In the face of ongoing political pressure from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, the President of Iceland has once again asserted the right of the Icelandic people to defend their nation from foreign financial schemes which would devastate their economy for a generation.

As was reported for The New American previously, the crisis in Iceland was in many ways a summary of the economic crisis which shook the globe in 2008; however, the situation was far worse for a relatively defenseless nation, which soon found itself prey to financial interests that were unwilling to suffer a loss on their investments, and were prepared to contort post-“9/11” legislation to coerce Icelanders to pay a “debt” which they contended they did not owe. As was reported for The New American in January 2010:

As Iceland’s economy began to collapse, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown exploited “anti-terrorism” laws to seize Icelandic assets, and thus put pressure on the tiny nation of roughly 300,000 to pay for an exorbitant bailout for losses on investments in Icelandic banks. The new Icelandic government pushed for membership in the European Union as part of the supposed cure for Iceland’s financial woes, and prepared to sacrifice the country’s financial future through a commitment to capitulate to Brown’s demands.

The pressure to submit to the yoke of EU membership — and the concurrent submission to Brown’s demands — developed within the Icelandic parliament because in the 2008 Icelandic elections, as in the United States, leftwing politicians took advantage of economic woes to win power and immediately began to implement an internationalist agenda which outraged the electorate. In short, a majority of Icelanders had cast votes based on their fears and a desire to punish a political party which they held responsible for their troubles, but they soon discovered that the plans of Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir and her coalition members would make a bad situation even worse. The financial “shakedown” became a means for the prime minister and her allies to try pushing for full membership in the EU, at the cost of assuming a financial burden exceeding the capacity of such a small nation to ever repay.

The leftwing agenda soon met stiff resistance from the Icelandic people. As Reuters reported over a year ago:

Nearly a quarter of Icelandic voters have signed a petition asking their president to veto a bill on repaying $5 billion lost by British and Dutch savers when the island’s banks collapsed, organizers said on Saturday.

The petition also called on President Olaf Ragnar Grimsson to call a referendum on an issue which has aroused resentment that taxpayers are being left to pay for banks’ mistakes.Earlier this week parliament approved the amended bill to reimburse Britain and the Netherlands for the amount, which was lost by savers in both countries in 2008 who deposited funds in high-interest “Icesave” online savings accounts.

But the president has yet to sign the bill into law and 56,089 people, who represent 23 percent of the island nation’s electorate, have signed the petition, the organizers said.”I consider it to be a reasonable demand that the economic burden placed on the current and future generations of Icelanders, in the form of a state guarantee for Icesave payments to the UK and Dutch governments, be subject to a national referendum,” the text of the petition read.

InDefence, the group responsible for gathering the signatures, said the Icesave legislation represented a “huge risk” for Iceland’s economic future.

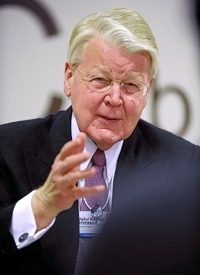

President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson (photo above) announced on February 20 of this year that he will veto the latest version of the Icesave legislation; according to IcelandReview.com, he desires that the entire nation vote on the proposal:

President of Iceland Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson just announced in a press conference that he will not sign the new Icesave legislation but instead send it to a national referendum. He reasoned that the majority of the nation wants to vote on the legislation as indicated in recent polls.

The president also mentioned that only a slight majority of MPs voted against a referendum on Icesave in parliament when the new Icesave legislation was passed last week and that a large proportion of voters had signed a petition urging him to make this move.

It is difficult to overstate the devastating effect which Icesave would have had on Iceland; only a few weeks ago, InDefence declared in a press release:

Iceland’s population is 317,000, the size of Cardiff and Utrecht. The UK and Netherlands are claiming reimbursement for payments of €3.9bn (£3.4bn or ISK715bn) to Icesave depositors of the failed private Landsbanki Bank. This is not an Icelandic debt – it is a forced obligation without any consideration of economic safeguards. The upfront amount is 50% of Iceland’s GDP, equivalent to £700bn for the UK or €270bn for the Netherlands. Iceland’s foreign debt is already 310% of GDP according to the IMF. The obligation represents €48,000 (£40,000 or ISK8.9m) per Icelandic family. The added annual interest per family is €2,600 (£2,200 or ISK460,000) even with full recovery of Landsbanki assets. The UK, Netherlands and EU must share responsibility with Iceland for the failed financial supervision of cross-border banking. …

Icesave is not Icelandic debt. Iceland adhered to a flawed EU deposit guarantee directive, which did not address a complete collapse of a local banking sector as in Iceland. The UK and Netherlands demand a state guarantee of Icesave deposits, but there is no mention of a state guarantee in the EU directive. The UK, Netherlands and EU must share responsibility for failed financial supervision of cross-border banking.

The Icesave legislation will now come before the Icelandic people at the polls on March 6. If a burden of €48,000 (approximately $65,600) per family is going to being assumed, it will only be after the people who will bear this burden have had an opportunity to actually vote on the bailout. Whether or not the Icelanders choose to capitulate to foreign pressure and adopt Icesave, the bailout decision will not simply be imposed upon them by one faction of the political class.

Photo: Iceland’s President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson