The day after he won the Republican primary for U.S. Senate in Kentucky, it was clear that one of the issues political newcomer Rand Paul will have to confront in the general election campaign is his beliefs about a federal law enacted 46 years ago and rarely debated in more recent decades. The law is the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the issue that has been raised anew is its ban on discrimination in public accommodations.

In a recent interview with the Louisville Courier-Journal, Paul said he considered it a "bad business decision to exclude anybody from your restaurant. But at the same time I do believe in private ownership. But I think there should be absolutely no discrimination on anything that gets any public funding and that’s most of what the Civil Rights Act was about to my mind."

That earned Paul a scathing editorial indictment by the paper, and Rachel Maddow Wednesday night grilled the candidate on the issue on her MSNBC show.

"Was the Courier-Journal right?" she asked. "Do you believe that private business people should be able to decide whether they want to serve black people or gays or any other minority group, as they said?"

Paul did not answer that directly, but said repeatedly during the interview that he abhorred racism of any kind. "I don’t think we should have any government racism, any institutional racism," he said. He believes in most of the provisions in the Civil Rights Act, Paul said. "One dealt with private institutions and had I been around, I would have tried to modify that," he said.

Earlier in the day, Paul was questioned on the same subject on National Public Radio by All Things Considered host Robert Siegel.

SIEGEL: “You’ve said that business should have the right to refuse service to anyone, and that the Americans with Disabilities Act, the ADA, was an overreach by the federal government. Would you say the same by extension of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?”

DR. PAUL: “What I’ve always said is that I’m opposed to institutional racism, and I would’ve, had I’ve been alive at the time, I think, had the courage to march with Martin Luther King to overturn institutional racism, and I see no place in our society for institutional racism.”

SIEGEL: “But are you saying that had you been around at the time, you would have — hoped that you would have marched with Martin Luther King but voted with Barry Goldwater against the 1964 Civil Rights Act?”

DR. PAUL: “Well, actually, I think it’s confusing on a lot of cases with what actually was in the civil rights case because, see, a lot of the things that actually were in the bill, I’m in favor of. I’m in favor of everything with regards to ending institutional racism. So I think there’s a lot to be desired in the civil rights. And to tell you the truth, I haven’t really read all through it because it was passed 40 years ago and hadn’t been a real pressing issue in the campaign, on whether we’re going for the Civil Rights Act.”

What is lost in all of this is the reason Goldwater, no racist himself, voted against the Civil Rights Act. He believed, as do many today that the power granted Congress under the Constitution to regulate commerce "among the several States" was meant to permit the free flow of goods and services from state to state and did not extend to private transactions within a state. But by the time of the Civil Rights Act, both the Congress and the Supreme Court had grown accustomed to interpreting the interstate commerce clause broadly enough to cover anything that might in any way "affect" interstate commerce. In one of the early challenges to the 1964 law, a unanimous Supreme Court declared in Katzenbach v. McClung: "Congress has determined for itself that refusals of service to Negroes have imposed burdens both upon the flow and upon the movement of products generally." How so? Simple, the court found. "The fewer customers a restaurant enjoys the less food it sells and consequently the less it buys."

Thus, Congress may regulate what you buy and sell and what you don’t buy and sell. It is reminiscent of the court’s Wickard v. Filburn ruling of 1942, holding that a farmer could be found in violation of the New Deal’s Agriculture Adjustment Act for growing wheat he had consumed on his own land. The farmer believed, logically enough, that if he hadn’t sold the crop then it wasn’t commerce and it certainly wasn’t interstate. But the court held that if he had not grown the wheat he would have had to purchase it and thus his decision to grow contributed to a reduced demand that could negatively affect the price of the crop in interstate commerce. (As Archie Bunker used to say, "Can’t you folly (sic) that?")

In another case that same year, United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., the court ruled that "even if appellee’s activity be local, and though it may not be regarded as commerce, it may still, whatever its nature, be reached by Congress if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce." In short, virtually every activity, "whatever its nature," comes under the interstate commerce clause, even it it’s not interstate and it’s not commerce.

Rand Paul said in his victory speech Tuesday night that the message of the Tea Party movement that supported him is "we’ve come to take our government back." So it is fair to question the candidate about what his vision of limited, constitutional government might entail. But a little perspective is in order. Paul’s comments about the Civil Rights Act appear to have been in response to hypothetical questions put to him by reporters. He may, in fact, regard the Civil Rights Act as congressional "overreach," of which there are many, more recent and flagrant examples. He and his Tea Party followers have been too busy fighting the healthcare overhaul, the financial bailout, and the rapidly escalating federal debt to mount a campaign against the 1964 Civil Rights Act, were they so inclined. And retailers who would, if permitted, turn away customers because of skin color or race would be too few to mention. The experience of nearly half a century has brought home the point that while customers may come in black and white, brown, yellow and red, their money is always green.

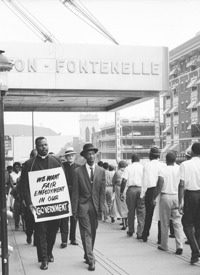

Photo: AP Images