With the choice of Mohamed Morsi as Egypt’s first freely elected president since the birth of the Egyptian Republic in 1953, the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood is moving to consolidate its control of the country. The presidential election came down to a choice between the militant Islamist ideology of Morsi and Ahmed Shafik, the man perceived to represent the interests of the military forces that have ruled the republic since it was first declared.

Egypt has been undergoing a transition since the “Arab Spring” uprising in early 2011 toppled the government of President Hosni Mubarak. The events in Egypt, in turn, led to a wave of uprisings that have still not come to a conclusion; for example, Syria continues to suffer from the ongoing battle between the army of President Bashar al-Assad and rebel forces.

Throughout the 16 months that have passed since the downfall of the Mubarak government, the Egyptian military has overseen a process of “democratization” that has included free elections for the parliament and the presidency. Despite widespread rumors that the military was planning to renege on its promises, the process has continued. In the words of one anonymous official who spoke to Reuters:

“The military council has done its duty in keeping the election process free and fair, a true example of democracy, to the world,” said the official, who asked not to be named.

“The onus now is on the new president to unite the nation and create a true coalition of political and revolutionary forces to rebuild the country economically and politically.”

However, rebuilding a nation could easily prove to be vastly more difficult than tearing down the military government. As reported previously for The New American, even as the elections committee was preparing to declare Morsi the winner of the elections, thousands of his followers returned to Tahrir Square, denouncing “military rule.”

An Egyptian court has further limited the power of the military in the new government by determining that military forces may not arrest civilians. As Yasmine Saleh wrote for Reuters, the military had sought the power to make such arrests in the days leading up to the final vote in the presidential elections because supporters of Morsi were threatening to take to the streets if their candidate was not declared victor. However, the courts have overturned that military decision:

But rights groups and politicians challenged the decision, accusing the military of reviving emergency powers that stymied opposition to Hosni Mubarak until a popular uprising ended his three-decade rule in February last year.

On Tuesday, a court agreed with them.

“The court declares in its ruling that the Minister of Justice raped the authority bestowed by the constitution by issuing a decision to give members of the military police and military intelligence powers of arrest,” a document from the Cairo court explaining Judge Ali Fikry’s ruling read.

The Justice Ministry has the right to appeal the administrative court’s ruling, which is effective immediately.

The original decree restored the military’s mandate to enforce law and order before a new constitution is written — a process expected to last well beyond the July 1 date by which the ruling military council is due to hand power to president-elect Mohamed Mursi of the Muslim Brotherhood.…

“This ruling not only adheres to the constitution,” said Gamal Eid, a lawyer and rights activist. “It chimes with the current political climate because many people feel the military council is trying to suppress the civil direction in which the state is supposed to be heading.”

While Western governments may take such limitations on the intervention of the armed forced into domestic politics for granted, such has obviously not been the case in Egypt. The military sought the power to make arrests only days after a Mubarak-era emergency law expired — perhaps they imagined that the reassertion of such powers could pass unnoticed, or at least without such definitive opposition. In either case, the move was a serious miscalculation. As the Washington Post reported, human rights activists in Egypt recognize that the court action was a significant affirmation of basic liberty:

Heba Morayef, a Cairo-based researcher with Human Rights Watch, said Tuesday’s ruling might discourage the security forces from seeking to restore the type of vast, unchecked authority inherent in the old emergency law.

“This is a victory of a civilian court versus the kind of arbitrary expansion of military powers that would be a recipe for further abuses,” she said.

However, critics of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood raise questions about the commitment of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party to such high ideals: Only days before the runoff election, Islamists in the parliament sought to remove Shafik from the ballot — an action that would have preempted the election and almost certainly would have automatically made Morsi president of Egypt. Only an action of Egypt’s Supreme Constitutional Court was able to block the action of the parliament.

Now, with the election of Morsi, it appears that the Muslim Brotherhood will not be content merely to have beaten Shafik: The former candidate may have fled Egypt for fear of corruption charges. As reported by Ahram online, the charges followed in the immediate aftermath of the elections:

Less than 24 hours after Ahmed Shafiq lost the presidential contest to Mohamed Morsi, several lawyers have filed complaints with the office of the prosecutor against Mubarak’s last prime minister charging him with corruption.

A high-level judicial source said that councillor Osama El-Seidi, a Justice Ministry investigator, will receive this week the report prepared by experts in the Illicit Profiteering and Real Estate Agency who have examined procedures for the allocation of land sold by the Cooperative for Construction and Housing for Pilots, which was headed by Ahmed Shafiq in the 1990’s.

Former MP Essam Sultan of Al-Wasat Party issued a complaint against Shafiq as the former head of the cooperative, accusing him of selling a piece of land in the area of 40,238 square metres to Alaa and Gamal Mubarak in 1993, at an extremely low price of only 75 piasters per square metre.

Given that the alleged cases of corruption date back nearly 20 years, and that the charges came within hours of Shafik’s opponent attaining the presidency, critics could say that the Muslim Brotherhood is not even trying to give the appearance that the charges are anything other than political “payback.” When an organization that spent over 80 years as a “secret society” suddenly achieves political power, such tactics can hardly be surprising. As Frida Ghitis wrote for CNN.com:

For many years the Brotherhood was banned in Egypt, so it operated underground. Since the revolution, Egyptians have had a chance to see it in action. What they have seen so far is an organization impressively capable of modulating its message to suit specific audiences to achieve political gain.

More importantly, the Brotherhood has revealed a troublesome habit of breaking its word.

When Hosni Mubarak fell, they pledged they would not try to control Egyptian politics. But they promptly changed their minds.

The Muslim Brotherhood leaders promised to contest only a minority of seats in the legislature, rather than trying to win a majority. They broke that promise. They promised, through Morsi himself, “We will not have a presidential candidate. We are not seeking power.”

They broke that promise. They vowed to run a thoroughly inclusive process for developing a new Egyptian Constitution. They broke that promise, too.

Clearly, the Brotherhood, and the soon-to-be Egyptian president, have developed something of a credibility problem.

Since the Brotherhood has established such a track record in a mere 16 months, critics cannot help but ask how much time will transpire before those very powers that the military has been denied will be brought into the service of the reigning Islamists.

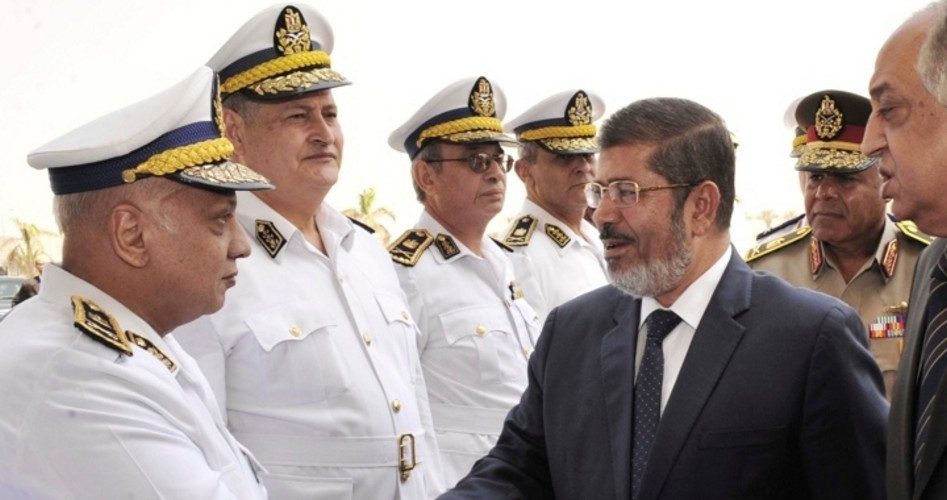

Photo: In this photo released by Middle East News Agency, the Egyptian official news agency, President-elect Mohammed Morsi shakes hands with an Egyptian police general in Cairo, Egypt, June 26, 2012. : AP Images