A proposed constitutional amendment by Senator Tom Udall (shown, D-N.M.) to give Congress the unlimited power to criminalize political speech has political roots that date back to the 1798 Sedition Act, as the senators promoting the current amendment are using virtually identical rhetoric to that of congressmen who advocated passage of the Sedition Act. The Udall amendment has been introduced in the wake of the 2010 Citizens United v. FEC Supreme Court decision, which increased anti-incumbent advertising by eliminating spending limits on independent political opinions by associations of citizens.

“Our government should be of, by and for the people — not bought and paid for by secret donors and special interests,” Senator Udall explained of his amendment April 30, adding, “I’m looking forward to working with Senator Schumer to bring common-sense campaign finance reform to a vote as soon as possible so we can ensure our elections are about the quality of ideas and not the quantity of cash.”

Udall’s amendment would “authorize Congress to regulate the raising and spending of money for federal political campaigns, including independent expenditures,” according to his U.S. Senate website. Translated from Washington-doubletalk, it means it would give Congress the legal power to censor any criticism of political incumbents — in effect, repealing the First Amendment.

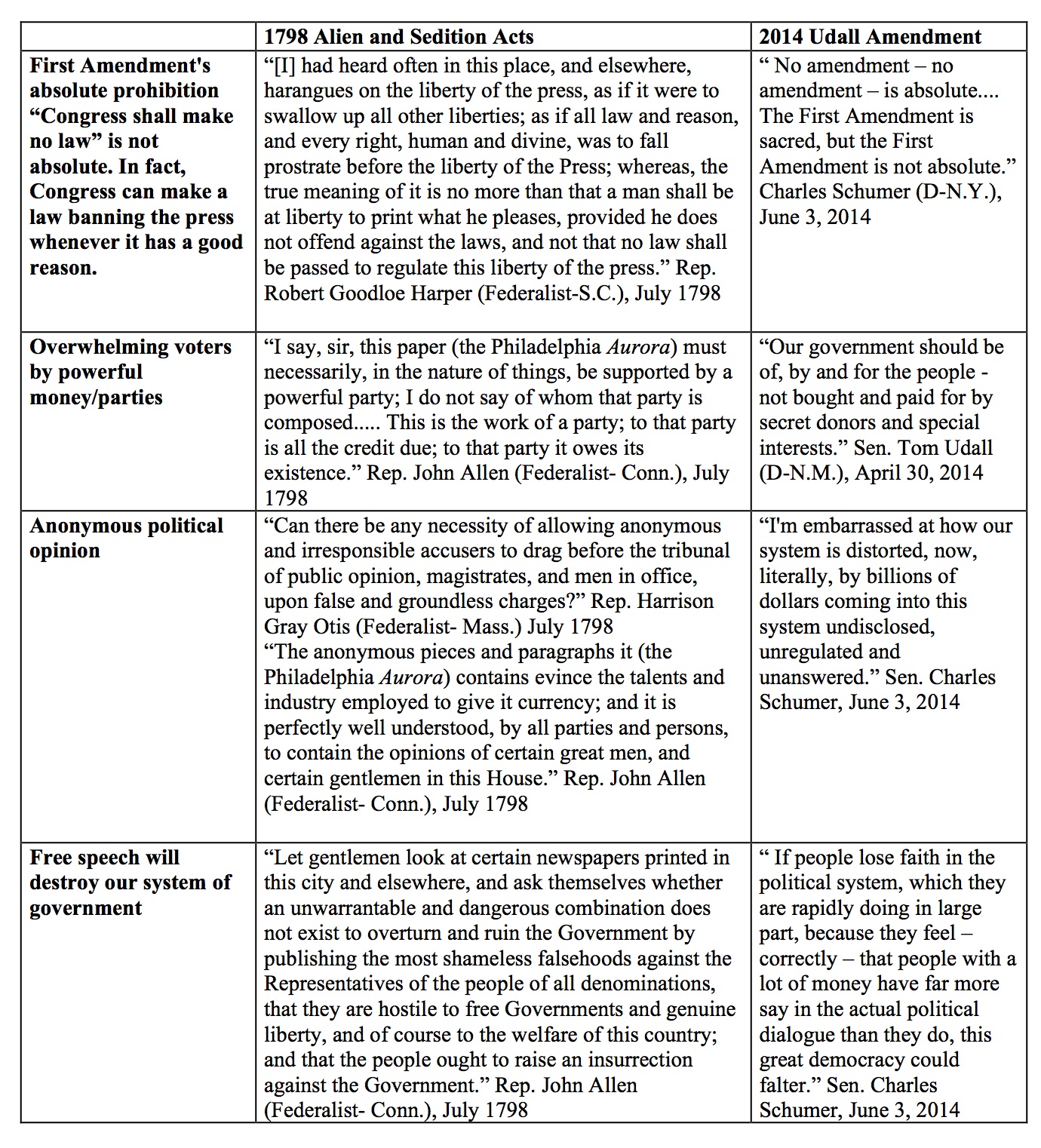

In order to sell the amendment, Udall retailed a litany of empty, fact-devoid slogans: “Elections have become more about the quantity of cash and less about the quality of ideas. More about special interests, and less about public service. We have a broken system based on a deeply flawed premise.” Indeed, proponents of the Udall amendment have employed virtually identical language to attack the First Amendment to that used during the Republic’s first attack on the freedoms of speech and press: the 1798 Sedition Act. Udall and his fellow Democratic Senators have argued that the First Amendment is not absolute, that the mass of propaganda against political officials is unprecedented and unsustainable, that an unleashed free press threatens our very system of government, and that anonymous political speech is dangerous to the political system. Each of these arguments were advanced by Federalist congressmen as reasons for passage of the 1798 Sedition Act:

In the end, the Sedition law was simply used by the Adams administration for putting his political opponents in the media in jail.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) argued in a June 3 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that “The American people reject the notion that money gives the Koch brothers, corporations or special interest groups a greater voice in government than American voters. They believe, as I do, that elections in our country should be decided by voters — those Americans who have a constitutional, fundamental right to elect their representatives. The Constitution doesn’t give corporations a vote, and it doesn’t give dollar bills a vote.”

But people who say that money is speech, that more money means more speech, and therefore more influence, go against human nature. Usually, the persons whose mouths talk the most — the loudmouths and chatterboxes — are the least influential in society. Senator Ted Cruz (R- Tex.) exploded Reid’s argument that money has no connection to free speech in the June 3 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing:

I do wish there were Democratic senators who were willing to defend the First Amendment…. The second canard that’s been put forth is money is not speech. That’s been repeated again and again in this hearing, and I would note any first-year law student who put that as his or her answer on an exam would receive an F, because it is obviously, demonstrably false and it has been false from the dawn of the republic. Speech is not just standing on a soapbox, screaming on the sidewalk. From the beginning of the republic, the expenditure of money has been integral to speech. The Supreme Court has said that pamphlets, the Federalist Papers, and Thomas Paine’s Common Sense took money to print and distribute. Putting up yard signs, putting out bumper stickers, putting up billboards, launching a website. Every one of those requires the expenditures of money. I guarantee you every person in this room — if you think about it — disagrees with the proposition that expending money is not speech. Publishing a book is speech, publishing a movie is speech, blogging is speech. Every form of effective speech in our modern society requires the expenditure of money from citizens.

So the campaign against Citizens United — like the campaign for the Sedition Act of 1798 — is not really about whether the freedoms of speech and press are related to money. The real issue may have been revealed in the June 3 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing when Senator Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) observed that “Most of the money that has come from the SuperPacs and many of these groups are knocking out incumbents, particularly those from the other side, whether they be Republican or Democrat.” Schumer’s accidental candor also reveals the changing, self-centered nature of the rhetoric in favor of “campaign finance reform.” For decades, leftist advocates of campaign finance reform have complained that the deck was stacked in favor of incumbents, who have most of the donations and better access to mainstream media. With most of the post-Citizens United independent money opposing incumbents, the playing field has been a little more leveled.

That, too, mirrors debate on the Sedition Act of 1798. Today, the top five left-wing media conglomerates spend more than $600 billion in a two-year election cycle, with their almost blatant support of Democratic candidates, compared with the millions expended by the Koch brothers. Back in 1798, Democratic-Republican Rep. Albert Gallatin of Pennsylvania observed before the House of Representatives of the Sedition Act:

At present, when out of ten presses in the country nine were employed on the side of [Federalist Adams] Administration, such is their want of confidence in the purity of their own views and motives, that they even fear the unequal contest, and require the help of force in order to suppress the limited circulation of the opinions of those who did not approve all their measures.

Photo of Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.): AP Images