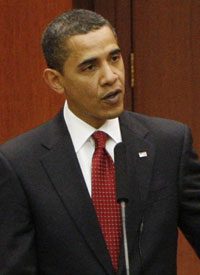

President Barack Obama stated at a press conference in Turkey last week that we Americans “do not consider ourselves a Christian nation, or a Muslim nation, but rather, a nation of citizens who are, uh, bound by a set of values.”

Obama has made similar statements in the past. In June 2007, he told CBS, “Whatever we once were, we are no longer a Christian nation — at least, not just. We are also a Jewish nation, a Muslim nation, a Buddhist nation, and a Hindu nation, and a nation of nonbelievers.” Note the progression. In 2007, he said we are no longer “just” a Christian nation. Now, in 2009, he says we “do not consider ourselves a Christian nation” at all.

There is a sense in which this writer agrees with him. Unlike England at the time of our nation’s founding, we do not have an official state church. And I don’t want one — I don’t want Barack Obama to be the head of the church.

But that’s not what the U.S. Supreme Court meant when, in Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U.S. 437 (1892), they held that “this is a Christian nation.” They meant that this nation was founded on biblical principles, and that those who brought these biblical principles to this land and who implemented those principles in our system of government were for the most part professing Christians who were actively involved with Christian churches. In my own book Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of Our Founding Fathers (Baker Book House, 1987, 2008), I demonstrate that at least 51 of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention were members of Christian churches, and that leading American political figures in the founding era quoted the Bible far more than any other source.

And the ideals on which they framed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution — that man is subject to the laws of nature and of nature’s God, that God created man equal and endowed him with basic unalienable rights, that human nature is sinful and therefore government power must be carefully restrained by the Constitution — are ideals that they derived, directly or indirectly, from the Bible. Some of these ideals may be shared by those of other religious traditions. But the Founding Fathers, with few exceptions, did not read the Koran, or the Upanishads, or the Bagavigita. They read the Bible, and they heard the Bible preached on Sunday mornings.

Besides denying that America is a Christian nation in his April 6 news conference in Turkey, President Obama told the Turkish Parliament on the same day: “We will convey our deep appreciation for the Islamic faith, which has done so much over the centuries to shape the world — including in my own country.” Arguably, this is a true statement — if by his “own country” Obama was referring to Kenya!

But seriously, the suggestion that Islam has shaped America in any substantial way is ludicrous. As Robert Spencer asks,

Were there Muslims along Paul Revere’s ride, or standing next to Patrick Henry when he proclaimed, “Give me liberty or give me death”? Where there Muslims among the framers or signers of the Declaration of Independence, which states that all men — not just Muslims, as Islamic law would have it — are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? Were there Muslims among those who drafted the Constitution and vigorously debated its provisions, or among those who enumerated the Bill of Rights, which guarantees — again in contradiction to the tenets of Islamic law — that there should be no established national religion, and that the freedom of speech should not be infringed?

The primary contact our Founding Fathers had with Islam occurred during their struggles with the Barbary pirates, who from 1500-1800 carried over a million European Christians — including some Americans — into Muslim slavery. For centuries the Knights of Malta protected Europe from the Barbary pirates, but after their demise the European powers decided that paying tribute to the Barbary rulers in exchange for protection was easier and cheaper than fighting them. But this galled the Americans. In 1786, while Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were in Europe, they asked the ambassador from Tripoli by what right Tripoli could claim tribute from nations which had done his country no injury. Jefferson and Adams reported the ambassador’s response:

It was written in their Koran that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet [Mohammed] were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful [Muslims] to plunder and enslave; and that every Muslim who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.

When Jefferson became president in 1801, he refused to pay tribute to the Barbary states, and Tripoli, Algiers, and Tunis declared war on the United States. The American Navy blockaded the coast of North Africa, and American marines stormed “the shores of Tripoli” and captured the city, forcing the Barbary rulers to agree to terms of peace. The Barbary states soon broke the treaty and demanded tribute again, and President James Madison again sent the U.S. Navy to the Mediterranean, forcing the Barbary states to again sign a treaty of peace.

Clearly, Islamic influence on the United States was minimal, and what little influence there was, was mostly negative.

Much of the Muslim world has a negative view of the United States. Sadly, President Obama seems to think the Muslim world will warm up to our country if our president shares their negative view. But the lessons of history clearly demonstrate that the world’s leading super-power is never popular. But to what country do the tired and poor of the world seek to immigrate — Afghanistan? What nation’s constitution do other nations look to as a model — China’s? And when other nations are stricken with disaster, to what nation do they turn for help — Sudan?

No, they temporarily set aside their “Yankee Go Home” placards and turn to America, the most generous nation in the history of the world, for help that is seldom denied. And America’s generosity is a response learned from our Christian heritage.

Photo: AP Images