Is the United States bankrolling its own enemies in Afghanistan? According to a new report from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), the answer may very well be yes. “Since 2002,” the report opens, “Congress has appropriated more than $70 billion to implement security and development assistance projects in Afghanistan, with some of those funds converted into cash and flowing through the Afghan economy.” But where has that cash gone? No one in the U.S. government knows for sure, and the Afghan government of President Hamid Karzai seems none too eager to assist Washington in finding out.

One problem from the American side, SIGAR says, is the perennial difficulty of getting multiple government agencies to cooperate with one another. Because, for instance, the Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security “have not coordinated their efforts involving work with the same banks,” the report explains, “these agencies are at a risk of working at cross purposes, or, at a minimum, missing opportunities to leverage existing relationships and programs.”

From the Afghan side, Karzai’s government has, in general, been less than helpful in rooting out financial corruption, SIGAR reports. For one thing, “the Afghan Attorney General’s office has not cooperated fully in prosecuting individuals suspected of financial crimes,” following up on only four of 21 leads provided by U.S. officials. For another, Karzai has personally prevented U.S. advisers from working at DAB. The Afghan government has also refused to permit an independent audit of Afghanistan’s largest commercial bank, Kabul Bank, which was nearly brought down by a fraud and corruption scandal in 2010. The fact that Kabul Bank is used by the government to pay as many as 300,000 military and security forces may have something to do with it.

At Kabul International Airport the situation has been little better, the report says. First the installation of bulk currency counters was delayed because of a dispute between the U.S. and Afghan governments. Then, when the machines were installed, “Afghan customs officials were using the machines to count declared cash, but not to record serial numbers or report financial data to” U.S. officials. VIPs, as designated by the Afghan government, are able to “bypass the main security and customs screenings used by all other passengers” and do not have their currency counted. Then there is the matter of signs: Though Afghan officials agreed to post signs at the airport telling passengers that they must declare cash totaling $22,000 or more before leaving the country, there was an eight-month delay in getting those officials to agree on where to place the signs — and when they finally did decide on placement, the signs were installed in locations such that “passengers are not informed of the requirement to declare their currency until it is too late.”

The point of all this counting of cash is to ensure that U.S. payments are not being diverted to insurgent or terrorist groups or smuggled out of Afghanistan. SIGAR refers to “reports of as much as $10 million a day in cash leaving the Kabul International Airport.”

The Afghans aren’t the only ones to blame for this situation; U.S. agencies have not been models of tracking payments, either. SIGAR points out “three vulnerabilities that could allow U.S. funds to be diverted for improper uses”:

First, U.S. agencies do not record the serial numbers of cash disbursed to contractors and other recipients of U.S. funds. Second, commercial banks do not record the serial numbers of EFT [Electronic Funds Transfer] payments made by U.S. agencies to contractors and other recipients when they are monetized. Third, U.S. contracting regulations neither prohibit prime contractors from using unlicensed hawalas [informal banking networks] to pay subcontractors nor require prime contractors to use EFT-capable banks to make payments. Therefore, the United States is unable to record information on these funds when they enter Afghanistan’s economy and the Afghan and U.S. governments are unable to track them as they move from person to person.

In short, neither the Americans nor the Afghans know where American taxpayer dollars are going once they leave Washington’s wallet. “As a result,” the report concludes, “the U.S. risks inadvertently funding activities that directly oppose its reconstruction goals for Afghanistan.”

This is nothing new, of course. Government programs routinely achieve the opposite of their stated objectives. Nor is it the first time such a report has come out of Afghanistan. A December SIGAR report found that U.S. agencies were “unable to readily report on how much money they spend on contracting for reconstruction activities in Afghanistan.” “Similarly,” writes John Glaser of Antiwar.com, “the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Democratic majority staff last month concluded that U.S. nation-building efforts were fueling corruption, distorting local economies, and did not provide sustainable results.”

“The U.S. effort in Afghanistan lacks a coherent military strategy, comes at a painfully high human cost, and is as full of waste and corruption as the Afghan government itself,” Glaser concludes. “The pretense, forced upon the Afghan people for the last decade, that America knows best how to build a sustainable, legitimate nation consistent with the rule of law is simply not borne out by these revelations.”

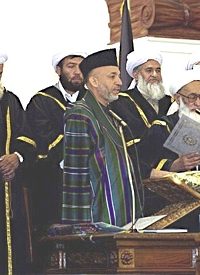

Photo: Hamid Karzai standing next to Faisal Ahmad Shinwari and others after winning the 2004 presidential election.