Reuters reported that soon after the third nuclear test conducted by the communist government of North Korea on February 12, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon condemned the test, saying it was “deplorable” that Pyongyang had defied international appeals to refrain from such provocative acts.

“The Secretary-General condemns the underground nuclear weapon test conducted by (North Korea) today,” Ban’s spokesman Martin Nesirky said in a statement made on the 12th. “It is a clear and grave violation of the relevant Security Council resolutions.”

In an emergency session on February 12, the Security Council unanimously said the nuclear test poses “a clear threat to international peace and security” and pledged further action, reported Fox News. However, China, as a member of the Security Council, holds veto power over the imposition of sanctions on North Korea and it is uncertain as to whether China will use its veto to protect its ally.

In the February 12 nuclear test, North Korea exploded a device reported to be twice as powerful, yet smaller in size, than its last nuclear test on May 25, 2009. Following the 2009 test, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1874, condemning the test and tightening sanctions on the country.

North Korea’s first such test was conducted on October 9, 2006. All three weapons were detonated underground, and theoretically meet the criteria established by the Limited (or Partial) Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which banned all nuclear tests except for those performed underground. (That treaty was initially singed by the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. North Korea has never acceded to or ratified that treaty, though 126 other states have.)

BBC News reported that the Pyongyang government described the test as a “self-defensive measure” necessitated by the “continued hostility” of the United States, and noted that China, considered to be North Korea’s principle ally, was among the nations that criticized the test.

The BBC report cited the opinion of unnamed analysts who said that the smaller size of this device could bring Pyongyang closer to building a warhead small enough to be carried on a missile.

North Korea’s official KCNA news agency announced the test with the following statement:

It was confirmed that the nuclear test, that was carried out at a high level in a safe and perfect manner using a miniaturized and lighter nuclear device with greater explosive force than previously, did not pose any negative impact on the surrounding ecological environment.

President Obama made reference to the North Korean action in his State of the Union address delivered the evening after the test:

Of course, our challenges don’t end with al Qaeda. America will continue to lead the effort to prevent the spread of the world’s most dangerous weapons. The regime in North Korea must know that they will only achieve security and prosperity by meeting their international obligations. Provocations of the sort we saw last night will only isolate them further, as we stand by our allies, strengthen our own missile defense, and lead the world in taking firm action in response to these threats. [Emphasis added.]

Fox News reported that the new U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, issued a statement to reporters at the State Department following a meeting with Jordanian Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh, in which he said that the world’s nations must agree on a “swift, clear, strong and credible response” to North Korea’s third nuclear test and the regime’s “continued flaunting of its obligations.” (Emphasis added.)

The use of the word “obligations” by both Obama and Kerry continues a pattern of using language that diminishes the national sovereignty of countries (however autocratic or tyrannical their leaders may be) by unilaterally imposing conditions upon them that they never agreed to.

Those who favor an internationalist approach settling disputes among nations often define “obligations” as mandates that are imposed on nations and enforced by a broad authority called the “international community,” generally meaning members of the UN or one of its many subsidiary agencies.

For example, on June 9, 2010, President Obama made a statement commenting on the UN Security Council’s vote earlier in the day to impose a fourth round of sanctions against Iran in response to that nation’s controversial nuclear-fuel enrichment program.

This resolution will put in place the toughest sanctions ever faced by the Iranian government,” said the President, “and it sends an unmistakable message about the international community’s commitment to stopping the spread of nuclear weapons.” [Emphasis added.]

Obama continued, employing the terms “obligations” or “international community” several times:

For years, the Iranian government has failed to live up to its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It has violated its commitments to the International Atomic Energy Agency. It has ignored U.N. Security Council resolutions. And while Iran’s leaders hide behind outlandish rhetoric, their actions have been deeply troubling. Indeed, when I took office just over 16 months ago, Iranian intransigence was well-established. Iran had gone from zero centrifuges spinning to several thousand, and the international community was divided about how to move forward….

We made clear from the beginning of my administration that the United States was prepared to pursue diplomatic solutions to address the concerns over Iranian nuclear programs. I extended the offer of engagement on the basis of mutual interest and mutual respect. And together with the United Kingdom, with Russia, China, and Germany, we sat down with our Iranian counterparts. We offered the opportunity of a better relationship between Iran and the international community — one that reduced Iran’s political isolation, and increased its economic integration with the rest of the world. In short, we offered the Iranian government the prospect of a better future for its people, if — and only if — it lives up to its international obligations. [Emphases added.]

By appealing to the “international community” (the UN) to control nuclear weapons, Obama and Kerry — the latter a member of the internationalist Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) — are following in the footsteps of one of their Democrat predecessors in the White House, John F. Kennedy (also a CFR member), who on September 25, 1961, presented to the 16th General Assembly of the United Nations a disarmament proposal entitled Freedom from War: The United States Program for General and Complete Disarmament in a Peaceful World (State Department Publication 7277). One of the planks of that documents called for “progressive controlled disarmament and continuously developing principles and procedures of international law [that] would proceed to a point where no state would have the military power to challenge the progressively strengthened U.N. Peace Force and all international disputes would be settled according to the agreed principles of international conduct.”

The language employed in that document and Obama’s recent statements are both replete with references to “international” law and obligations, as if national sovereignty were of no consequence.

Also reading from the same script was U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, who told a Pentagon news conference: “It should be of great concern to the international community that [the North Koreans] are continuing to develop their capabilities to threaten the security, not only of South Korea, but of the rest of the world. And for that reason, I think that we have to take steps to make very clear to them that that kind of behavior is unacceptable.”

Opponents of internationalism (the polar opposite of national sovereignty) have repeatedly warned that by ceding authority to an international authority answerable to the UN, in order to put recalcitrant “rogue” states in their place, the United States and other Western nations will likely diminish their own sovereignty to the extent that the UN will someday be able to impose its authority over us.

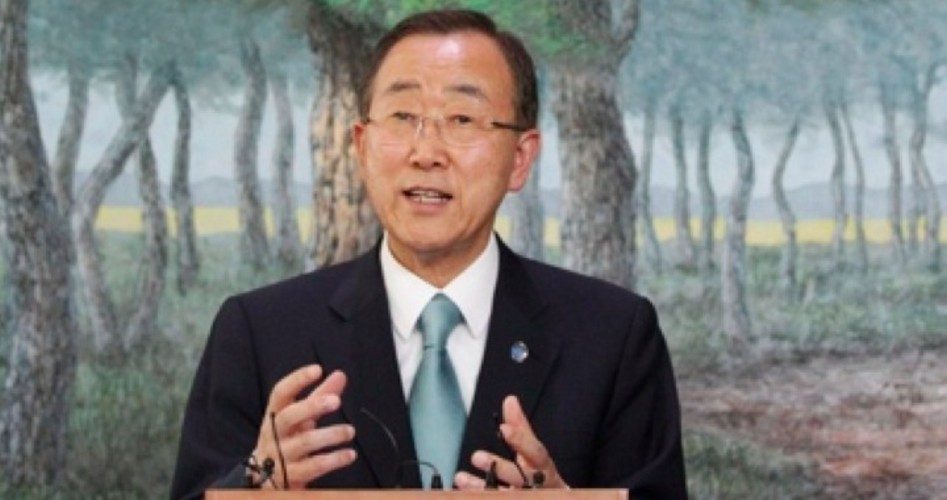

Photo of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon: AP Images