Monopoly: Fears, Fallacies, and Facts

In January 2001, Time Warner merged with America Online (AOL). Valued at $350 billion, it was the largest merger in American history.

Critics, including lawmakers and consumer groups, warned that the deal would stifle competition and perhaps even signal the demise of Internet freedom. Senator Mike DeWine (R-Ohio), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s antitrust subcommittee, said the merger raised “a whole host of competition and public policy issues.”

“Is this merger the effective beginning of the end of the Internet as an effective counterweight to traditional media outlets?” he asked.

These fears turned out to be for naught. The bursting of the dot-com bubble; the rise of broadband, which decimated AOL’s business model; and infighting among the various Time Warner divisions all contributed to a speedy collapse of the merger. In 2010, Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes called the merger “the biggest mistake in corporate history.” Fortune dubbed it “the worst merger of all time.”

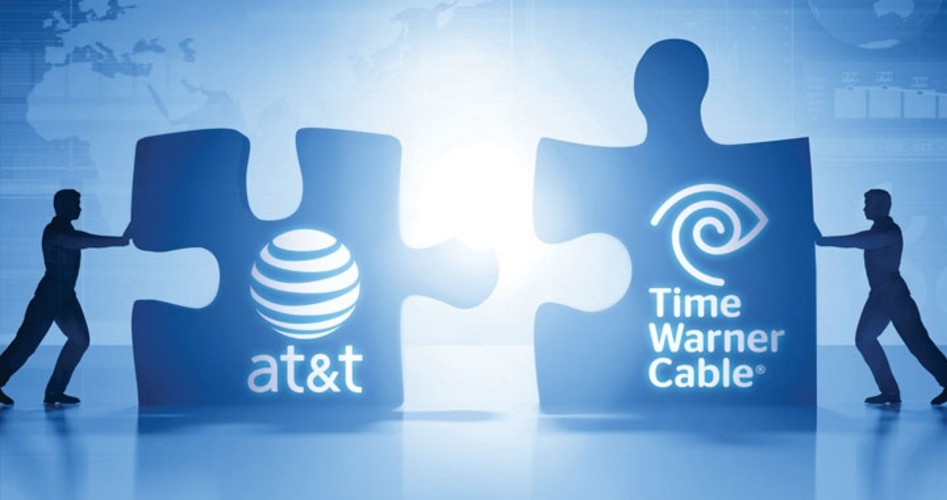

Today, Time Warner is seeking to merge with another large communications company, AT&T, and once again we are being treated to tales of impending doom if the merger is allowed to proceed. This time, the opposition is coming from both a Republican president and an increasingly aggressive antitrust faction within the Democratic Party.

The Justice Department is suing to prevent the merger, arguing that the proposed media conglomerate “would leave millions of television viewers paying more and would slow innovations like video streaming,” reported the New York Times. In a November speech, Makan Delrahim, assistant attorney general for the department’s antitrust division, took a hard line on enforcing antitrust law, a “stance” that “surprised the corporate sector, which had expected easier deal reviews under the Trump administration,” the paper noted.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who is widely expected to seek her party’s presidential nomination in 2020, also spoke out against the merger, saying she supports the lawsuit to block it. Warren went further, however, claiming antitrust enforcement has been far too lax in recent decades, with many agreements between regulators and corporations being “epic failures.”

“We need to demand a new breed of antitrust enforcers,” she declared, “enforcers who will turn down papier-mâché settlement agreements and actually take cases to court.”

“Senator Warren’s theme that antitrust can be used to protect small businesses, entrepreneurs, innovators, workers and just about everyone else from the ‘rich and powerful,’” averred the National Law Review, “shows that increasing antitrust enforcement has become a key party line for the upcoming midterm elections.”

Certainly antitrust sentiment is on the rise among hard-left Democrats, who have formed the Congressional Antitrust Caucus. The caucus is calling for stricter enforcement of antitrust law and, moreover, a refocusing of that enforcement on broader concerns such as mergers’ expected effects on jobs, income inequality, and various other progressive causes — a phenomenon former Federal Trade Commission (FTC) official Joshua Wright has dubbed “hipster antitrust.”

Members of the hipster antitrust movement — they prefer to be known as the New Brandeis school, a reference to former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, a foe of big corporations — believe there was once a golden age of antitrust enforcement in which the U.S. government’s expert regulators had the wisdom to break up corporate conglomerates that were engaging in unfair, anticompetitive practices that harmed not just consumers but society as well. This “golden age,” they claim, ended in the late 1970s when the government, under the influence of the Chicago school of economics, adopted the “consumer welfare” standard for antitrust enforcement, which narrowly focused on whether a proposed merger was expected to result in lower prices or other favorable conditions for consumers. This change, in the hipsters’ opinion, opened up the floodgates for mergers of all types, no matter how harmful.

Trustworthy Antitrust History

In truth, economist Thomas DiLorenzo maintained in a 1991 paper, “There never was a golden era of antitrust.” Antitrust laws were crafted for political reasons, and they have always been enforced selectively — and frequently illogically. They do not exist to protect either consumers or other businesses from genuinely criminal or fraudulent practices but to give politicians and disgruntled competitors a weapon to wield against their opponents.

The first stirrings of antitrust sentiment in the United States occurred in the late 19th century, when small farmers and businesses began clamoring for protection from large corporations, arguing that these businesses were creating a “dangerous concentration of wealth” among entrepreneurs such as John D. Rockefeller and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

“There was no ‘dangerous concentration of wealth,’” DiLorenzo found, noting that the division of national income between labor and capital remained constant between 1840 and 1900, “but many supporters of antitrust legislation found that their own income had fallen (or not increased rapidly enough). The push for antitrust legislation was an attempt to use the powers of the government to improve their economic status.”

In 1890, these interest groups succeeded in getting Congress to pass the Sherman Antitrust Act, a law that was ostensibly aimed at protecting consumers from monopolies but in reality served as a fig leaf for a huge protective-tariff hike.

Ohio Senator John Sherman and his allies claimed that trusts were conspiring to restrict output, thereby increasing prices. According to DiLorenzo, that contention was patently false. In the decade prior to the passage of the Sherman Act, real Gross National Product increased by roughly 24 percent, while output in the allegedly monopolized industries increased by an average of 175 percent. The consumer price index, meanwhile, fell seven percent, with prices in these same “monopolized” industries falling even faster. The Congressional Record shows that lawmakers recognized the trusts’ price-cutting propensities but opposed them nonetheless because they put less-efficient competitors (i.e., those lobbying for antitrust laws) out of business.

Photo: Photo: Maxiphoto/ iStock / Getty Images Plus

This article appears in the March 5, 2018, issue of The New American.