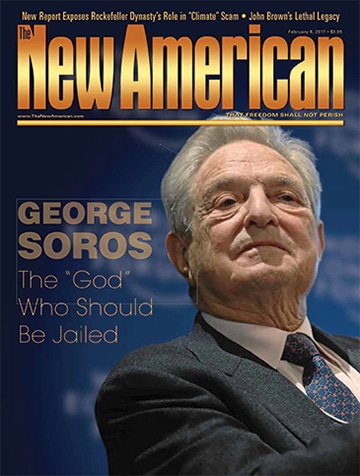

John Brown’s Lethal Legacy

As John Brown’s “Northern Army” approached the Kansas home of the Doyles, poor settlers from Tennessee, two barking bulldogs met them. It was about midnight, and the men did not want the dogs to awaken the Doyle family asleep in their modest cabin — so two of the “soldiers” slashed one of the dogs with their swords. The second dog fled.

The Doyles had moved to Kansas so as not to have to compete with slave labor, and otherwise took little interest in the growing national controversy of slavery. But in the eyes of Brown, they were guilty of being Southerners.

If the loud barking did not awaken the Doyles, the loud pounding on the cabin door did. James Doyle asked, “What is it?”

Lying, one of the men yelled back that they were looking for the Wilkinson place. The ruse worked, and Doyle opened the door, only to be knocked backward as the men rushed into the small dwelling.

“We’re the Northern Army! Surrender!”

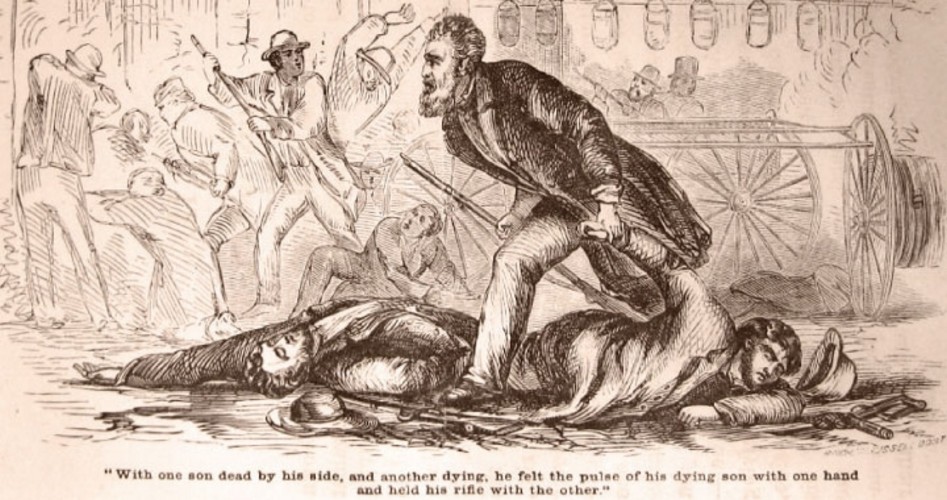

Mahala, Doyle’s wife, tried to speak, but James cautioned her to “hush, mother.” His three sons stood beside him — 22-year-old William, 20-year-old Drury, and 14-year-old John. Doyle and his two older sons were pushed outside, and the intruders then grabbed for the youngest. Mahala begged them to leave the boy alone, and the old man, the apparent leader, roughly pushed the boy back toward her, then slammed the door.

After driving the three men about two hundred yards from the cabin, John Brown took out his revolver, calmly pushed the barrel against Doyle’s forehead and pulled the trigger. One of the other murderers stabbed at the lifeless corpse with his saber.

William was shot in the side, slashed over the head, and stabbed in the face. At that, Drury tried to escape, but was chased down in a ravine. In a vain attempt to ward off their blows, he raised his arms. They cut off his fingers, then his arms. They cut his head open, and finally stabbed him in the chest. Even then, they did not stop, but continued to hack away at the corpse.

But they weren’t through. Wilkinson was next slated for death. Mrs. Wilkinson had heard barking dogs, and woke her husband. The dogs continued barking and finally she saw a man pass by the window, followed by a knock on the door.

They both called out, asking, “Who is that?” To which the man at the door answered that he needed directions to Dutch Henry’s place.

When Allen Wilkinson, a member of the legislature, began to yell out directions, the man yelled back. “Come out and show us.”

Finally, they demanded he come out, or they would break down the door. Despite his wife’s plea not to, Wilkinson opened the door, and the heavily armed men quickly entered the cabin. They took Wilkinson, still in his nightclothes, and pushed him out the door.

They cut his throat and stabbed him in both his side and his head.

Finally, the men killed a man named William Sherman by splitting his head open in two places. When his body was found, one hand was cut off (perhaps in attempting to ward off the fatal blows). Part of his severed brain washed away into the creek.

Not one of the slain owned a single slave.

The man who led the massacre was John Brown, an abolitionist and self-proclaimed captain in the “Northern Army” of Kansas. “Captain” Brown’s unit included four of his sons — Owen, Frederick, Salmon, and Oliver, ranging in ages from 17 to 31 — and a son-in-law. Only two of the murderers were not relatives.

The Pottawatomie Massacre, as it was called, occurred in the darkness of night of May 24-25, 1856, near Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas.

Brown told an associate, James Townsley, the motivation for the murders: “I have no choice. It has been decreed by Almighty God, ordained from Eternity, that I should make an example of these men.” The example was intended to “strike terror into the hearts of the Pro-slavery party.”

Political Murder

These brutal murders took place during the struggle between violent pro- and anti-slavery forces for control of the Kansas territory — known to history as “Bleeding Kansas.” While the body of John Brown, as the song says, is “moldering in the grave,” his example still inspires modern radicals, who justify violence upon the innocent if the cause is “just.”

Following the election of Donald Trump, Brown was specifically cited by some extremists to justify a violent response. As we noted in the December 19, 2016 edition of The New American, Hollywood writer and director Paul Schrader, known for his part in films such as Taxi Driver, The Last Temptation of Christ, and American Gigolo, took to Facebook a few days after the election to call for violent protests. While we have become accustomed to Hollywood leftists threatening to leave the country if their liberal candidate does not win, Shrader took his discontent a step further in his posted response to Trump’s election: “I believe this is a call to violence.” Schrader lamented that President Obama had tried “appeasement” for eight years, and that had now failed. Instead, Schrader argued, “We should finance those who support violen[t] resistance. We should be willing to take arms. Like Old John Brown, I am willing to battle with my children.”

It is interesting to note that Schrader knew enough about Brown to include the historical point that Brown and his sons participated in the Kansas murders. But as we shall see, Schrader also seems to know that behind terrorists such as Brown — and behind similar violent protesters today — are the radical men with the money, when he said, “We should finance those who support violent resistance.” Today, protesters can even be hired through online ads and then directed to illegally block highways, throw Molotov cocktails, set fires, assault people, and damage property.

But how do these financiers of violent protesters, terrorists, and murderous politicians find their revolutionaries? Often, they come to the financiers’ attention through the praise of journalists, as in the case of Herbert Matthews of the New York Times, whose writings are credited with helping to bring communist dictator Fidel Castro to power in Cuba. In 1957, when Castro was just one of many guerrilla-band leaders in Cuba, Matthews wrote, “[Castro] has strong ideas of liberty, democracy, social justice, the need to restore the constitution, to hold elections.” It was all untrue, but after a series of adulatory Times articles, money began flowing to Castro from admirers in the United States.

Such was the case with Brown. The Chicago Tribune and other newspapers lionized the exploits of Brown and brought him to the attention of some prominent Unitarians in New England, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Emerson and Thoreau certainly sympathized with Brown’s militant abolitionism, and there were many others, as well. The most important group of these sympathizers came to be known as “the Secret Six.” They advised Brown, guided his activities, and most importantly, financially supported him. Who were these men? While not all were fabulously wealthy, they did share Brown’s passion against slavery, and they were prepared to support him with dollars as much as they could.

The Secret Six Finance John Brown’s Violence

Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe was one. Howe, a world-renowned medical director who helped educate the blind, was involved in the 1830 revolutions in Paris. Later, when he was chairman of the American Polish Committee in Paris, which assisted the Poles in their revolt against Russia, his actions led to his incarceration in Berlin. Communist Albert Brisbane helped win his release.

Howe’s wife wrote the lyrics for “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” using the music from the song “John Brown’s Body.” The latter was written after Brown was executed in late 1859, following his failed attempt to overthrow the government and launch a slave rebellion with his raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, and it became a favorite of Union soldiers. Doctor Howe helped to popularize “John Brown’s Body,” then Massachusetts Governor John Andrew asked Julia Ward Howe to write a song with “better words.” The new song, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” was published in Atlantic Monthly in February 1862. For abolitionists, the words had a “double meaning,” referring more to Brown and abolitionist activities than to God.

Another of the Secret Six was a Unitarian minister, Theodore Parker. Parker said that the Constitution “was not morally binding.” His concept of morality did not come from biblical Christianity, however, saying that he believed God was going to come up with a “better religion” than Christianity. Although a preacher, he denied practically every important Christian doctrine. He denied the deity of Christ (although he said Jesus was a great man); he also denied the miracles of the Bible, the atonement, the concept of sin, and the divine inspiration of Scripture.

He also referred to the South as “the enemy.”

Gerrit Smith, a congressman from New York, was particularly wealthy — having inherited money from his father, a partner of John Jacob Astor in the fur trade and a dedicated abolitionist. He told former slaves they should “turn their backs” on American Christianity, for it was authored by the Devil.

Franklin Sanborn graduated from Harvard and married into a wealthy family, which allowed him to concentrate on the cause of abolition without worrying about making a living. He inherited his wife’s estate when she died very soon after their marriage.

Another Unitarian minister, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, was strongly opposed to capital punishment, and was a pacifist, yet he supported the murderous activities of John Brown.

Finally, George Luther Stearns was a very wealthy pipe manufacturer. Stearns had met with European revolutionaries such as Giuseppe Mazzini and Louis Blanc, speaking glowingly of them to Charles Sumner (later a U.S. senator) in 1848. Although he proclaimed himself a pacifist, he later urged the complete destruction of the South.

Brown used these men to finance his twisted plan of widespread murder, but they also used him, as we shall see.

Violence to End Slavery Replaces Compromise

These men were all opposed to slavery, which was not an uncommon viewpoint in the North, where the institution had largely disappeared by the 1850s. Many in the North believed, however, that it was an antiquated and dying system, which would eventually cease to exist, violence being unnecessary to end it. After all, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, there were only two states out of 13 in which there no slaves at all. Over the course of the next few decades, slavery had declined and been abolished in all of the North, without bloodshed. The slave trade had been outlawed peacefully throughout the United States by an act of Congress in 1808.

But Brown believed the emancipation of the slaves could wait no longer, and it required not just violence, but genocide. “Better that a whole generation of men, women and children should be swept away than that this crime of slavery should exist one day longer,” he told Emerson. While Emerson later protested that he thought Brown was not speaking literally, he himself said, “If it costs ten years and ten to recover the general prosperity, the destruction of the South is worth so much.”

How had the country moved from ending slavery in a peaceful fashion to the point where the issue had become so divisive? The attitudinal change came gradually, over a generation, as feelings for and against the institution intensified.

It was in 1820 that the issue of slavery first threatened the breakup of the Union. When it was proposed that Missouri enter the Union as a slave state, this caused such opposition in the Northern States that some Southerners expressed the view that perhaps it was time to separate into two countries. But Henry Clay of Kentucky stepped forward with his “Missouri Compromise,” which settled the issue — Maine would enter as a free state to balance it all out, but no more slave states could be formed west of Missouri, if they were north of the latitude line of 36° 30′.

While this compromise averted disunion, aging Thomas Jefferson, from his home at Monticello, expressed concern that, with the slavery issue, “We have the wolf by the ears.”

Then there was the Mexican War. When new lands in the West fell into American hands, another compromise — this time called the Compromise of 1850 — was needed, again coauthored by the aging Henry Clay. One of its provisions, little noticed at the time, was that these western lands be organized into territories with the slavery question settled by the people of the territory.

When Senator Stephen A. Douglas desired the first transcontinental railroad be built west from his home state of Illinois, he knew the territories west of Missouri would have to be organized. His Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 proposed they be organized under the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” — letting the people there decide the issue.

The issue of slavery in Nebraska was not contentious, as it was considered too far north to support cotton plantations, and it did not border a slave state. But Kansas could support cotton plantations and could be another slave state. And thus, fanatics on both sides of the slavery issue flocked to Kansas to “win” the elections for delegates who would decide that issue at a constitutional convention. While most of those who were hardy enough to settle on the Great Plains had little interest in the issue of slavery, many moved into the territory from Missouri, men who were very much interested in the outcome of the slavery issue in Kansas. Missouri slaveholders were concerned — they did not want a “free state” to their west to entice slaves to escape, as they already had that problem in eastern Missouri, with slaves going into the “free state” of Illinois.

In New England and in parts of Ohio, emigration societies sprang up, to encourage migration of antislavery settlers into Kansas, in order to make Kansas a free state. Thus, a bloody clash was almost a certainty.

One of those who went to Kansas, more to fight than to farm, was John Brown. Across from Missouri came those with the opposite goal, called “Border Ruffians.” Then, there were those who just wanted to settle and eke out a living on the rugged Kansas frontier.

Brown’s father, Owen Brown, had been a trustee of the abolitionist Oberlin College. Owen had a low view of Southerners, a feeling he passed on to his son. While John Brown had long been known for a harsh personality, with little regard for those with a contrary opinion, it is not quite clear why he became so agitated about the issue of slavery. Considering the staunch opposition of his father to slavery, it is not surprising that he had always been opposed to it, but he did little about his anti slavery beliefs until he moved to Kansas. In his book Man on Fire, Jules Abels speculated, “The evolution of Brown into the crusader must be viewed in the context of the evolution of the slavery controversy.”

Abolitionism had never been a popular position, even in the North, except with intellectuals such as New England Unitarians Emerson, Thoreau, and the like. Perhaps Brown, who was a reader, became radicalized by their writings. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which personalized the plight of Southern slaves, no doubt heavily influenced him. Again, Stowe was a Unitarian, and the daughter of a minister, Lyman Beecher. Her book was a protest against the tough Fugitive Slave Law found in the Compromise of 1850. Prior to her writing, slavery in the South was more of an abstract institution “down South,” but Stowe’s fictional book created a sympathetic character, Uncle Tom, and touched the emotions of many Northerners, most of whom had previously not had strong feelings about slavery. The book sold in the thousands, and was even made into a popular play — popular in the North, anyway.

Stowe’s brother, Henry Ward Beecher, spoke in Connecticut in the spring of 1855 at a church in New Haven. His message was not about sending missionaries to Kansas to preach the gospel, but rather rifles to aid the abolitionist side. A deacon in the church had told Beecher that 75 pioneers going to Kansas needed the newer breech-loading Sharps rifles, which could fire 10 times a minute, and reputedly hit a target a mile away. When it was stated that the group needed 50 of the newer rifles, Beecher promised that if the group would raise the money for 25 of them, his Plymouth Congregation Church of Brooklyn would furnish the rest. He said that for the slaveholders of Kansas, the Sharps rifle was a greater moral agency than the Bible, so the “Free State” settlers needed them. After this, the rifles were known as “Beecher’s Bibles.”

Whatever motivated Brown, he became a warrior for the cause of abolition in Kansas, and came to believe the murder of innocent civilians was justified in the greater cause.

While Brown was involved in one well-known “battle” in Kansas, known as the Battle of Black Jack, his main contribution to the contest was the Pottawatomie murders. In the so-called Battle of Black Jack, H.C. Pate, a deputy United States marshal and captain of the Missouri militia, was surprised at breakfast by Brown’s forces. After a brief, pitched battle in which many of Pate’s men ran off, Brown took 29 prisoners, making a Brown a “war hero” to the radical abolitionists.

Despite the terror caused by Brown on one side and the Missouri Ruffians on the other side, the side that did not want Kansas to become a slave state began to win out in sheer numbers of settlers. With the pacification of Kansas, Brown needed a new “front” in his war to rid the country of slavery and, in some cases, slave owners.

We will never know the exact role that the “Secret Six” and other New England abolitionists played in Brown’s activities in the late 1850s, because after Brown’s failed raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry many of his financial backers destroyed incriminating letters and papers; however, enough papers survive to paint a fairly clear picture.

The Secret Six Favors Violent Revolution

One of the Secret Six, George Stearns, said, in a discussion about the situation in Kansas, that what the country needed was “a revolution.” Gerrit Smith said the abolitionists were ready to fight the U.S. government. Theodore Parker said bloodshed was necessary to end slavery.

John Brown believed he was God’s “instrument” to cause the revolution favored by the Secret Six. He was certainly the “instrument” of the wealthy and well-placed Secret Six.

For all their later condemnation of the Southern secessionists as disloyal traitors, the conspirators strongly favored the separation of the North and South into two different countries — at least they did before the Civil War. In early January 1857, they convened the Disunion Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. Smith hoped the South would secede, not forcing the North to make the first move. Eighty-nine attended the convention, which was largely mocked by Northern newspapers. While failing to achieve the separation of the North and South, this assembly indicates how serious the attendees took the issue of slavery.

With little support for such separation from most Northerners, it had become apparent to Brown and his backers that direct action of some sort was necessary to provoke the sections into a rupture.

If Brown was going to lead a bloody revolution, he would need a person with more military experience to help train his “army.” The steady contributions of the Secret Six enabled Brown to hire Colonel Hugh Forbes for the job. Forbes had been an officer under Italian radical Giuseppe Garibaldi, a soldier in the Revolution of 1848. Born in England, he was fluent in Italian and French, and worked as a translator for the New York Tribune. Among the European correspondents for the Tribune was Karl Marx, the author of The Communist Manifesto. The newspaper regularly provided space for the opinions of European revolutionaries. Forbes had been introduced to the Secret Six by Senator Sumner — a man who later became an actual communist and who was on a friendly basis with many of the revolutionaries in Europe. It is well established from the history of communist revolutions elsewhere that Marxist revolutionaries seize upon issues such as slavery for their own purposes. If there is a “class struggle,” they exploit it, and if there isn’t such a conflict, they work to create one.

Brown’s Plan for Violent Revolution

Brown’s plan was to lead a slave rebellion in Virginia. He believed that by raiding the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, he could arm the slaves, who were, he contended, ready to rise up against their slave masters. He argued that as many as 500 slaves would “swarm to the standard the first night.” Then, his financial backers could call a convention to overthrow the federal government, which he considered “pro-Slavery.”

It was a fanciful plan, and Forbes offered several objections. He did not believe the slaves would rebel. (Frederick Douglass told Brown much the same thing). Even if he could get a few hundred slaves to actually join him, the military might of the United States was too much, and he would be crushed. Finally, Forbes did not believe the abolitionists in New England would actually support them publicly in armed rebellion.

Other problems that Forbes had with the plan were that Brown was simply not drawing enough recruits for him to train and, perhaps even more important, Brown had ceased to pay him. The disgruntled Forbes threatened the Secret Six with exposure of their role in Brown’s treasonous plans, and this evidently caused a delay of the plan’s execution for several months, from 1858 into 1859.

In preparation for his overthrow of the U.S. government, Brown drafted a “provisional constitution” for a new government. His document provided for a president and a vice president, a congress of only five to 10 members, and a judiciary. The most important position would be commander-in-chief, the position he expected to hold. Although Brown’s constitution proposed to outlaw profane “swearing, indecent behavior, or indecent exposure, or intoxication,” it failed to mention God.

Higginson was supportive of Brown, saying, “I am always willing to invest in treason.” Sanborn’s sentiments were similar: “Treason will not be treason much longer, but patriotism.”

The Attack on Harper’s Ferry and Its Aftermath

When the attack upon Harper’s Ferry finally came, Brown had only 16 white men and five black men under his “command.” It was a cold and rainy day when Brown struck on Sunday, October 16, 1859. The men parked a wagon full of guns and pikes next to a school house — from which Brown expected rebelling slaves could be armed. Upon entering Harper’s Ferry, they quickly took several men hostage who were simply walking the streets. Among the hostages taken was Lewis Washington, a descendant of George Washington.

Around 1 a.m., Brown’s “army” blocked a train entering Harper’s Ferry and shot Hayward Shepherd, a baggage master, who had moved forward to find out what was wrong. The irony of Brown’s “army” murder of Shepherd is that although they were supposedly fighting for the black race, the first man killed at Harper’s Ferry was a free black man.

No slaves joined Brown in his murderous assault upon the federal arsenal. Soon, Marines arrived under the command of Lt. Colonel Robert E. Lee, and after a brief battle, Brown and most of his “army” were either killed or captured. At first, the prevailing Northern reaction to the raid was shock and disapproval. Lee’s comment that Brown was a “mad man” and that the raid was of little importance probably summed up the initial reaction of the country, North and South. Even the ardent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison dismissed it as “misguided, wild and apparently insane.”

Virginia Governor Henry Wise, however, chose to make a huge issue of the raid, and generally excited opinion in the South. He pushed for a quick trial and execution, which swung the sympathy of many in the North to Brown. Meanwhile, northern abolitionists quickly realized the propaganda value of Brown. A November 24, 1859 editorial in the New York Independent well illustrates this change of thought. The Independent’s initial reaction was that Brown was a “lawless brigand,” but their revised opinion, published only a few weeks later, was that he was a heroic personality.

The Independent argued that it was not Brown who was on trial, but slavery itself. “John Brown has already received the verdict of the people as a brave and honest man.” They even contended that Brown was “the noblest man Virginia has seen since its race of Revolutionary heroes passed away.”

Henry David Thoreau said on the day of Brown’s execution, “Some eighteen hundred years ago, Christ was crucified. This morning perchance John Brown was hung [sic].” Not to be outdone by the inflammatory statement of his fellow transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson called Brown a “new saint,” a man who made “the gallows glorious like the cross.” Southerners were shocked at such remarks, which they considered blasphemous.

They also took it as a threat.

It is likely that such opinions were not those of the majority of Northerners, but they were certainly read with a growing animosity in the South toward their Northern countrymen. Southern Fire Eaters — those who had been advocating for secession for some time — used the Northern reaction by newspaper editorials and intellectuals in the North to ramp up their calls for separation from the North. Clearly, John Brown was an “instrument” to be used by radicals on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line.

In only a year, South Carolina would lead the way in seceding from the federal Union, followed by six other states in the Deep South. Four more border states joined them when President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress what he called the “rebellion” in those 10 states. The refusal of President Lincoln to allow for a peaceful secession then led then to a war that took at least 600,000 — and probably more — lives in the bloodiest war in American history.

Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry was a huge failure militarily, but it no doubt advanced his cause — and the cause of the New England conspirators who aided him financially.

The lesson of John Brown, in light of modern violent protesters who invoke his name, is clear: Violence committed in the name of a cause, backed by powerful people, can cause a reaction that will further advance that cause. This was true in Brown’s day and is true in our own.

Brown’s violent tactics accomplished little but the slaughter of innocents along with the guilty. Today, violent protesters want to provoke an overreaction from the police, or the National Guard. Deaths of modern John Browns are part of the price to be paid, along with innocent bystanders, in the radical cause.

And that is the lethal legacy of John Brown.

This article is an example of the exclusive content that's available by subscribing to our print magazine.