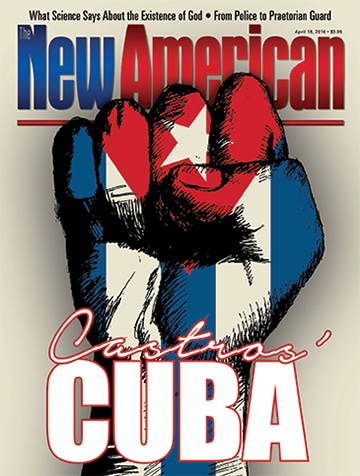

Castros’ Cuba

President Obama traveled last month on an official visit to Communist Cuba, the first such trip by a sitting American president since Calvin Coolidge visited the island in 1928. The trip came less than a year after Obama and Cuban dictator Raúl Castro met in Panama in April 2015 and only six months after their second meeting at the United Nations this past September.

Obama, hopeful for a dramatic improvement in relations between the United States and Cuba, commented that he believes Castro to be a pragmatist and not an ideologue, and that Castro desires change in Cuba, presumably, according to Obama, toward a more open and free society. That expectation of a loosening of the grip of Cuba’s totalitarian system was repeated by Obama during the visit itself, despite the Cuban regime’s rounding up and jailing of dissidents on the weekend prior to the visit.

One dissident, Dr. Guillermo Fariñas Hernández, kept under house arrest during the visit, commented on the recent thaw in United States-Cuban relations: “Yes, things have changed since [diplomatic] relations [between the U.S. and Cuba] were restored. Beatings have increased, threats have increased. Impunity has increased. Aggressiveness has increased.” How, then, is it possible that Cuba is now on the road to greater freedom? Of what benefit to either the American or Cuban people is this softening toward what is still a hardline Communist nation? We will consider these questions momentarily, but first let us examine how Cuba became what it is today.

Before the Castros

The island of Cuba was discovered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage in 1492 and became a Spanish possession. The first Spanish settlements were established in 1511 and soon spread throughout the island. Over time, the island’s significance came especially from its rich soil, abundant rainfall, and subtropical climate, which together are perfect for growing certain crops. Tobacco became the principal crop at first, but in the 19th century it was mostly supplanted by the production of sugarcane. For a while, Cuba became the world’s foremost producer of sugar, both in quantity and in quality.

Throughout the 19th century, attempts were made to achieve independence from Spain. Inspired by various independence movements throughout Latin America, secret revolutionary organizations were formed. In the first half of the 19th century, the Spanish government was successful in suppressing these groups, but in the latter half, three wars were fought by Cubans to achieve independence: the Ten Years’ War of 1868-1878; the Little War of 1879-1880; and the War of Independence, which began in 1895 and ended with American intervention in 1898 (the Spanish-American War) and full independence in 1902. As in other countries in that region of the world, there was a good deal of instability in the governments of Cuba. In 1909 and again in 1912, American troops occupied the country to restore order.

In 1933, a leftist revolutionary uprising overthrew the administration of President Gerardo Machado and put Ramón Grau San Martín in power as the head of what came to be called the “One Hundred Days Government.” Grau himself was a moderate reformer but was surrounded by radicals in his administration. That government was overthrown in January 1934 by Army Chief of Staff Colonel Fulgencio Batista, who installed a series of provisional governments throughout the remainder of the decade.

In the election of 1940, which was reportedly open and fair, Batista won the presidency. He was succeeded in office by Grau, who was elected in 1944, and Carlos Prío Socarrás, elected in 1948. Prío’s period in office was marred by a substantial increase in government corruption and political violence. Consequently, in March 1952, Batista, in concert with leaders of the military and police, seized power to prevent the country from sinking into complete chaos. The outcome of free elections in 1953, which made Batista legally the president, seemed to signal the approval of most Cubans of the coup of the previous year, since the country had grown impatient with the seemingly endless disorder.

About Batista’s administration one can say both bad things and good. On the bad side, corruption was not eliminated and organized crime, which had gained a considerable toehold in Cuba immediately after the Second World War, continued to thrive. On the good side, the nation enjoyed tremendous prosperity in the 1950s. Wages in Cuba were the eighth highest in the world. The country was blessed by a large and growing middle class, which constituted approximately one-third of the population. Social mobility (the ability of members of one class in the social strata to rise to higher levels) became a genuine reality. Of the working class, more than 20 percent were classified as skilled. During the Batista years, Cuba enjoyed the third-highest per-capita income in Latin America and possessed an excellent network of highways and railroads, along with many modern ports. Cubans had the highest per-capita consumption in Latin America of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones, and radios, and was fifth highest in the number of television sets in the world.

Cuba’s healthcare system was outstanding, with one of the highest numbers of medical doctors per capita in the world, the third-lowest adult mortality rate in the world, and the lowest infant mortality rate in Latin America. Cuba during the 1950s spent more on education than any other Latin American country and had the fourth-highest literacy rate in Latin America.

President Batista built part of his following through an alliance with organized labor. As a result, workers by law worked an eight-hour day, 44 hours per week. They received a month’s paid vacation, plus four additional paid holidays per year. They were also entitled to nine days of sick leave with pay per year. In short, while things were not perfect in all of the areas just noted, they were nevertheless remarkably advanced and were gradually improving. Yet, much work remained to be done in rural regions, where poverty and the lack of a complete modern infrastructure remained a problem.

The Revolution

In July 1953, a little-known revolutionary named Fidel Castro, his brother Raúl, and a small group of rebels attacked a military barracks in the southeast of the country hoping to spark a revolution, but were defeated. The Castro brothers were captured and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Unfortunately for Cuba and its people, President Batista declared a general amnesty in 1955, which set the Castros free. The two then traveled to Mexico where they, in conjunction with Argentinian Marxist terrorist Ernesto “Che” Guevara, organized a revolutionary group known as the “26th of July Movement,” the aim of which was to overthrow the Cuban government and seize power. In December 1956, the group of some 82 fighters boarded a yacht and sailed to Cuba, where they were confronted by elements of Batista’s armed forces. In the ensuing clash, most of the insurgents were either killed or captured. However, the Castro brothers, Guevara, and a small group of about 12 others escaped and fled into the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they launched the beginnings of the revolution that would bring Fidel Castro to power.

Castro portrayed himself at that time as a devotee of democratic rule, contrasting that with Batista’s non-democratic authoritarianism, and promised American-style freedoms and an end to dictatorship. Some members of his 26th of July Movement, and even a few members of the leadership corps of that organization, were actually anti-communists, misled by Castro as to the true nature of his ultimate goals. The propaganda about a return to a representative and just government was widely believed, particularly among the poorer classes, students, and some intellectuals. Consequently, Castro’s movement grew as people hoped for an end to corruption, political upheaval, and revolutionary violence. Those people were soon to be sorely disappointed.

During the late 1950s, after Castro had begun his revolutionary activities in the mountains of southeastern Cuba and up until Castro grabbed the reins of power, two men served as U.S. ambassadors to Cuba: Arthur Gardner, who served from 1953 to 1957, and Earl T. Smith, who served from 1957 to 1959. In testimony before the U.S. Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, Ambassador Gardner declared on August 27, 1960 that “U.S. Government agencies and the U.S. press played a major role in bringing Castro to power.” He also testified that Castro was receiving illegal arms shipments from the United States, about which our government was aware, while, at the same time, the U.S. government halted arms sales to Batista, even halting shipments of arms for which the Cuban government had already paid. Senator Thomas J. Dodd asked if Gardner believed that the U.S. State Department “was anxious to replace Batista with Castro,” to which he answered, “I think they were.”

Ambassador Earl T. Smith testified before the same committee on August 30, 1960. He declared in his testimony that, “Without the United States, Castro would not be in power today.” Smith wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times in September 1979 in connection with the communist revolution in Nicaragua that put the Sandinista regime in power. Smith wished to illustrate how forces within the U.S. government brought both ultra-leftist governments to power. He wrote: “After a few months as chief of mission [that is, as Ambassador to Cuba], it became obvious to me that the Castro-led 26th of July movement embraced every element of radical political thought and terrorist inclination in Cuba. The State Department consistently intervened … to bring about the downfall of President Fulgencio Batista, thereby making it possible for Fidel Castro to take over the Government of Cuba. The final coup in favor of Castro came on Dec. 17, 1958. On that date, in accordance with my instructions from the State Department, I personally conveyed to President Batista that the Department of State would view with skepticism any plan on his part, or any intention on his part, to remain in Cuba indefinitely. I had dealt him a mortal blow. He said in substance: ‘You have intervened in behalf of the Castros, but I know it is not your doing and that you are only following out your instructions.’ Fourteen days later, on Jan. 1, 1959, the Government of Cuba fell.”

In Ambassador Smith’s book, The Fourth Floor, he lists the many actions by the United States that led to the fall of the Batista government. Among these were suspending arms sales, halting the sale of replacement parts for military equipment, persuading other governments not to sell arms to Batista, and public statements that assisted Castro and sabotaged Batista. These actions and many others, he wrote, “had a devastating psychological effect upon those supporting the [pro-American, anti-Communist] government of Cuba.”

Left-leaning journalists were as ubiquitous in the 1950s as they are today. One of these, New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews, interviewed Castro in February 1957, reporting that Castro “has strong ideas of liberty, democracy, social justice, the need to restore the Constitution, to hold elections.” Matthews went on to say that Castro was not only not a communist, but was definitely an anti-communist. That story, and other similar stories, created a myth that Fidel Castro was actually a friend of the United States and its way of life, that he was the “George Washington of Cuba” (as television entertainer and columnist Ed Sullivan called him), and that what he fought for was a program of mild agrarian reform, an end to corruption, and constitutional representative government. The myth also claimed that after his victory in January 1959, he was driven into the arms of the USSR by the uncooperative and even hostile attitude of the United States. Curiously, that myth is still repeated to this day. However, the truth about Castro is as far from that myth as possible, as we shall now see.

Communist Connections

Cuba officially established diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union in 1943, during the Second World War. Among the functionaries of the Soviet staff sent to Cuba was one Gumar W. Bashirov, an official of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police (later known as the KGB). Bashirov’s job was to recruit a group of Cuban youths who, over time, could be used to subvert Cuban society and thereby advance the cause of world communism. Among those almost immediately recruited was the young Fidel Castro.

Castro himself admitted in an interview with leftist journalist Saul Landau that he had become a Marxist when, as a student, he first read the Communist Manifesto. For that reason he willingly became a Soviet agent in 1943, when he was only 17 years of age. After the Soviet conquest of Eastern Europe in 1944-45, some of Bashirov’s young recruits were sent to Czechoslovakia for training. But the Soviets forbade Castro himself from joining the Communist Party or any communist front organizations so that he would remain untainted by such associations. Instead, they placed him in reserve, saving him for future eventualities. We see, therefore, that Fidel Castro was a Communist and a Soviet agent long before he took power in 1959.

Fidel Castro’s younger brother, Raúl Castro, also a committed communist since his student days, was (and is), if anything, even more uncompromisingly doctrinaire than Fidel. As a young man he was a member of the Socialist Youth, a part of the Cuban Communist party, then operating under the name Partido Socialista Popular. In February 1953, Raúl flew to Vienna to participate in the Communist World Youth Congress. After the Congress, he was given a grand tour of several Soviet Bloc countries — Romania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia — further cementing in place his devotion to the Communist cause. It was during that trip that he met Soviet KGB agent Nikolai Leonov, who assured him of Soviet cooperation in the upcoming struggle in Cuba. He conferred again with Leonov during his exile in Mexico in 1955.

It is no exaggeration to call Raúl Castro a ruthless, psychopathic killer. During his exile in Mexico and the period in the Sierra Maestra mountains, he was placed in charge of discipline over his fellow guerrilla fighters. That position required the execution of anyone suspected of collaboration with Batista’s security forces, usually by a bullet in the back of the head. Raúl personally did the executing, a job he was quite pleased to perform. Upon the triumph of the revolution in January 1959, Raúl was placed in charge of hunting down all former officials of Batista’s police and military forces. When captured, these men were hauled before a Soviet-style revolutionary tribunal, convicted, and promptly executed by firing squad. Raúl supervised that operation. The killing was soon expanded to include all opposition forces, any individual opponents of the regime, and potential opponents. Tens of thousands, according to some estimates, were executed.

The late Professor R. J. Rummel concluded that up to 33,000 had been executed by 1987. The death toll — impossible to verify — may well be even higher. Some estimates go as high as 200,000! Were it not for the fact that 1.2 million Cubans “voted with their feet” by leaving the island, most of them coming to the United States, the numbers executed would have been vastly greater. So Raúl Castro, now dictator of Cuba since Fidel’s retirement, has never made a secret of his enthusiastic embrace of Marxism and of the systematic butchery that inevitably accompanies that ideology. Moreover, in December 2014, Castro assured his National Assembly that in no circumstances would Cuba renounce its communist system. Yet, despite his murderous reputation and his fanatical devotion to communism, President Obama says, “I don’t think he is an ideologue.” One can only marvel at such naïveté — or whatever it is.

Fast-forward to Today

Besides the mass killings, what has communism brought the Cuban people? Apologists for socialism sing hymns of praise for the Cuban medical system, which they tout as a model for the world. But reality is drastically different from Left-liberal propaganda. What we know about Cuba’s socialist healthcare system we know primarily from the reports of refugees who have fled the island nation and from tourists who have visited Cuba in recent years.

In July 2007, Jay Nordlinger, a journalist with National Review, published an exposé of the Cuban medical system in response to the film Sicko made by leftist activist Michael Moore. In that film, the American medical system is portrayed unfavorably in comparison with the Cuban system, which supposedly is among the best in the world. According to Moore, Cubans receive the finest care possible and it is all completely free. But, as Nordlinger points out, Moore is perpetuating a myth that, though much beloved by the Left, is as fictional as a Jules Verne adventure novel.

So does Cuba actually have a good healthcare system? Sort of. It has an excellent system if one happens to be in the upper echelons of the Communist Party, a high-ranking officer in the military, one of the elite among approved artists and writers, or a tourist with a wallet full of hard cash. That is so because the Cuban healthcare system, like that in the old Soviet Union, is multi-layered.

Nordlinger writes that the very top layer is for medical tourists who are prepared to pay in hard currency for elective surgeries such as facelifts, tummy tucks, or breast implants. These procedures are performed at cut-rate prices to attract customers from the Free World. Here, everything is completely up to modern standards, as good as any healthcare system in the world.

The next level is for the favored classes within Cuba’s supposedly classless society, what the Russians used to call the “nomenklatura,” the bigwigs. Here the standards, the equipment, the supplies, and the medical staff are, like the medical tourist facilities, superlative.

Finally, we have the level for the average Cuban citizen. Here, the hospitals and clinics are a shambles, grossly unsanitary, without modern equipment, and without even the most basic amenities. Patients wait in long lines, and all but the simplest procedures are rationed. Modern equipment is nonexistent. People admitted to a hospital are expected to bring their own bed sheets, pillow, soap, towels, toilet paper, light bulbs, and food. Actual care is minimal, and even the most ordinary medications such as aspirin and antibiotics are extremely scarce. Doctors sometimes must reuse latex gloves and hypodermic needles. One consequence of Cuba’s wretched healthcare system is the reappearance in significant numbers of such diseases as leprosy, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever — diseases long ago eliminated or substantially controlled in all but the most underdeveloped regions of the world.

Cuba prides itself on its very low infant-mortality rate, since that statistic is looked upon throughout the world as a type of benchmark indicative of the overall state of medical care in a country. Prior to Castro, Cuba ranked 13th lowest in the entire world in infant mortality, which was better than in some countries in Western Europe. Healthcare was reasonably modern at that time. Cuba still ranks very low in infant mortality, something that is a bit of a surprise in a country where medical facilities are so primitive compared with the past. How does Cuba do it? Nordlinger writes that pregnancies are very closely monitored and emphasis is placed on prenatal and infant care. However, should there be the slightest sign of difficulty or abnormality, the pregnancy is immediately terminated. Consequently, Cuba has an extraordinarily high rate of abortions, which is how they manage to keep the infant-mortality rate so low. Incidentally, the infant-mortality rate is based on the deaths of children under a year old. Aborting, that is killing, an unborn baby does not count as an infant death.

Cuba has an abundance of medical doctors, yet within its healthcare system there is a shortage. Why? Cuba sends hundreds of doctors abroad to friendly countries and advertises this as a humanitarian gesture. Michael Moore refers to it as an example of Castro’s “generosity.” The truth is, however, that the effort is purely mercenary since Cuba receives payment for this “humanitarianism” to the tune of several billion dollars in hard currency per year.

It has been almost nine years since Nordlinger’s piece was published and it is fair to ask if since that time there has been any improvement in Cuba’s healthcare system. Argentine journalist Belén Marty visited Cuba last year. While there she was able, with the assistance of a Cuban friend, to tour a typical Cuban healthcare facility in Havana, dressed as an ordinary Cuban citizen. She was warned not to speak at all since her Argentine accent would instantly give her away. Her experiences verify all that was published in Nordlinger’s article and show that, far from improving in the last decade, Cuban medicine has continued to deteriorate. Marty noticed at once the shabbiness of the hospital and that the “scarce equipment available gave the building the appearance of a makeshift medical camp, rather than a hospital in the nation’s capital.” Worse still was that “the only working bathroom in the entire hospital had only one toilet. The door didn’t close, so you had to go with people outside watching. Toilet paper was nowhere to be found, and the floor was far from clean.” Most shocking was that “biological waste [was] discarded in a regular trash can.”

Some in Cuba and even some American Left-liberals claim that the U.S. embargo against Cuba is responsible for any deficiencies in Cuba’s healthcare system and living standards. But in answer to this it must be remembered that most of the rest of the world does trade with Cuba.

Dr. Jose Azel, a Cuban exile and senior scholar at the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami, writes in his book Mañana in Cuba: “Currently over 190 nations engage economically and politically with Cuba while the United States remains alone in enforcing its economic sanctions policy. If indeed U.S. policy is deemed as one case of failure to change the nature of the Cuban government, there are 190 cases of failure on the same grounds. By a preponderance of evidence (190 to 1) the case can be made that engagement with that regime has been a dismal failure.”

In other words, the influence of Cuba’s 190 trading partners has done nothing to move the regime in the direction of freedom or seriously to improve living conditions in the country. Consequently, why should we believe that our embargo, if repealed, would accomplish anything substantial insofar as the betterment of the Cuban people is concerned? What we must not do is reward a murderous and criminal regime with the same diplomatic and economic advantages that we allow to friendly governments throughout the world. The embargo, in any case, is not responsible for Cuba’s squalid medical facilities. Cuba lacks the resources to provide modern healthcare because socialism destroys the wealth of a country, just as genuine free enterprise creates wealth in abundance.

How do workers fare in the Cuban “workers’ state”? Unlike the United States, there is, of course, no freedom of speech, no freedom of assembly, no free press, no right to strike to improve one’s working conditions, no free bargaining for workers, and no independent labor unions. The only labor union, the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba, is an appendage of the Communist Party. In theory, workers work a 48-hour week, but are heavily pressured to work additional hours without pay as a contribution to the success of socialism. The average income in Cuba is roughly $20 to $30 per month, the lowest in the Western Hemisphere, but this low pay is partly offset by subsidized rent, food, and utilities. Hence survival is possible, but only barely. Cubans employed by foreign firms are paid many times that received by other Cubans, but are taxed by the government at the rate of 92 percent, retaining only eight percent of what they earn. This is done, the government explains, to assure equality among all Cuban workers.

Rather than the workers’ paradise Castro claimed it would become, Cuba is a country of enforced universal poverty, a place where workers have little or no chance to improve their economic status, a place where the social mobility of the past is but a dream. Therefore, the dismal state in which most of the Cuban people find themselves is fixed, with no possibility for improvement, as long as communism remains in power.

But this stark reality went unacknowledged by President Obama during his trip to Cuba last month. In fact, Obama used the occasion to heap praise upon Cuba under communism.

During a joint press conference with Cuban dictator Raúl Castro on March 21 in Havana, Obama, speaking on behalf of his country, claimed that “the United States recognizes progress that Cuba has made as a nation, its enormous achievements in education and in health care.” He went on to claim: “President Castro I think has pointed out that, in his view, making sure that everybody is getting a decent education or health care, has basic security in old age — that those things are human rights, as well. I personally would not disagree with him.” Of course, he failed to note that this fundamentally flawed view of “rights” entails forcibly taking from some in order to give to others.

Two days later, talking to a group of young people in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Obama observed that “there’s been a sharp division between left and right, between capitalist and communist or socialist,” and that “those are interesting intellectual arguments.” However, he added, “For your generation, you should be practical and just choose from what works. You don’t have to worry about whether it neatly fits into socialist theory or capitalist theory — you should just decide what works.”

And Obama claimed to have found much that works in Cuba. “Every child in Cuba gets a basic education — that’s a huge improvement from where it was. Medical care — the life expectancy of Cubans is equivalent to the United States, despite it being a very poor country, because they have access to health care. That’s a huge achievement. They should be congratulated.”

President Obama does at least acknowledge that the Cuban economy is not working and that there are human rights concerns — to put it mildly. Supposedly, through relaxed relations with the Cuban regime, he and his supporters seek gradually to soften the grim plight of the Cuban people and relax the iron fist of government oppression. But the regime itself insists that communism, and all that goes with that mode of rule, will remain unchanged. Obama’s visit to Cuba has brought prestige and honor to Castro and his totalitarian government and, most probably, will bring an increase in tourism and trade to prop up its dilapidated economy. In short, its aftermath will almost surely be to make the regime’s tight hold on the Cuban people even tighter.

This article is an example of the exclusive content that's available only by subscribing to our print magazine.