The Socialist government of Greece has announced an austerity program that freezes pensions, cuts the salary of civil service employees, and increases taxes as a way of restoring confidence in the ability of Greece to meet its financial obligations. The government of this Mediterranean nation suffers from the same sort of extravagant spending and imprudent long-term obligations that have wreaked havoc in other European nations like Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Iceland. The actions of the Greek government have not worked.

The servicing of the Greek government debt has spiked because of this lack of confidence by investors in bonds, which is translating into increasingly higher interest rates on the bonds. The vicious cycle of borrowing more and more money simply to pay existing debt has pushed the interest rate on Greek long term bonds 4.48 points higher than German long-term bonds, which is considered the benchmark in Europe.

The Greek national deficit had been projected to equal 12.9 percent of the GDP of Greece, and the austerity program was anticipated to reduce that deficit to 8.7 percent of the GDP. The skittishness of the bond market, however, indicates a lack of faith that the changes would produce the necessary reduction in government debt. The European Central Bank has taken the position that a default on outstanding bonds is “not an issue.” Beat Siegnthaler, a currency strategist at UBS, however believes that there is little doubt that the government of Greece will have to turn to the International Monetary Fund for help. He noted that companies and individuals have been pulling their money out of accounts in Greece.

European officials have been cautious about saying exactly what actions would be taken to avoid a default by the Greek government. The IMF could loan money only if all 16 of the eurozone members agreed. Germany, however, had indicated that it would not agree to an IMF bailout. Even if the German government decided to permit such a loan, the nations of the eurozone have been very guarded regarding the interest rates that would be charged to the Greek government, noting only that the rates would have to be higher than the average rates charged to “set incentives to return to market financing as soon as possible.”

What happens in Greece will be a strong indicator of what will happen if other governments in Europe reach a point of possible default on bonds. The Socialist government of Spain, which is facing a serious crisis as well, has begun to blame the “Anglo-Saxon media” for trying to undermine confidence in the Spanish economy. Spain has just ended seven consecutive quarters of negative growth and it has the highest unemployment in the European Union, which resulted in its government bonds being reduced from “stable” to “negative,” which will push up the interest that Spain will have to pay to service its debt.

Iceland, at the opposite corner of Europe from Greece, faces a financial crisis which has led many Icelanders to simply want to withdraw from the international financial system. Icelanders have expressed resentment toward British and Dutch governments, similar to the resentment that the Spanish and Greeks have felt toward governments with more stable bond ratings. International organizations and the much hailed “interdependence” of economies and governance, once thought the panacea for all ills, seems to be failing badly and with it creating latent anger and blame among nations.

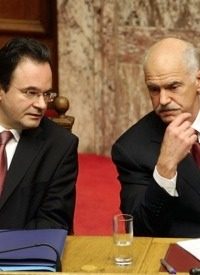

Photo: Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, right, and Greek Finance Minister George Papaconstantinou in Athens on March 22: AP Images

Related content: