The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has now admitted that it accessed 33 million mobile devices (in a country of 38 million people) to monitor citizens’ movement amid the lockdown.

“Due to the urgency of the pandemic, (PHAC) collected and used mobility data, such as cell-tower location data, throughout the COVID-19 response,” a PHAC spokesperson told The National Post. The program’s existence was first made widely known by a report from Blacklock’s Reporter.

PHAC said it used the data to determine the effectiveness of public lockdown protocols and allow the Agency to “understand possible links between movement of populations within Canada and spread of COVID-19.”

The agency in March awarded a contract to the Telus Data For Good program to provide “de-identified and aggregated data” of movement trends in Canada. According to the PHAC spokesperson, the contract expired in October and PHAC no longer has access to the location data.

Yet the Agency still has plans to track public movement over the course of the next five years for the purpose of addressing other public health issues, such as “other infectious diseases, chronic disease prevention and mental health.”

Privacy advocates raised concerns about how the program might affect Canadians’ rights in the long-term.

“I think that the Canadian public will find out about many other such unauthorized surveillance initiatives before the pandemic is over — and afterwards,” David Lyon, author of Pandemic Surveillance and former director of the Surveillance Studies Centre at Queen’s University, told National Post in an email.

Lyon warned that PHAC “uses the same kinds of ‘reassuring’ language as national security agencies use, for instance not mentioning possibilities for re-identifying data that has been ‘de-identified.’”

“In principle, of course, cell data can be used for tracking.”

The PHAC spokesperson argued that mobility data analysis “helps to advance public health objectives,” the PHAC spokesperson said. The findings have been regularly shared with provinces and territories via the special advisory committee to “inform public health messaging, planning and policy development.”

The data is also used for the COVID Trends portal, a dashboard that compiles summarized information about movement.

Lyon urged a need for greater information “regarding exactly what was done, what was achieved and whether or not it truly served the interests of Canadian citizens.”

Martin French, an associate professor of Concordia University focusing on surveillance, critiqued PHAC’s program from the Left, warning that it could have dire consequences for “equity.”

“There are populations that could experience an intensification of tracking that could have harmful (rather than beneficial) repercussions,” French wrote.

Lyon further contended that COVID-19 has created a new normal of sacrificing privacy for security’s sake.

“The pandemic has created opportunities for a massive surveillance surge on many levels—not only for public health, but also for monitoring those working, shopping and learning from home,” he said, adding:

“Evidence is coming in from many sources, from countries around the world, that what was seen as a huge surveillance surge—post 9/11—is now completely upstaged by pandemic surveillance.”

The National Post noted:

In a notice posted earlier this week, the agency called for contractors with access to “cell-tower/operator location data in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and for other public health applications.” It asks for “de-identified cell-tower based location data from across Canada” beginning from from Jan. 2019 until the end of the contract period on May 31, 2023, with possibility of three one-year extensions.

The contractor must provide anonymized data to PHAC and ensure its users have the ability to easily opt-out of mobility data sharing programs, the agency says.

PHAC’s privacy management division conducted an assessment and “determined that since no personal information is being acquired through this contract, there are no concerns under the Privacy Act,” the spokesperson said.

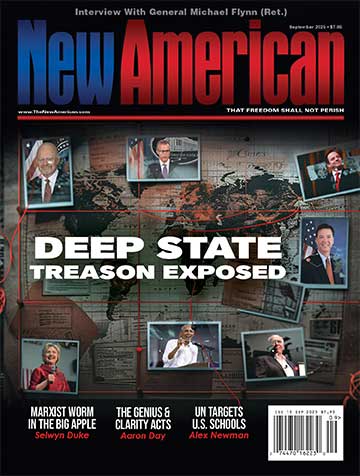

As The New American’s Alex Newman has reported, “contact-tracing” schemes in the United States are connected to the Clintons and George Soros.

“Dimagi, for instance, which is working with authorities across the United States and beyond, uses an app based on WHO protocols to track everyone. It boasts that its ‘partners’ include the Gates Foundation, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the World Bank,” Newman wrote.

Governments claim such invasions of privacy are merely for the purpose of “data analysis,” but in a world in which medical discrimination is now becoming the norm, your location data is the last thing you want the government to possess.