time, and their concerns were dismissed as paranoia by factions of the Deep State, the reality was that the three basic pillars of a world government had in fact been quietly put into place, capable of being snapped together at any time.

Just as smaller nations found their monetary systems controlled by central banks, the nascent “world government’s” finances (as above, so below) were largely controlled by the Bank for International Settlements from its perch in Switzerland.