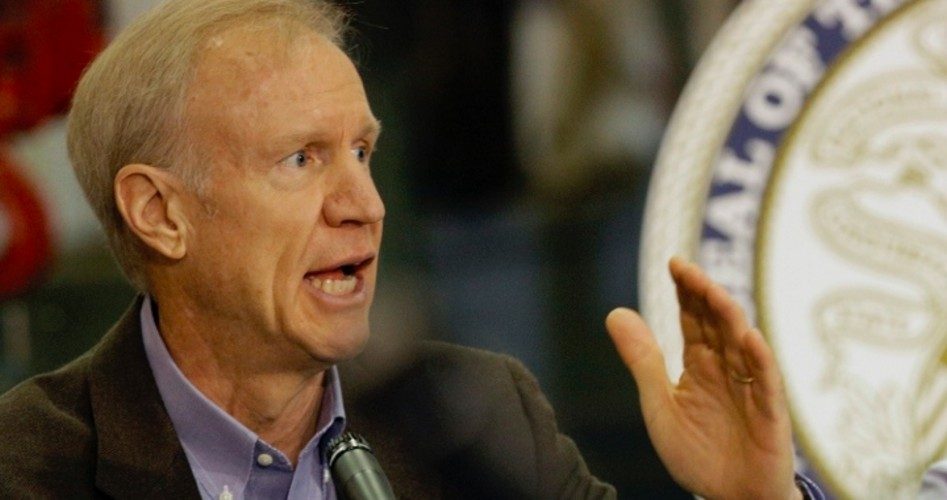

Chicago’s pension contributions to its four dreadfully underfunded pension plans were supposed to double this year to $1.1 billion, up from $478 billion in 2015. But state legislators passed a bill (which had been bottled up for nearly a year) to cut that back to under $900 million. On Friday Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner (shown) vetoed the bill, expressing in no uncertain terms that he was tired of politicians kicking the can down the road:

By deferring responsible funding decisions until 2021 and then extending the timeline for reaching responsible funding levels from 2040 to 2055, Chicago is borrowing against its taxpayers to the tune of $18.6 billion.

This practice has got to stop. If we continue, we’ve learned nothing from our past mistakes.

Those past “mistakes” have got Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel in a pickle. He dares not challenge the unions to cut benefits for teachers and city workers. The state enacted the largest property tax increase in history in 2011, mulcting another $31 billion from taxpayers, nearly all of which went to shore up those pension plans. The pension liabilities, even if funded under the original plan, would still result in the plans running out of money within 10 years. Pension assumptions have just been reduced (slightly), which neatly added $11.5 billion to the city’s $20 billion plan shortfalls. And with stock and bond prices at historic highs, there is little chance that investment returns over the next decade will overcome funding shortfalls through market gains. Already those plans are eating into principal every year just to make payments to current beneficiaries.

And then there’s House Speaker Michael Madigan.

Mayor Emanuel didn’t mention Madigan’s name in his blunt response to Rauner’s veto. Instead, he made it clear that, in order to meet the pension shortfall, Rauner is forcing Emanuel to impose another property tax increase on Chicagoans:

With a stroke of his [veto] pen, Bruce Rauner just told every Chicago taxpayer to take a hike. Bruce Rauner ran for office promising to shake up Springfield [Illinois’ capital city], but all he’s doing is shaking down Chicago residents, forcing an unnecessary $300 million property tax increase on them and using them as pawns in his failed political agenda.

Would that it would be that simple. On May 19 the city’s net pension liability of just one of its four plans, its Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund, jumped by $11.5 billion as the plan’s actuaries were forced to reduce some of its investment assumptions. Those overly generous assumptions have long masked the size of the long-term deficit. Said Richard Ciccarone, the president of Merritt Research Services, which analyzes the finances of cities such as Chicago. “The longer they wait to get this fixed, the more expensive it’s going to get for the city’s taxpayers.”

A year ago that plan had 42 cents in the bank for every dollar of promises it owes in the future. This year it’s down to 32 cents. It is liquidating between 12 and 15 percent of its present assets just to pay out current benefits.

A year ago Governor Rauner spelled out a plan to deal with the state’s suffocating pension plan shortfalls, consisting of cuts in benefits and increases in funding by the city and the plans’ participants. Not only did the bill never make it out of committee, Rauner never even bothered submitting it, knowing that Michael Madigan, the House speaker for 31 of the past 33 years, would bury it in the House Rules Committee, which he controls with the help of his second-in-command, Rep. Barbara Flynn Currie, a Democrat from Chicago.

Madigan, according to Chicago Magazine, was the fourth most powerful Chicago politician in 2012. In 2013 and again in 2014 the magazine moved him up to second position, calling him “the Velvet Hammer — a.k.a., the Real Governor of Illinois.”

For his absolute control over the House, Madigan rated special attention by Austin Berg of the Illinois Policy Institute. After learning how things work there, Berg wrote: “Illinoisans may elect who goes to the House of Representatives, but they don’t choose their representation — at least not in any meaningful sense. [That] power belongs to Madigan. And he represents himself.”

Madigan has no problem gouging taxpayers through raising property taxes because it benefits, handsomely, his company which helps Chicago business owners negotiate lower property-tax bills with the city. If Madigan, per chance, decides to let a bill out of the Rules committee, it is then funneled, according to Berg, to “one of more than 50 committees, each chaired by a lawmaker Madigan picks for the job. Those positions come with stipends worth thousands of dollars each.”

Madigan has no problem with nepotism, either. His son-in-law Jordan Matyas is the chief lobbyist for the Regional Transportation Authority, acting as deputy chief overseeing its Government Affairs Department. His oldest daughter, Lisa, is the attorney general of Illinois.

The only way out of the mess these past “mistakes” have made is through bankruptcy — an option no one is talking about, at least not yet. It would require a bill passed through the House. But bankruptcy would remove Madigan from the equation, requiring all other affected parties (unions, pension plan administrators, taxpayers and bondholders) to come to the bargaining table to deal with the present reality.

The chances of that happening are so small that Chicago now suffers from the worst credit rating of any city in the country, with the exception of pre-bankrupt Detroit. One observer of the ongoing disaster, Mish Shedlock, correctly noted: “Illinois is terminal. [The] cancer is too deep and has spread too far to save the patient. The state is bankrupt morally, politically and monetarily.”

Photo of Gov/ Bruce Rauner: AP Images

A graduate of an Ivy League school and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related article:

Illinois Comptroller: State Is Out of Money; Legislators’ Paychecks Delayed