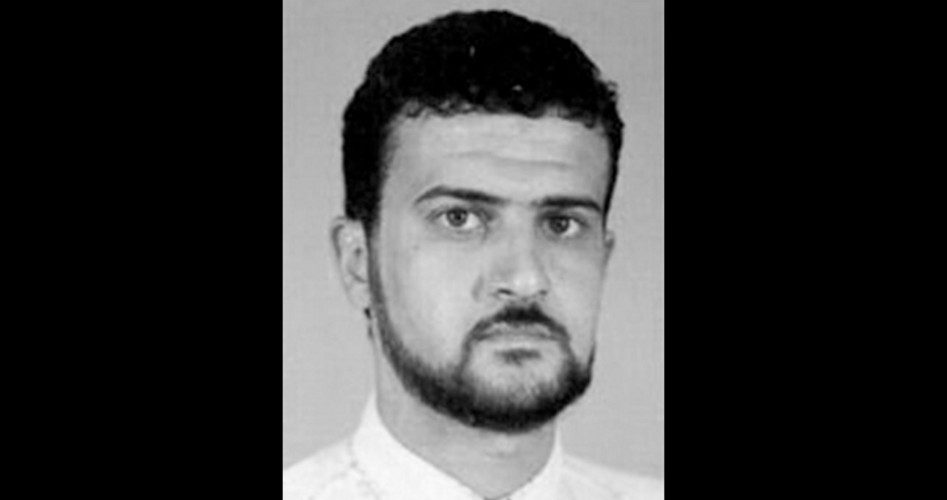

Members of the U.S. Army’s Delta Force captured al-Qaeda leader Nazih Abdul-Hamed al-Ruqai (shown) — known by his alias, Anas al-Libi — in a raid in Tripoli, Libya, on October 5, reported the Indian newspaper the Post. Al-Liby is under indictment in the United States for his alleged role in the August 7, 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, Kenya.

Al-Libi had been on the FBI’s Most Wanted terrorists list since its inception on October 10, 2001. The State Department, through the Rewards for Justice Program, offered up to $5,000,000 for information about Al-Libi’s whereabouts.

On the same day as the raid in Libya, U.S. Navy SEALs carried out a pre-dawn strike against an al-Shabaab militant called “Ikrima,” whose real name is Abdikadar Mohamed Abdikadar, and al-Qaeda terrorists in Somalia. Al-Shabaab (“Party of the Youth”) is a Somalia-based organization with connections to al-Qaeda. On September 21, al-Shabaab took responsibility over Twitter for the Westgate Centre shootings in Nairobi, Kenya, claiming that its militants shot around 100 people in retaliation for the deployment of Kenyan troops in Somalia. However, that operation failed to capture its target.

Secretary of State John Kerry, speaking at the Asia-Pacific economic conference in Bali, Indonesia, said that the raids signaled the ongoing determination of the United States to bring terrorists to justice and sent the message that “members of Al Qaeda and other terrorist organizations literally can run but they can’t hide,” reported Fox News on October 6.

Fox also quoted from a statement released by Pentagon Press Secretary George Little: “On October 5, the Department of Defense, acting under military authorities, conducted an operation to apprehend longtime Al Qaeda member Abu Anas al Libi in Libya. He is currently lawfully detained under the law of war in a secure location outside of Libya. Abu Anas al Libi has been indicted in the Southern District of New York in connection with his alleged role in Al Qaeda’s conspiracy to kill U.S. nationals and to conduct attacks against U.S. interests worldwide, which included Al Qaeda plots to attack U.S. forces stationed in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Somalia, as well as the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, Kenya.”

Al-Libi reportedly is in custody aboard the USS San Antonio, an amphibious transport dock ship in the Mediterranean Sea, and will be transported to New York for prosecution.

A report in Britain’s Daily Mail on October 7 noted that after the 1998 embassy bombings, Al-Libi moved to Manchester, England, where he lived as a student. British police arrested Al-Libi as a terror suspect in 1999, but because he had erased his computer’s hard drive, Scotland Yard detectives could find no evidence to hold him. After he left, in May 2000, anti-terror police raided his flat and found a 180-page handwritten terror instruction book for al-Qaeda followers that was called the Manchester Manual.

The Daily Mail reported that the manual explained how to booby-trap cars and TVs and showed how to kill using a knife. But police found the evidence only after al-Libi had fled the country.

An October 6 report in the Washington Post stated that the capture of al-Libi “was a rare instance of U.S. military involvement in ‘rendition,’ the practice of grabbing terrorism suspects to face trial without an extradition proceeding and long the province of the CIA or the FBI.” The Post report makes no distinction between ordinary rendition, most commonly accomplished by one nation’s handing over of a wanted person to another under an extradition treaty, and “extraordinary” or “irregular” rendition, which may be defined as “the apprehension and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to another.”

The Libyan government issued a statement on October 6 protesting the “kidnapping” of al-Libi, who was born in Libya and is therefore a Libyan citizen. In response to the charges, noted the Post, Secretary of State Kerry described al-Libi as “a key al-Qaeda figure,” who “is a legal and an appropriate target for the U.S. military.”

The military was assisted by agents of the FBI and CIA in apprehending al-Libi.

An AP report carried by ABC News stated the Libyan government had “contacted the American authorities and asked them to present clarifications” regarding the al-Libi apprehension. Libyan officials also expressed hope that the incident would not affect its relationship with the United States.

The report also quoted Secretary of State Kerry’s statement on Monday defending the operation and dismissing complaints about the way it was conducted. Kerry stressed that it was important not to “sympathize” with wanted terrorists.

“I hope the perception is in the world that people who commit acts of terror and who have been appropriately indicted by courts of law, by the legal process, will know that United States of America is going to do anything in its power that is legal and appropriate in order to enforce the law and to protect our security,” Kerry told reporters on the sidelines of the economic conference in Bali.

A report in the Irish Times quoted a statement from Western-backed Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan, who said: “The Libyan government is following the news of the kidnapping of a Libyan citizen who is wanted by US authorities.”

“The Libyan government has contacted U.S. authorities to ask them to provide an explanation.”

The question of the legality (and constitutionality) of the U.S. raid to capture al-Libi is more subjective than the use of U.S. forces in overseas military operations that rise to the level of out-and-out wars. The Constitution is quite clear in that power is granted only to Congress “To declare War, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.”

Presidents have taken liberties over the past 63 years to go to war without a congressional declaration of war. (The last time Congress declared war was in 1942, against Axis partners Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania.)

One might be tempted to cite as precedent for the recent raid on Tripoli the First Barbary War between the United States and the Barbary States, one of which was Tripoli (the same “shores of Tripoli” mentioned in the Marine Corps hymn). While not issuing a formal declaration of war, Congress on February 6, 1802 authorized the arming of merchant ships to ward off attacks.

When the problem with Barbary pirates still was not eliminated, Congress on March 3, 1815, authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers in the Second Barbary War. The war brought an end to the American practice of paying tribute to the pirate states.

Moving forward to the 21st-century War on Terror, it is difficult to find precedent for such a war, though protection of U.S. interests (both overseas and domestic) is clearly constitutionally justified. The Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed as S.J. Res. 23 by Congress on September 14, 2001, authorizes the use of U.S. armed forces against those responsible for the attacks of September 11, 2001. The authorization granted the president the authority to use all “necessary and appropriate force” against those whom he determined “planned, authorized, committed or aided” the September 11 attacks, or who harbored said persons or groups.

Does the AUMF serve as a blank warrant to apprehend those such as Anas al-Libi? That would be an outrageous stretch; even an occasional good end would not justify such an open-ended means, which, invariably would lead from one dangerous abuse to the next. The crimes of which al-Libi is charged were committed in 1998, before the AUMF was passed. Would not the use of a law passed in 2001 to prosecute a crime committed in 1998 constitute ex post facto law, which the Constitution prohibits?

Since U.S. embassies constitute U.S. territory abroad, an attack on them is as certainly as egregious an offense as the attack on (for example) Pearl Harbor. Retaliation and apprehension of the offending parties is, therefore, clearly justifiable. The only questions that remain are: How, and in what manner, should the perpetrators be brought to justice? Is congressional authorization required? Absolutely, otherwise a president of the United States has plenary power to designate whomever he will as an “enemy” of the United States. Is permission from the government of the nation where the offenders are apprehended also required? Normally, yes — with a “friendly” country with which we have formal diplomatic relations. Invasion of a sovereign nation to kill or apprehend an alleged criminal against that nation’s will is universally considered an act of war and the authors of our Constitution did not propose empowering the president to drag this nation into war on a personal whim. Even violating an antagonistic country for a justifiable end could result in an escalation leading to calamitous consequences. The president, whoever he may be, and regardless of his party affiliation, must know that Congress and the American people will hold him to account for any abuses or usurpations of executive authority in this area.

Whether criminals are foreign or domestic, and whether the crimes are committed in the United States or abroad, the best guide to justice remains the Constitution, even though applying it to some of the murkier situations in U.S. foreign policy, admittedly, remains a challenge that might test the wisdom of Solomon.