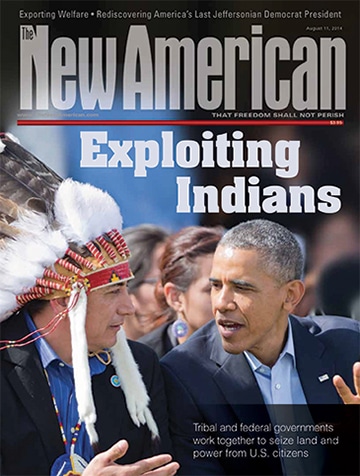

Exploiting Indians

Many of Doug Thompson’s constituents are nervous. Some are angry. More still are confused. The soft-spoken Wyoming cattle rancher has been ranching in vast Fremont County since 1970, and has been on the County Commission for 14 years, serving as the chair for a decade now. Despite the brutal winters, it is a quiet and beautiful area, where hard-working descendants of pioneers, alongside Native Americans, have eked out a meager living from the land for over a century, mostly in agriculture, tourism, and energy. Slightly more than 40,000 people live there, spread out across a county that is about the size of Vermont.

Thompson’s ranch, located some 45 miles from the local Indian reservation, is not in jeopardy right now. But the same cannot be said, at least not with any degree of certainty, for the rights of thousands of other citizens in the area, whose businesses, lands, self-government, access to water, and potentially even livelihoods may be under threat — at least if the Obama administration and its increasingly lawless Environmental Protection Agency get their way.

In December, defying established federal law and multiple U.S. court rulings, unelected bureaucrats at the EPA made Fremont County perhaps the most high-profile battleground in a quiet but disturbing assault taking place across much of the nation. Working with other departments, the EPA unilaterally purported to place the city of Riverton, Wyoming, inside the nearby Indian reservation’s boundaries — and more importantly, under the jurisdiction of tribal authorities for the Wind River Indian tribes. At least two smaller towns, Kinnear and Pavillion, were also decreed by the EPA to be within tribal borders.

Riverton is the largest town in Fremont County, home to more than one-fourth of the population and serving as the economic hub for the region. In 1905, Native Americans were paid and Congress passed a law opening up parts of the area to settlers, decreasing the size of the vast Indian reservation. By most accounts, relations between Native Americans and other county residents had generally been peaceful and friendly. As the federal government and the tribal governments it funds team up against non-tribal members, though, tensions are reportedly rising.

The boundary dispute that recently made headlines across America with the EPA ruling has been simmering quietly under the surface for years. Wyoming officials and experts say Congress settled the question more than a century ago — along with the courts in subsequent rulings. But the Obama administration, apparently not agreeing with the law or the courts, handed over more than a million additional acres and three non-Indian towns to the tribes with a simple decree.

“My contention is that this is a congressional call,” says Thompson, the rancher and County Commission chair. “It seems like under this current administration, they are trying to do all these things administratively, which is totally inappropriate. It’s not up to a political regime to do this. It’s a basic philosophical problem. The EPA should not be re-defining boundaries or subjecting citizens to a government that they have no formal say in — voting, access, and so on.”

In an interview with The New American, Thompson explained that there has been a longtime effort by the tribal governments to reestablish the old boundaries of the reservation. Using litigation, for example, the federally funded tribal authorities — flush with federally granted casino-monopoly cash and U.S. taxpayer funds — have tried to establish jurisdiction over the land and its non-Indian inhabitants, too. Those efforts failed. However, following the lead of other Native American governments across the country, tribal leaders in Fremont County tried a new tactic.

According to an analysis of government documents, the EPA decision stemmed from a 2008 request by the Wind River Indian tribes to obtain “treatment as a state” (TAS) or “treatment similar to a state” (TSTS) under federal environmental regulatory schemes. In this case, it was done via an amendment to the Clean Air Act, which purports to impose EPA mandates on state governments. Once approved, the EPA ruling TAS allows tribal authorities to be “treated as a state” for regulatory purposes. That means tribal authorities can receive even more federal taxpayer dollars under the guise of implementing and enforcing various EPA regulations, which normally would be handled by the state government.

If the federal government and the tribal governments it funds succeed in Fremont County, everything from water rights and air quality to land use — in some cases even 50 miles beyond whatever the reservation boundary is determined to be — could be regulated by tribal authorities, over whom non-tribal members have no vote. For now, state and local officials have been instructed by the governor to continue operating as usual while the state government prepares to battle the Obama administration in court.

Among other major problems, the EPA ruling, made in consultation with the Obama administration’s Department of Interior and the Justice Department, might even make the city of Riverton ineligible for many state and local services, including law enforcement and emergency response. It also raises numerous concerns over taxation, regulation, permitting, and a wide range of other issues involving jurisdiction, officials and experts say. Even tribe members convicted of crimes in state courts may be able to challenge the state’s jurisdiction because they can claim the crimes they committed were perpetrated on the Indian reservation under tribal jurisdiction; in fact, it’s already happening.

Under the arrangement prior to the EPA’s ruling, the Indian reservation was under tribal jurisdiction, along with any lands held in federal trust for the tribes outside the formal reservation boundaries. The federal Bureau of Indian Affairs and other agencies handle much of the governance, despite claims of tribal “sovereignty” parroted by the feds and the tribes. Non-members of the tribes, meanwhile, were subject to state and local authorities such as the sheriff and state regulators.

“What this would do is put Riverton, the irrigation districts, and the main non-tribal areas — those are state, county, and municipal jurisdictions — under the tribes’ governments. They could assert significant jurisdiction, up to and including taxation and regulation,” Thompson said. “That doesn’t mean if the EPA decision stands, that would happen, but in other states that has happened. The tribes say, ‘We’re not gonna do that right now.’ Well, maybe they aren’t going to now, but all they have to do is go to court and say this is their jurisdiction.”

When the EPA decision was first announced, Thompson explained, many county residents were confused and frightened. “The first question that came out was, ‘What is the security of the deeds to our property?’” he said. “The answer is that, if you own the property, you still own it. The difference will be in how you can use your property.” And that difference, of course, is crucial, since property could be useless if it cannot be freely used.

“If you bring another governmental jurisdiction into the mix — say there were permitting regulations exerted — then you’d have to get a tribal permit as well,” the commission chair explained. “Now that hits on the foundational problem in this whole deal: You are subjecting non-tribal members to a governmental entity that they have absolutely no say in, because they are not tribal members. You’re totally subject to a tribal government authority that you have no say in. You can’t vote for the leaders. If they don’t want to meet you, they just shut down the meeting. That’s the crux of this whole thing.”

“The non-tribe members are greatly concerned,” Thompson said of county residents. “Citizens are nervous about what this means — they’re hearing a lot of mixed messages. They hear from tribal members ‘we’re gonna take your land back, we’re gonna regulate you out of business,’ so they’re justifiably concerned.” Even the mayor of Riverton says he has received similar threats.

State-level Resistance

In Wyoming, the deeply controversial executive-branch machinations that purported to place Riverton, Kinnear, and Pavillion inside tribal boundaries have sparked a massive outcry among residents and state officials, with Wyoming Governor Matt Mead and his administration vowing to fight back.

“My deep concern is about an administrative agency of the federal government altering a state’s boundary and going against over 100 years of history and law,” the governor added in a statement. “This should be a concern to all citizens because, if the EPA can unilaterally take land away from a state, where will it stop?” The governor also thanked the Wyoming attorney general and his staff for urgently preparing a thorough review of the historical record on the issue. “This analysis shows how flawed the EPA was in its legal justification for its decision,” Mead said, adding that all avenues would be pursued. “The federal government clearly had a predetermined outcome it sought to uphold.”

In a petition to EPA bosses asking the agency to reconsider and stay its decision, Wyoming Attorney General Peter Michael said the Obama administration’s scheme depends on “a host of faulty factual and legal conclusions.” The document cites a broad range of statutes, treaties, and court decisions, arguing that the EPA essentially cherry-picked arguments in a manner “more akin to advocacy” to reach a determination that is simply “wrong.” The attorney general said that the decision would strip the state of its sovereign right to exercise jurisdiction over lands “rightly within its control” and that it must be overturned — or at least delayed until the courts can review it. “A failure to do so will likely lead to civil and criminal jurisdictional turmoil, irreparably harming the public interest,” he warned, echoing widespread concerns.

Wyoming’s entire delegation to the U.S. Congress has also expressed deep concerns, with Senator John Barrasso blasting the Obama administration for again thinking it “can ignore the law of the land when it suits their agenda.”

EPA and the Tribes

The federal government has been suspiciously quiet since dropping the bombshell on Wyoming in December. The agency did eventually stay its decision as the legal battle in the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals proceeds. Some analysts expect that litigation to eventually end up before the Supreme Court.

Tribal leaders, on the other hand, have responded to the growing uproar across the state — and even the nation — in a variety of ways, particularly by trying to downplay fears and attack critics. As has become typical, tribal officials were quick to suggest that opposition to the EPA decision and the tribal governments’ actions may be based on “racism.” Ironically, even the mere suggestion that everyone should be treated equally under the law regardless of race is often met with howls of “racism” from powerful tribal leaders rolling in federal taxpayer dollars and revenue generated from casino monopolies (granted to tribal governments by the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act).

In Fremont County, tribal leaders have also claimed that they mostly just want “clean air,” though they have also become increasingly bold in discussing the “potential” for further jurisdictional issues that should be “negotiated” rather than litigated. Tribal government leaders at the reservation were not available for comment and did not return phone calls to The New American by press time.

When the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance (CERA), which supports constitutional government, held a convention in Riverton about the ongoing issues, tribal leaders furiously lashed out, even comparing the non-profit group to the Ku Klux Klan. The establishment media in Wyoming disgracefully allowed its pages to promote the smear. However, group leaders and local citizens told The New American that the attacks were so far detached from reality that it was hard to believe the claims were even made — much less printed. CERA’s previous chair, for example, was a Cherokee Indian, and the group has represented Native American tribes whose water rights or other protections were under government assault. More than 50 elected officials attended CERA’s gathering despite the libelous accusations.

The Tip of a Dangerous Iceberg

The Riverton case blew the lid off a phenomenon that has been proceeding quietly across the United States for decades. It turns out that, despite the lack of press coverage, the EPA’s efforts to hand jurisdiction over multiple towns to Indian tribes were merely the proverbial tip of a gargantuan iceberg. Indeed, from coast to coast, multiple federal agencies have been working with tribal governments in a concerted attack on the U.S. Constitution, property rights, self-government, water rights, and more. Perhaps the biggest difference in the Wyoming case is that state officials — who across America are having their campaign coffers stuffed with Indian casino cash — actually spoke out, and the press reported on it.

However, it is not the first time that the phenomenon attracted at least some degree of public scrutiny. In fact, the scandalous federal exploitation of supposed Native American “interests” to justify power grabs surfaced very briefly over a decade ago, when EPA bureaucrats were convicted of fraud in mid-2000 in a case purporting to grant “Treatment as a State” status to three tribal governments in Wisconsin. In that instance, two EPA officials were busted for falsifying documents in a bizarre attempt to justify allowing the tribes to regulate water in and around their reservations, which would have had nightmarish implications for the overwhelming non-Indian majority in the area.

“Aside from the poor judgment displayed by some of the key participants in this case, another factor influencing developments in Region V is EPA’s relationship with the tribes,” explained Dr. Bonner Cohen, now a senior fellow with the National Center for Public Policy Research, after the EPA fraud and power grabs were exposed and prosecuted. “That relationship is characterized by an odd mixture of intimacy and mutual exploitation that has come back to haunt both parties.”

That case, though, was hardly unique. Elaine Willman, who is of Cherokee Indian ancestry, is among a handful of respected experts who can speak credibly on a subject that is deliberately shrouded in obscurity and deception — federal Indian policy. Her husband is also of Native American ancestry and is even related to Sacajawea, the celebrated Indian who served on the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Willman served as the chair of the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance from 2001 to 2007 until accepting the position of director of community development and tribal affairs with the small Village of Hobart in Wisconsin. She still serves on CERA’s board and is working on a doctoral degree in federal Indian policy, one of her passions and an issue she says requires much more attention and some major reforms.

After traveling across the country to visit Indian reservations and conduct interviews, Willman’s worst suspicions were confirmed. The proliferation and empowerment of federally funded tribal governments, working with the federal government itself, threatens the constitutionally protected rights of all Americans, including, ironically, the descendants of the original Native Americans. It threatens self-government, too, she says.

In 2005, Willman published a book on the subject entitled Going to Pieces: The Dismantling of the United States of America. It is packed with examples of abuses stemming from tribal governments in cahoots with state and federal policymakers. America is increasingly being governed by tribalism, she says, a system whereby federally funded tribal governments work with their federal paymasters to attack state sovereignty, private property, the unalienable rights of non-tribe members and Indians, and much more.

Early on in the book, which recounts her 6,000-mile voyage from her native Washington State to New York, she describes massive land grabs in rural Northern Idaho being facilitated by the EPA, the Department of the Interior, and other state and federal agencies. Among other concerns, she explains that tribal governments, with the connivance of state and federal officials getting big campaign contributions from tribal governments, are unilaterally expanding the borders of Indian reservations far beyond what U.S. law permitted. Tribal governments are working to exercise jurisdiction over property owners whose families have owned the land for a century, sometimes even longer. The Coeur d’Alene tribe, for example, with help from federal officials, is among the tribal governments trying to push out the boundaries of the areas they control, with everyday citizens and their lawfully owned properties in the crosshairs.

Among those who have been forced to deal with the problems are Roger Hardy and his wife, Toni, whose grandparents lawfully homesteaded their more than 500 acres of lakeshore land more than a century ago. With help from the EPA, and despite huge legal costs for the Hardys trying to fight it, the Coeur d’Alene tribal government was able to acquire control over a public “walking trail” through the property after a contaminated railroad track fell out of use. Tribe members reportedly regularly enter their private property, sometimes damaging it, sometimes shooting guns at anything that moves under the guise of “ancient hunting rights,” and more. The tribe’s actual reservation has been about 70,000 acres since the late 1800s. Tribal authorities, though, with connivance of federal and state officials, have been working hard to expand its boundaries to the former 350,000 acres. That puts Roger and Toni’s property — along with many others’ — at serious risk.

Aggressive actions by another tribal government in Idaho, the Nez Perce tribe, with several thousand enrolled members, prompted local authorities from across the region to band together in an effort to contain the tribal government’s claims of purported jurisdiction. There, tribal officials were trying to extort gargantuan amounts of money for “permits” from non-Native residents for simple actions such as building a school — on non-reservation land — all while trying to usurp water rights and more.

County and local governments there were providing virtually all taxpayer-funded services to everyone in the central Idaho area, including tribe members. Still, the tribal government was receiving more in federal grants alone than the local and district governments were collecting in total revenues, combined. The tribal government was also bringing in big bucks from an Indian casino and tax-exempt businesses, which have a major advantage over non-Indian businesses due to the taxation arrangements. The tribal government, like others across America, was pouring that money into buying up more land, hiring lobbyists, funding politicians, and employing swarms of attorneys to push its goals through litigation in the courts.

Some of the most alarming tales of joint tribal-federal abuse came from Thurston County, Nebraska, home to the Omaha and Winnebago reservations and numerous non-Indian farmers whose ancestors acquired the land lawfully, often by purchasing it from Indians. Over a decade ago, large swaths of the area, part of EPA “Region 7,” were placed under the regulatory jurisdiction of tribal governments on everything from pesticides to environmental regulations. Non-Indian farmers were suddenly faced with a nightmarish situation of being governed by federal and Indian authorities with whom they held no sway.

Incredibly, tribal law enforcement — mostly from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs — even began harassing and brutalizing some local farmers. In her book, Willman tells the story of the Knecht family, which has farmed the land for four generations. In 2004, Kim Knecht, the son, was on a tractor in his family’s fields when he spotted three Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) tribal police cars speeding toward him. Apparently the Omaha tribal government had decided that part of the Knechts’ lawfully owned farm was actually its property. One of the cars rammed Kim’s tractor before a gaggle of tribal cops jumped out and dragged him off his vehicle, scraping his back in the process. The officers maced him, slammed him on the ground, and put him in handcuffs. Kim’s frantic wife called 911 before running toward her husband in a panic. She was arrested, too. Kim’s father, Vernon, also ran out and demanded that the tribal officers get off his private property. After claiming that the land was on the “reservation,” they eventually did leave, taking Kim with them to a tribal jail and charging him with assaulting tribal law enforcement, ramming their vehicles, and “resisting arrest.” Finally, after thousands of dollars squandered on legal fees, Kim was cleared of all the bogus charges, and a federal judge severely reprimanded the tribal cops. However, no charges were ever brought against the tribal officers for trespassing, assault, harassment, destruction of property, or any other crimes.

Incredibly, just weeks passed before Vernon suffered a similarly traumatic incident at the hands of the tribal cops. After reluctantly (considering what happened to his son) helping his Indian friend feed the tribe’s buffalo, Vernon left his tractor on the reservation at the request of his friend, a member of the tribe. Tribal BIA police then went to tow it away. When Vernon found out, the 73-year-old went to investigate, and sure enough, the officers were hauling his machine away. He got out and explained the situation to the officers. They responded by immediately beating him on the head with clubs, throwing him to the ground, rubbing his face in the gravel, and handcuffing him. Pleading with the officers for his heart medication and covered in bruises, Vernon was eventually taken from the scene to the hospital by paramedics. It took months for his face to heal. Kim, who stayed in the truck at his dad’s request, took pictures of the beating, but considering his own legal problems with the tribal government, he could not do much. Vernon was eventually charged with “stealing hay” and “trespassing” on Indian land, though those trumped up charges were eventually dropped as well. “American citizens … don’t have any rights here anymore,” then-County Sheriff Charles Obermeyer is quoted as saying in Willman’s book.

Even more worrying at the time, Willman explains, were plans to cross-deputize tribal enforcers, giving them power to enforce state law in addition to tribal law, even against non-Indians.

In Washington State, meanwhile, Willman also found similarly troubling trends. To illustrate the lunacy of the EPA “Treatment as States” policies for Indian tribes under the Clean Air Act, for example, she used two maps. The first shows the state government’s air-quality regions under EPA mandates. The second features the areas where “Indian air” would be controlled by tribal governments — essentially the entire state, once the “weighted comment” scheme giving them powers over 50 miles outside reservations is taken into account.

“Regulatory control of America’s air and water directly impacts America’s industries, private sector market places, farming, energy and natural resources,” Willman explains. “TSTS [Treatment Similar to a State] is the stealth bomb that has been launched and is heading for the target. Highly urbanized areas such as Portland, Seattle, and the entire West Coast could soon become beholden to multiple approvals required by Indian tribes in order to open a business or conduct any activity within their jurisdictions.” Across America, wherever there are self-styled “sovereign” tribal governments, the threat is there, too.

The Department of Interior has also been plotting to hand over massive swaths of public lands to tribal government managers. Public spaces deemed to have “special geographic, historical, or cultural significance to self-governance tribes,” for example, could eventually be run by tribal authorities. Even “close proximity” could be enough to let tribal governments take over governance of dozens of national parks and “wildlife refuges” across America. Willman suggests access to the areas is being “systematically” restricted — potentially even to the point of denying access — to everyone except the Native American Indian population. In recent years, as just one example, tribal governments in South Dakota, with full federal connivance, have been seeking control over huge swaths of the Badlands National Park. Analysts also said that plot could set a “precedent” for other tribes across America to seize control over national parks. However, at least in this case, tribal and non-Indian residents in the area are resisting the giant land grab being cooked up by the tribal governments and the federal one.

In Montana, among the stops on the journey, Willman and her colleague, Kamie Christensen Biehl, found a wide range of problems brought about by joint federal-Indian government abuses. Since the book was written, the situation has only grown worse. As just one example, as this article is being written, non-tribal members across 11 western Montana counties are being threatened with potential ruin through the loss of water rights to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT). Especially under threat are the more than 20,000 non-Native Americans who lawfully own land and property in the Flathead Indian reservation, home to about 4,000 Indians who are openly seeking to reclaim all of the land that was sold off beginning in the early 1900s.

On July 8, a busload of non-Native locals from the region, along with a caravan of cars full of ranchers, descended on Helena to testify against the plot to hand over control over water to the tribal government and its federal “partners” as part of a new, perpetual “compact.” If approved, the tribal government would be effectively in full control over the property and destinies of tens of thousands of non-Native citizens by controlling their access to water — perhaps the single most essential resource.

Clarice Ryan, an activist with Concerned Citizens of Montana working to fend off the attack on water rights, told The New American that the land grabs are “happening nationwide, with the federal government using the reservations to gain control of land, water, air, and energy. I truly believe that what is happening right here on our Salish Kootenai Reservation could become the pilot program and poster child laying the groundwork for the policies and political strategies nationwide.”

The above examples represent but a tiny fraction of the abuses perpetrated against citizens of all races by the federal government and its dependent so-called sovereign tribal governments. While a few court rulings have sought to rein in some of the wildest abuses — EPA just got unanimously smacked down in the liberal D.C. Court of Appeals for trying to override the government of Oklahoma in Indian country and essentially regulate dust — the lawlessness is still growing.

How Did This Happen?

The hundreds of tribal governments and the federal government have developed a sort of symbiotic relationship benefiting both — at the expense of the rights of Americans and Indians alike. Of course, it is important to draw a distinction between tribal governments and Native Americans. Estimates suggest just one in five Indians is actually registered as part of a tribal government or lives on a reservation. While all Indians are and have been U.S. citizens for generations, only a handful actually willingly subject themselves to the rule of federally funded tribal governments.

There are more than 550 officially recognized tribal “nations” spread across about 30 states. Most of them have a Department of Interior-approved “constitution” under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which establishes the tribe’s governing system. Once recognized and approved, the tribal governments then become quasi-dependent “sovereigns,” with huge amounts of federal tax dollars and supposed “sovereignty” delegated to them by the federal government. “It’s all a horrible hoax,” Willman told The New American in one of a series of extended interviews exploring federal Indian policy.

Of course, the reservation system has, by any objective measure, been a miserable failure. As The New American has documented in the past, statistics for life in Indian country paint a grim tale of alcoholism, violence, drug abuse, broken families, dependence, poverty, abuse, suicide, lack of education, and a general feeling of hopelessness. Many tribal leaders benefit from the system, of course, but for members, generally speaking at least, misery reigns across most of Indian country.

“This establishment thrives because of the perverted interpretation of sovereignty. The Indian establishment — I’m talking about tribal government and the Bureau of Indian Affairs — wield a lot of power in Washington,” Faron Iron, a member of the Crow tribe who has served on the tribe’s executive committee but disagreed with the tribal government’s policies, is quoted as saying in Willman’s book. “They purport to be Indian experts and they speak for the common Indian, but it isn’t so. They protect the system itself, which benefits them. As far as people, they merely serve as statistics to qualify for funds or whatever else they need. The people are basically to be used, is what it is.”

But how did the accelerating joint tribal-federal assaults on liberty, property, and self-government come about? Willman says one of the key tools is the exploitation of guilt. As documented in innumerable history books, the descendants of Europeans who arrived in America over hundreds of years were often brutal toward Native Americans, as was the federal government. While few living Americans today participated in historical atrocities against Indians, a feeling of collective guilt still pervades the culture. This is a crucial weapon in allowing the federal government and its Indian government “partners” to run roughshod over the rights of Americans with little protest or media coverage. “They have abused white guilt,” Willman explains.

Another key tool is the deluge of cash facilitated by the feds. “You can time the explosion and the abuse of Indian policy to the emergence of federal casino monopolies in 1988,” Willman explained. “As soon as that act passed, that money truly did start buying up the political process, and that is when the abuse really blew up, you can trace it. Before that, there had been a live-and-let-live atmosphere between communities. That was the tipping point — these gaming tribes started getting mega-wealthy. The money was intended to improve the lives of people on the reservations, but it has not done so. It’s just money for the tribal leaders and political contributions. That financial leverage really ties in with the expanded symbiotic relationship.”

After visiting nine reservations, Willman summarized the process that occurs: “A tribe gets a casino(s); a tribe buys political and legal power; surrounding counties, towns and citizens are bullied; a tribe buys or economically forces out landowners/businesses; elected officials get quiet, or get purchased; non-tribal lands and economies dwindle quickly; thousands of American citizens lose — sometimes everything; tribalism as a governing system” then eventually replaces self-government.

It is also important to understand how these reservations function economically — much more akin to central planning and socialism than to American notions of free markets. The tribal government largely controls jobs, the economy, the distribution of federal tax dollars, and more. “Centralizing and expanding the power of the federal government in various states over citizens, and spreading socialism — tribal governments — as a governing system is a marvelous way to domestically undermine the principles of our U.S. Constitution,” Willman says.

Of course, much of the trend is fueled, as with most ongoing assaults on freedom, by Americans’ own tax dollars and the shroud of secrecy that surrounds it all. Willman says, for example, the “total power” of federal Indian policy is based “entirely upon the secrecy and intentional absence of studies done, or audits completed.” Consider President Clinton’s “executive order” in 2000 establishing an “Indian Office” in every single federal agency. Each of those agencies then created financial programs, many of which distribute taxpayer funds to tribal governments. Before that, most of the federal funding went through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Now, nobody even seems to know how much federal largess is flowing to tribal governments. When CERA held a conference a few years ago in Washington, D.C., a keynote speaker was George Skibine, a high-ranking BIA official. When asked by a CERA board member whether BIA had ever audited how much annual funding goes to the more than 550 tribal governments, he reportedly responded: “We’ve been unable to do that.” Apparently there was one attempt to calculate how many federal dollars from all agencies are distributed to the tribes, but it turned out to be impossible.

As far as the constitutional authority underpinning the developments, experts say it is shrouded in mystery as well. “For at least 29 states that host Indian tribes, this is death by a thousand slashes over a long period of time, to intentionally erode state jurisdiction, administrative or regulatory authority within its own boundaries. The Congressional environmental acts of the mid ’70s became a marvelous tool,” Willman said.

Obama Steps Up the War

As if the problems were not already dangerous enough, the current administration is stepping up the federal exploitation of Native Americans in its effort to “fundamentally transform” the United States. In June, for example, Obama and his wife visited the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Nation in North Dakota to tout his accomplishments and his administration’s “partnerships” with American Indian tribes. “My administration is determined to partner with tribes,” Obama boasted at the summit. “It takes place every day on just about every issue that touches your lives.”

Before the gathering, Obama published a June 5 op-ed in Indian Country Today boasting of his efforts and promising more to come. “As president, I’ve worked closely with tribal leaders, and I’ve benefited greatly from their knowledge and guidance,” he said. “That’s why I created the White House Council on Native American Affairs — to make sure that kind of partnership is happening across the federal government.”

The powerful council was created by an “executive order” last year. The purpose of the order, according to the document itself, was to “promote and sustain prosperous and resilient Native American tribal governments.” While UN agreements on indigenous populations were not mentioned, the controversial decree incorporated more than a few elements of global schemes currently being used worldwide that will be addressed further down.

Tribal government leaders were happy about Obama and his efforts, too. “The best thing that’s happened to Indian Country has been President Obama being elected,” claimed Dave Archambault II, chairman of Standing Rock. Ironically, though, the reservation Obama visited is itself a testament to the utter devastation wrought by federal Indian policy. Despite a federally granted casino monopoly, almost half of the Indians there live in poverty. About 50 percent drop out of high school. An estimated 86 percent of the tribe’s members are unemployed. Alcoholism, obesity, sexual violence, crime, and suicide rates are off the charts. On other reservations, the numbers are even grimmer.

The Obama administration even hosts annual summits for tribal government leaders in Washington, D.C., to meet with top White House officials. Obama has also taken steps to increase “tribal sovereignty” at the expense of state officials by, for example, allowing tribal governments to bypass governors and apply directly for federal emergency and economic development “grants.”

All across the Obama administration, departments are working with Indian governments on deeply controversial programs that have flown largely under the radar. The Justice Department, for example, recently established a permanent “office of tribal justice.” Under an agreement reached amid a lawsuit, the Department of the Interior is now spending billions of dollars buying up land to put in “trust” for various Indian tribes. Obama is also in the process of relaxing the requirements to become a “tribe” and begin receiving federal handouts and vast new regulatory powers to assault property rights, state sovereignty, and the U.S. Constitution.

In recent years, the trends have accelerated at breathtaking speed. If U.S. policymakers do not take action to rein in the administration's ongoing exploitation of its dependent tribal governments in the war on freedom, many more Americans will soon find themselves in federal-tribal crosshairs — with disastrous consequences.

— Photo at top: AP Images