Although rocked by antigovernment protests that have resulted in the deaths of several people and the imprisonment of many others, Venezuela remains in the grip of its highly unpopular president, Nicolás Maduro, and his disastrous socialist policies. Ironically, these policies may also be the one thing keeping Maduro in power.

The latest wave of protests is largely in response to political repression. The country’s Supreme Court essentially dissolved the legislature, the only branch of the government not controlled by Maduro allies, on March 29. The court, at Maduro’s urging, reversed the ruling three days later after a major international outcry. Then, on April 7, the government banned opposition leader Henrique Capriles from public office for the next 15 years, though Capriles, a two-time presidential candidate, vowed to remain in his post as governor of Miranda state.

Opposition forces call Maduro a tyrant and dictator, pointing to, among other things, his repeatedly delaying elections and blocking a referendum that could remove him from office. He, in turn, refers to them as “vandals and terrorists.”

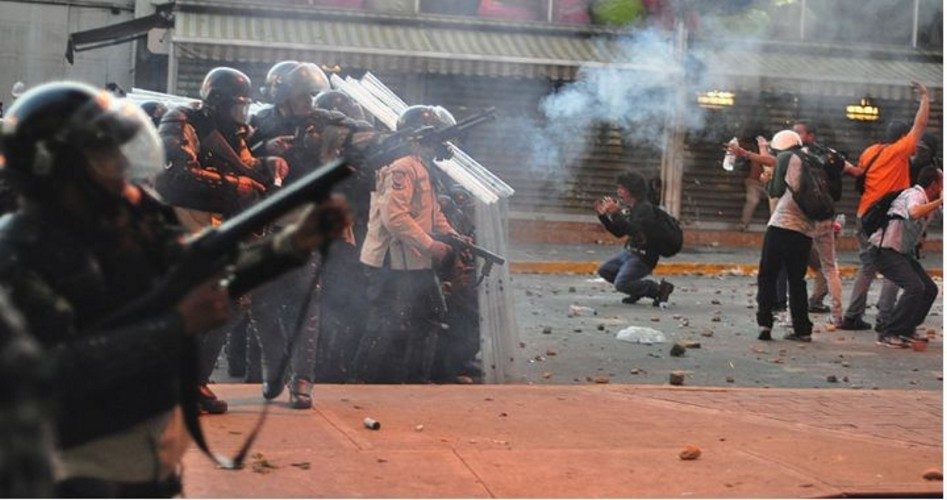

On Wednesday and Thursday, reported CNN, “protesters started their march at 26 different points throughout Caracas and converged at the office of the ombudsman, the government’s top human rights official.” The government and its supporters responded with “water cannons and tear gas canisters.” At least three people were killed during Wednesday’s protests, bringing the total deaths over the last three weeks to seven.

While Maduro’s political opponents are busy protesting his heavy-handed rule, however, the vast majority of Venezuelans are simply trying to get by in an economy devastated by socialism. The inflation rate reached 800 percent in January, unemployment is on its way to 25 percent, and food and medicine are in short supply and often too expensive for the average person. Some poor Venezuelans have taken to eating garbage, stray cats and dogs, and even flamingos and anteaters to avoid starvation. The average Venezuelan lost 19 pounds last year, according to a study by three leading Venezuelan universities.

The threat of starvation, coupled with the government’s control of the food supply, may be the ace up Maduro’s sleeve, reported the Wall Street Journal. Although “almost two-thirds of Venezuela’s poor … want Mr. Maduro to leave,” the paper wrote, political protest “remains mostly confined to middle-class enclaves” because the poor are too hungry and dependent on the government to rise up against it.

“All I have is hunger — I don’t care if the people protest or not,” laborer Alfonzo Molero, in a slum in Venezuela’s second-largest city, Maracaibo, told the Journal. “With what strength will I protest if my stomach is empty since yesterday?”

In addition, since the only source of food is government handouts, many poor people keep their opinions to themselves for fear of being denied sustenance. “We wear our protest on the inside for the fear of losing our bag of food,” said San Félix resident Luisa Gutiérrez, a single mother of three.

Even “radical opponents” of Maduro hold their tongues when it comes time for food distribution, the Journal noted. After all, one dare not bite the hand that feeds him — one reason among many that socialism is detrimental to liberty.

There is also, observed the paper, the matter of “armed pro-government militias who scour the slums for signs of dissent,” not to mention the fact that few of Venezuela’s poor have access to news outside the state-controlled media. Thus, not many of them know the times and place of protests, and even those who do are often afraid to join them because the “mostly peaceful protestors” are portrayed as “Molotov-cocktail-throwing ‘terrorists.’”

Furthermore, the protestors’ and slum-dwellers’ differing objectives tend to keep the two groups from cooperating. Wrote the Journal:

The opposition’s rallying cry centers on political rights like freeing political prisoners and holding elections, rather than on bread-and-butter issues such as food prices and scarcity.

“We, the politicians and activists[,] are not thinking like these people,” said Jhovant Landaeta, an opposition activist in the impoverished Valles del Tuy region outside Caracas. “They’re isolated from the national debate.”

Without support in the shantytowns, many opposition supporters fear the current protests will end like the previous wave of unrest in 2014, when three months of demonstrations in middle-class neighborhoods left 43 people dead — without achieving any political change.

Things may have to get worse in Venezuela before they get better. The poor will need to feel they have nothing to lose by challenging the government, and the official opposition will need to swallow its pride — the Journal reported that its “predominately upper-middle-class leaders have ignored the slums for years” — and begin taking the lower classes’ concerns seriously.

Deteriorating conditions are, in fact, almost a certainty, given Maduro’s policies and personality. The socialism that brought him to power and is now keeping him there will likely lead to his downfall. The only question is how much longer his people will have to suffer before that happens.

Photo of protesting in Venezuela from 2014: Andrés E. Azpúrua Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported