On September 12, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem sent a letter to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) — which describes itself as “the implementing body of the Chemical Weapons Convention” (CWC) — informing the international body that it intends to join the CWC and that Syria is in the process of transmitting its “legislative decrees to the UN Secretary General.”

A report posted on the OPCW website stated that the director-general of the organization, Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, informed Muallem that Syria’s request for “provisional application of the Convention” (a step made prior to formal entry into the OPCW) has been forwarded to the States Parties to the CWC for their consideration.

Information posted by the OPCW states that the Chemical Weapons Convention came into being when the UN-linked Conference on Disarmament adopted its draft text on September 3, 1992 and sent it to the UN General Assembly. The General Assembly approved it that December and instructed that it be opened for signatures in Paris, starting on January 13, 1993. When 130 states signed the Convention within the first two days, it was deposited with the UN secretary-general in New York. There is a distinction between signing and ratification, however. (For example, a U.S. president or ambassador may sign a treaty, but it must be approved by the Senate to be declared ratified.) According to the terms of the Convention, the CWC would enter into force 180 days after the 65th country ratified the treaty. Hungary became the 65th country to ratify the Convention, in late 1996, and on April 29, 1997 the Chemical Weapons Convention entered into force with 87 States. The United States is an OPCW member state, having signed the Convention on January 13, 1993. The Senate voted 74-26 on April 24, 1997 to approve the Convention.

Removing any doubt that the OPCW is under the UN umbrella, the OPCW notes: “The Relationship Agreement between the United Nations and the OPCW was concluded with the United Nations in 2000 and entered into force in 2001.” Furthermore: “The United Nations recognises the OPCW as the organisation, in relationship to the United Nations as specified in this agreement, responsible for activities to achieve the comprehensive prohibition of chemical weapons in accordance with the Convention.”

The OPCW currently has 189 member states, with Israel and Myanmar having signed the treaty but not ratifying it, and Angola, Egypt, North Korea, South Sudan, and (until now) Syria never having signed.

The Irish Times reported that Secretary of State John Kerry yesterday began talks in Geneva with Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, discussing a plan to secure and dispose of Syria’s chemical weapon supply.

Syrian President Assad has said that Damascus is prepared to place its chemical weapons under international control, insisting “the U.S. threats did not influence our decision,” reported the Times.

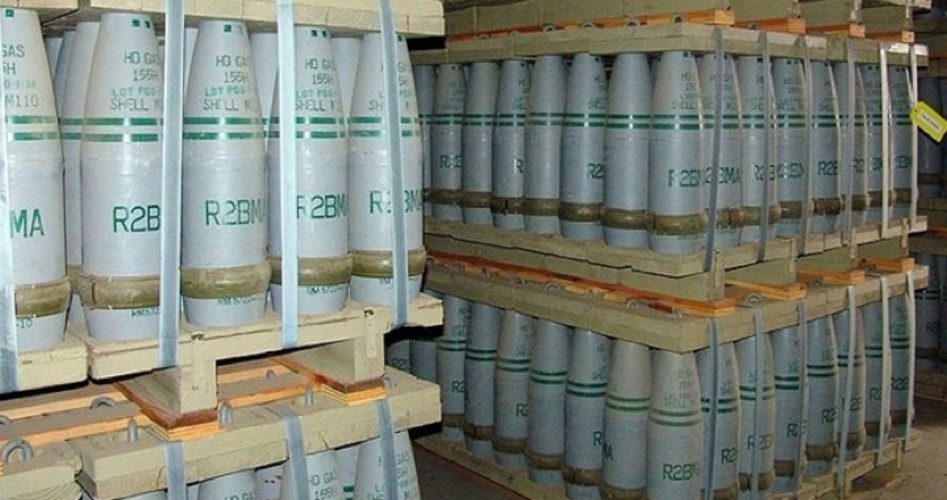

Under the plan first proposed by Russia, Syria would join the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, reveal sites where its chemical weapons are stored and manufactured, allow inspectors from the organization to examine them, and make arrangements with the inspectors to destroy the weapons.

CBS News reported that Syria’s UN ambassador, Bashar Ja’afari, told reporters on September 12 that he has presented UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon with “the instrument of accession” to the Chemical Weapons Convention, which he asserts makes Syria a full member of the treaty banning the use of chemical weapons.

Such a statement may be premature, however. CBS News cites UN associate spokesman Farhan Haq, who said that while the secretary-general welcomes Syria’s step, the Middle East nation will not become a member of OPCW until 30 days after its instrument of accession is deposited, stating that the documentation is still being studied.

Assad made a statement on Russia’s state Rossiya 24 news channel on Thursday in which he credited Russia’s influence in influencing him to submit to international controls. “We agreed to put Syria’s chemical weapons under international supervision in response to Russia’s request and not because of American threats,” said Assad.

“In my view, the agreement will begin to take effect a month after its signing, and Syria will begin turning over to international organizations data about its chemical weapons,” Assad added. He said this is “standard procedure” and that Syria will stick to it, noted CBS.

Assad also said: “We are counting, first of all, on the United States [to] stop conducting the policy of threats regarding Syria.”

In a statement made on pan-Arab satellite channels, reported CBS, Gen. Salim Idris, the top commander of the rebel forces calling themselves the Free Syrian Army, who are fighting against the Assad government, said: “We call upon the international community, not only to withdraw the chemical weapons that were the tool of the crime, but to hold accountable those who committed the crime in front of the International Criminal Court.”

Idris added that the Free Syrian Army “categorically rejects the Russian initiative” as not meeting the demands of the rebel fighters.

Reuters news also noted the differences in statements emanating from Syrian and UN officials about whether Syria is yet a member of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

While Syrian UN Ambassador Bashar Ja’afari told reporters in New York on September 12, “Legally speaking Syria has become, starting today, a full member of the (chemical weapons) convention,” Erin Pelton, spokeswoman for the U.S. mission to the United Nations, had a different view of Syria’s status in the process to become a full-fledged OPCW member. She said that Syria’s declared intention to join the OPCW was just a first step.

“This long overdue step does not address the pressing and immediate need for a mechanism to identify, verify, secure and ultimately destroy Assad’s chemical weapons stockpile so they can never again be used,” Pelton said. “It also does not include immediate consequences for non-compliance.” Added Pelton: “The international community must insist on immediate progress toward destruction of Syria’s CW (chemical weapons) program and also make clear that there will be consequences for any Syrian noncompliance.”

What is clear amidst the various exchanges between the Syrian government and its adversaries is that this crisis — like all recent conflicts in the Middle East — has increased the status of the UN.

Following Russia’s recommendations, Syria has applied for membership in a UN-linked organization in order to forestall a U.S. attack. The rebel commander has called for Syrian government officials to be tried before the UN-controlled International Criminal Court. And in his statement released on August 21, President Obama’s Deputy Press Secretary Josh Earnest said: “Today, we are formally requesting that the United Nations urgently investigate this new allegation [of the use of chemical weapons].”

It might be well to recall that the stage was set for constant turmoil in the Middle East when the Ottoman Empire, an ally of Germany, was defeated in World War I. Following that war, the League of Nations (the predecessor to the UN) issued mandates to determine the fate of former Ottoman territory. Among these was the mandate for Syria (which then included Lebanon) under which France was charged with administering the territory, which it did from 1923 to 1944.

As has happened elsewhere in the world, when colonial powers drew borders that ignored historic tribal and ethnic rivalries, chaos resulted. It is unlikely that such chaos can be resolved by giving more power over Middle Eastern affairs to the League’s successor, the UN.